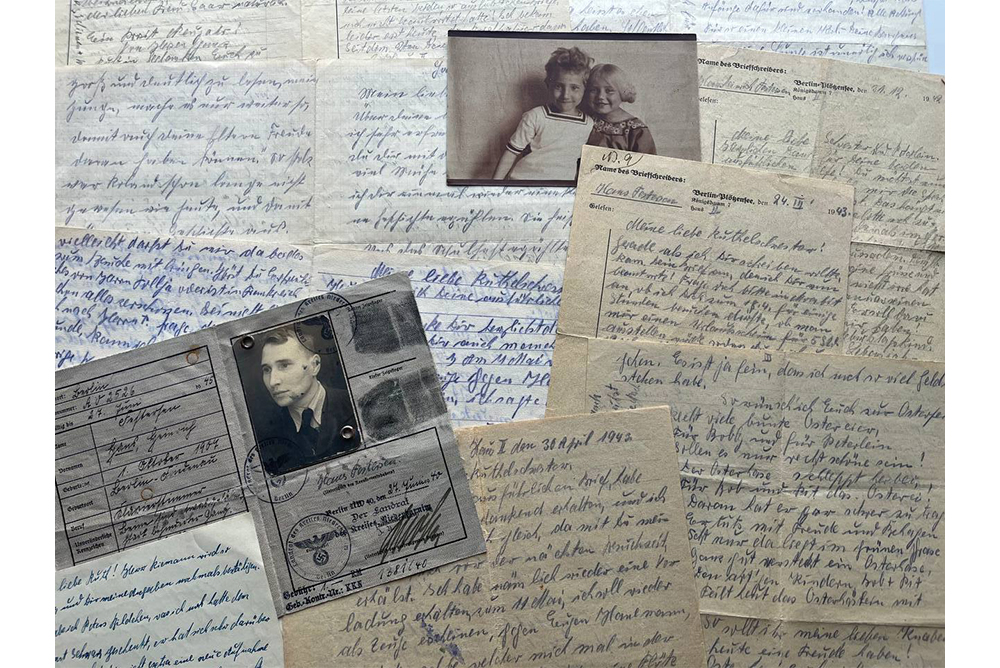

Hans Heinrich Festersen was a gay, disabled man hanged by the Nazis. A compilation of documents and photographs—part of the “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” exhibit curated by the author—illuminates his story. Courtesy of the Schwules Museum.

On September 8, 1943, Hans Heinrich Festersen was hanged at Berlin’s Plötzensee prison. Festersen, 35, had been arrested almost a year earlier, on October 12, 1942, for violating Paragraph 175, the German law prohibiting sex between men. He received his death sentence on July 13, 1943.

Though the Nazis had broadened the law and increased its severity, gay men were not usually killed for violating Paragraph 175. So, why was Hans Festersen killed, and how did his letters from prison to his sister Ruth Marie end up in a museum exhibit in Berlin today?

From January 1940 until August 1941, German “health courts” deemed 70,000 disabled persons to be “unworthy of life.” They were murdered in gas chambers as part of the Aktion T4 program. After the program officially ended and until the end of the war, 230,000 more people with disabilities, including infants, were killed by gas and other means, including starvation, medication overdose, and neglect.

Letter from Hans Heinrich Festersen to his sister, written at Plötzensee prison, December 14, 1942. Photo courtesy of the Schwules Museum.

Festersen, the son of noted ceramicist Friedrich Festersen, was physically disabled due to cerebral palsy. He used walking aids to get around. The police arrested him along with three other gay disabled men who had been living with Festersen at a Protestant institution for the unemployed and homeless.

Crucial to the case against the four men was the 1933 “Law Against Dangerous Habitual Criminals,” which allowed indefinite imprisonment and castration of sex offenders. But according to the memorial site at Plötzensee, by 1943 “wartime criminal laws allowed for death sentences for almost any criminal offense.”

The four gay disabled men’s trial records, as historian Andreas Pretzel reports, are filled with biases against, and misrepresentations of, both disability and being gay. The court’s judgment described Festersen and his co-defendants as being “mentally weak” and “not fully sane.” Their sexuality was deemed “unnatural fornication.” Pretzel concludes that their “death sentences were aimed at the destruction of life allegedly unworthy of life.” The phrase “life unworthy of life” was the term the Nazis used when deciding which of the disabled would be killed.

Ultimately, does it matter if Hans Heinrich Festersen was killed because he was gay or because he was disabled or because he was caught up in what the Plötzensee memorial site calls “a reign of judicial terror”?

I know firsthand the challenges of interpreting a life at the intersection of identities—I am both gay and disabled. I’ve written three books with my intersectionality as a focus. I’m also Jewish. Now, living in Berlin, I’ve too often been asked which of my identities is the “most difficult.”

I’m deeply interested in Hans Festersen’s story, which is at the center of “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer,” the exhibit I curated on queer/disability history, activism, and culture, at the Schwules Museum in Berlin through January 30, 2023.

Ultimately, does it matter if Hans Heinrich Festersen was killed because he was gay or because he was disabled or because he was caught up in what the Plötzensee memorial site calls “a reign of judicial terror”?

Disability arts and culture scholar Carrie Sandahl coined the phrase on which the exhibit’s title is based in a 2003 essay. “[S]exual minorities and people with disabilities,” she writes, “share a history of injustice: both have been pathologized by medicine; demonized by religion; discriminated against in housing, employment, and education; stereotyped in representation; victimized by hate groups; and isolated socially, often in their families of origin.”

Queer history and disability history, though similar, were not quite parallel. However, with the advent of eugenics, from the late 19th century into the 20th, these histories more often ran together, culminating most dangerously during the Nazi regime in Germany.

It’s relatively easy to find information on the fates of Jewish people with disabilities under the Nazi Reich. But researching the history of those killed who were both queer and disabled is far more difficult. When I asked Petra Fuchs, an expert on Aktion T4 who worked on the T4 Memorial and Information Center for the Victims of the Nazi “Euthanasia” Program in Berlin, if she knew of any, she asked if I had found anyone.

So it was quite a surprise when Birgit Bosold, my co-curator and member of the board of directors at the Schwules Museum, shared with me a 2008 local newspaper article about a commemoration of the murders of Hans Festersen and the men arrested with him. The article alluded to the men being disabled, though it mainly focused on their sexuality and their life at the Protestant institution.

It was even more surprising when, a few weeks later, Birgit informed me that five letters Festersen wrote to his sister from Plötzensee were in the museum archive. In these intimate letters, Festersen talks about his future, wanting to end his “wandering around in institutions” by marrying a “slightly disabled classmate,” whom he calls “Miss Hanna.” In his last letter in the archive, dated May 22, 1943, he wonders if he’ll be sent for sterilization. His letters included rhymed poems for his young nephew, Peter, who, decades later, donated the letters to the museum.

Clearly, amid the most difficult circumstances, Festersen kept his humanity. And when we remember the history—the lives—of those who were both queer and disabled, we humanize those who are too often looked upon as doubly “other,” or whose intersectionality is not recognized or understood.

Many (most?) of us live at the intersection of more than one identity. Exploring the connections between our multiple identities provides a deeper understanding of how our intersectional lives are lived, as well as perceived.