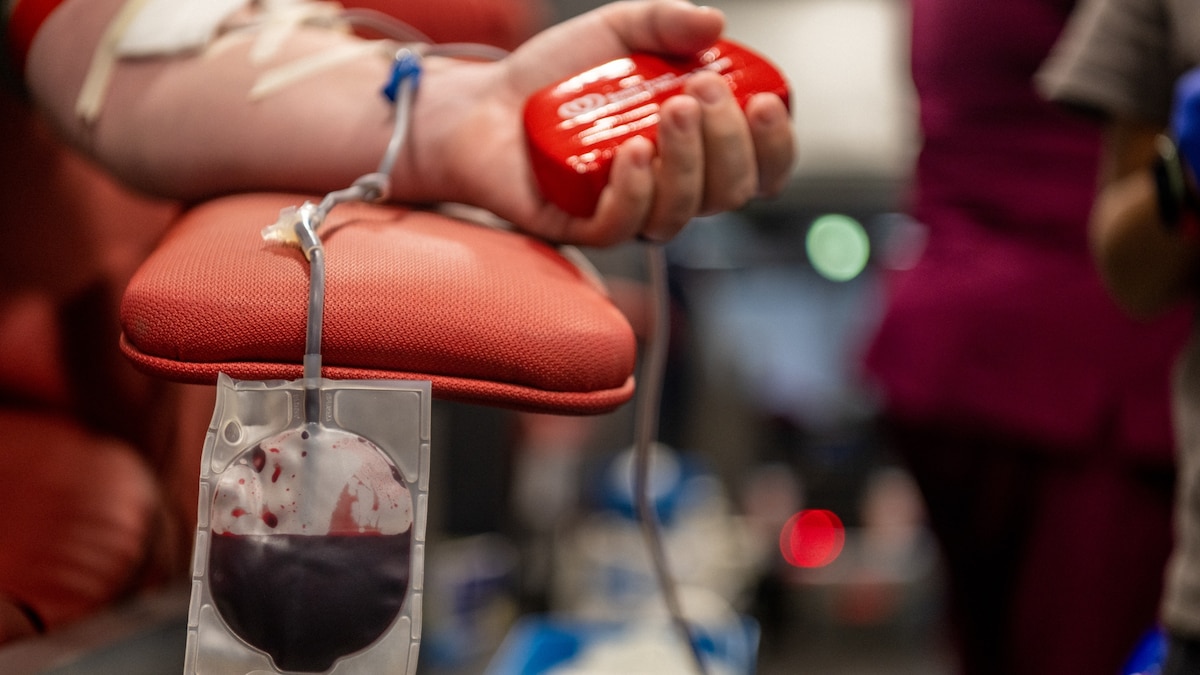

Lukas Pietrzak first donated blood in 2013, when he was a high school student. The cause mattered to him because two units of donated blood had kept this father alive in the immediate aftermath of a cycling accident. They shared the same blood type, and if anything were to happen to his father again or to someone else, he wanted the chance to save their life too. But when Pietrzak participated in another blood donation drive later that same school year, it would be his last.

Sitting in the waiting room of a blood donation center in 2014 in Virginia Beach, where he grew up, Pietrzak remembers checking yes to a question on a form asking if he’d ever had sexual contact with another man. “I’d been exploring my sexuality—as people do in high school—and I’d had an encounter with another man,” he says. A clinician reviewed his form and told Pietrzak that he wasn’t eligible to donate blood anymore. Under U.S. Food and Drug Administration rules at the time, gay and bisexual men were barred from donating blood—a policy that had been in effect since the 1980s. “It felt as though our blood was dirty, as though it wasn’t good enough to help save a life.”

For years, activists and scientists have been advocating for revised blood donation rules linked to HIV transmission concerns and the FDA is now looking into relaxing these restrictions.

In 2015, the federal agency updated its policy to allow gay and bisexual men to donate blood, but only if they hadn’t had sex with another man for at least a year. In 2020, amid major blood shortages in the pandemic, the federal agency shortened that period to three months.

