On 24 June 2022, Berlin’s mayor Franziska Giffey had a “completely normal conversation” with Kyiv’s mayor Vitali Klitschko.

Or so she thought.

-

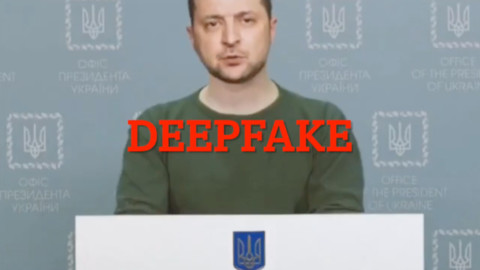

Volodomyr Zelensky telling Ukranian troops to surrender — or not. Another ‘deep fake’ (Photo: Twitter)

She started to become suspicious when the supposed mayor asked her to support for a gay pride parade in the middle of war-torn Kyiv.

It was not Klitschko, it turned out, but an impostor. Giffey’s office later said the person was probably using deepfake technology to trick Berlin’s mayor (though the tech behind it has remained unclear).

A year or two ago, few were familiar with deepfakes; today most people are. Its popularity is in large part due to its prominence on popular apps, such as face-swaps or AI-powered lip-syncing tech on TikTok.

Once merely a tool for entertainment, disinformation actors have become begun to leverage them. This year, 2022, alone saw multiple similar high-profile stunts, from those that were relatively speaking less harmful — such as the scam on JK Rowling — to potentially dangerous ones, like the deepfake imitating Ukrainian president Vladimir Zelensky instructing his citizens to lay down their arms.

But what’s scarier is that deepfakes are themselves rapidly becoming an ‘old-fashioned’ way to create fake video content.

The new kid on the block this year is fully-synthetic media. Unlike deepfakes, which are partially synthetic and graft the image of one person’s face onto the body of another’s in an existing video, fully synthetic media can be created seemingly out of thin air.

This year saw the rise of text-to-image software that does exactly that.

It’s not actual magic, but the technology behind the generators is hardly less mystifying. The models powering text-to-image software rely on machine learning and vast artificial neural networks that mimic your brain’s natural neural networks and their ability to learn and recognise patterns. The models are trained to recognise millions of images paired and their text descriptions.

The user need only enter a simple text prompt and — hey presto! — out comes the picture. The most popular programs are Stable Diffusion and DALL-E — and both are now free of cost and available open access.

This points to troubling potential: these tools are a dream for a disinformation actor who need only to be able to imagine the ‘evidence’ they need to support their narrative, and then create it.

These technologies are already starting to penetrate social media and images are only the beginning.

Just recently in September, Meta released ‘Make-A-Video’ that enables users to create “brief, high-quality video clips” from a text prompt. Experts warn that synthetic video is even more troubling than synthetic images, given that today’s social media landscape already favours fast and clipped videos, over text or images.

Entertainment aside, the penetration of synthetic media onto an app like TikTok is particularly troubling. TikTok is centered on user-generated content, encouraging people to take existing media, add their own edits, and re-upload — an operating model not too different from deepfake creation.

Recent research by the Associated Press has shown that one-in-five videos on TikTok are misinformation and that young people increasingly use the app as a search engine on important issues like Covid-19, climate change, or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It is also significantly harder to audit than other apps like Twitter.

In short, the TikTok app is a perfect incubator for such new tactics, which then commonly spread across the web through cross-platform sharing.

Most disinformation is still created using commonplace tactics like video and sound-editing software. Altering videos by splicing, changing the speed, replacing the audio, or simply taking the video out of context, disinformation actors can already easily sow discourse.

Seeing is still believing

Yet, the danger of text-to-image is already real and present. One does not have to expend too much creative energy to imagine the not-too-distant future when untraceable synthetic media appears en masse on our phones and laptops. As trust in institutions and reliable media is already tenuous, the potential impact on our democracies is terrifying to contemplate.

The sheer density of news today is a compounding part of the problem. Each of us only has a finite capacity to consume news — let alone fact-check it. We know that debunking is a slow and ineffective solution. For many of us, seeing is still believing.

We need to provide an easy and widespread solution to empower users to identify and understand false images or videos immediately. Solutions that do not empower users — and journalists — to identify fake news faster, easier, and more independently will always be a step behind.

Currently, the most promising solutions focus on provenance: technology which embeds media with a signature or invisible watermark at the point of creation, as proposed by Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative. It is a promising but complex solution that requires collaboration across multiple industries. Policymakers, especially in Europe, should give it more attention.

We live in a fast-paced world and disinformation moves faster than our current solutions. It’s time we catch up.