Scientists like Monica Hahn, an HIV specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, have argued that these policies are discriminatory, antiquated, and not based in science “to the point that there is absolutely no medical reason anymore to have this ban or waiting period,” she says. Our ability to screen blood samples for HIV has really been revolutionized, she says.

Over the years, Pietrzak grew resentful of the FDA rules. “They were excluding a group of otherwise eligible volunteers who wanted to give blood and basically saying because of who you are and who you’re with, we don’t want your blood,” he says.

So he participated in an FDA-funded study that commenced last year and considers whether donors could be assessed based on their individual HIV risks rather than sexual identity. “I’m hopeful this is a step toward an equitable blood donation policy,” Pietrzak says.

What prompted the blood donation restrictions?

In the early 1980s, gay and bisexual men were one of the highly affected groups during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded thousands of cases where HIV was transmitted via blood transfusion. Hence, in 1985 the FDA prohibited blood donations from men who have sex with other men because the virus had not been fully characterized, there were no effective treatments, the diagnostics technology had limitations, and blood testing wasn’t widely available.

First-generation HIV tests came to market in the mid-1980s. But these tests could not detect the virus until 10 weeks after infection. “If somebody acquired HIV, it would be several months before their blood test would come out positive,” Hahn says. But along with these limitations, homophobia also fueled the debate on who could or couldn’t donate blood.

Over the years, the lag time between exposure to the virus and tests detecting its presence in the bloodstream declined. “The HIV testing we have today is light years ahead of the testing we had available in the 1980s and 1990s,” Hahn says.

While tests that detect antibodies against HIV still have a 23- to 90-day window, nucleic acid tests that detect genetic material of the virus can spot HIV 10 to 33 days after exposure. The CDC requires all donated blood samples to be screened for antibodies against HIV as well viral genetic material.

Despite these checks, the FDA, in 2015, decided to allow blood donation from only those gay and bisexual men who had abstained from sex with men for one year. The Whitman-Walker Institute in Washington, D.C. has been advocating for a change in the blood donation policy for years. “Our argument was that the window period is not one year but a lot shorter,” says Daniel Bruner, a senior policy counsel at the organization. Also, “not everyone, just because of their identity as a gay man or bisexual, is engaging in sexual activity that poses a risk of HIV,” he says. The rule, for instance, doesn’t exclude monogamous gay men, those who practice safe sex, or test negative for HIV.

And even though the federal agency cut the no-sex-with-another-man window to three months in 2020—as the nation experienced a severe blood shortage crisis—it’s still restrictive, says Keith Sigel, an infectious diseases specialist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York City. In April 2020, more than 500 medical and health professionals sent an open letter to the FDA stating that even the new prohibition period did not go far enough in reversing the unscientific ban.

Last year, the agency funded a study to determine if a questionnaire could be used as an alternative to determine individual risks of HIV among gay and bisexual men wanting to donate blood as opposed to a blanket time-based policy. Other countries, including Canada, France, and Greece, now use similar questionnaire-based risk assessments to determine eligibility.

ADVANCE study

For the so-called ADVANCE study, nearly 2,000 gay and bisexual men in eight cities volunteered to donate blood samples that were screened for HIV and answered questions about their sexual activity. These men between the ages of 18 and 39 were asked about the number of sex partners they’d had in the last month, three months, and 12 months, if they engaged in oral or anal sex, and whether they used a condom or dental dam, for instance.

The idea is to match these answers with the HIV test outcome and ultimately determine what specific parameters could indicate a high HIV risk individual.

The scientists will also be screening the blood samples for PrEP or medicines used prophylactically to prevent an HIV infection, because the drugs can mask virus detection, Sigel says.

Pietrzak, who uses PrEP daily, participated in the study and is hoping the results could help change the blood donation ban. “I understand,” he acknowledges “we have to balance science and blood safety.”