On a sweltering July night in 1925, Henry Gerber—a German-born post-office worker living in Chicago—heard a pounding at his door. Several uniformed police officers shoved their way inside, confiscated his diaries and personal files, and arrested him. Only at the police station, when Gerber saw two of his gay and bisexual friends sitting for mugshots, did he start to realize what was going on: He was being persecuted for launching what was likely America’s first gay-rights organization.

In an article he wrote for a gay magazine in 1962, Gerber likened the next few days to an “Unholy Inquisition.” After police discovered the existence of his group—the innocuously named Society for Human Rights—Gerber spent five days in jail before being released on bail. Although he was never charged, he was fired from the post office. Many of his gay acquaintances refused to be seen with him, fearing undue attention.

If we visualize the history of the gay-rights movement in the U.S. as a scatterplot, Gerber’s Society for Human Rights is an outlier dot, a lone outburst of activism that arrived nearly three decades ahead of its time. Traditional accounts of U.S. queer history tend to begin in the 1950s, when organizations such as the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis ushered in the first, tentative era of activism. Then, the story goes, the 1969 Stonewall riots unleashed the movement’s more radical, liberationist phase. The Society for Human Rights, which existed for less than a year, from 1924 to 1925, and which aimed to create a political constituency around gay rights, is often reduced to a footnote. But the existence of Gerber’s organization complicates things: If queer people were organizing themselves in the 1920s, what happened to the movement in the 30 years or so in between?

In An Angel in Sodom: Henry Gerber and the Birth of the Gay Rights Movement, Jim Elledge, a veteran chronicler of gay Chicago, makes the case that we should consider Gerber not an asterisk, but a forefather of the gay-rights movement—one who would influence later generations of activists. In telling Gerber’s story, An Angel in Sodom offers a rare glimpse into a 1920s and ’30s queer world about which we still know precious little. After Gerber, the movement didn’t disappear—it just went underground.

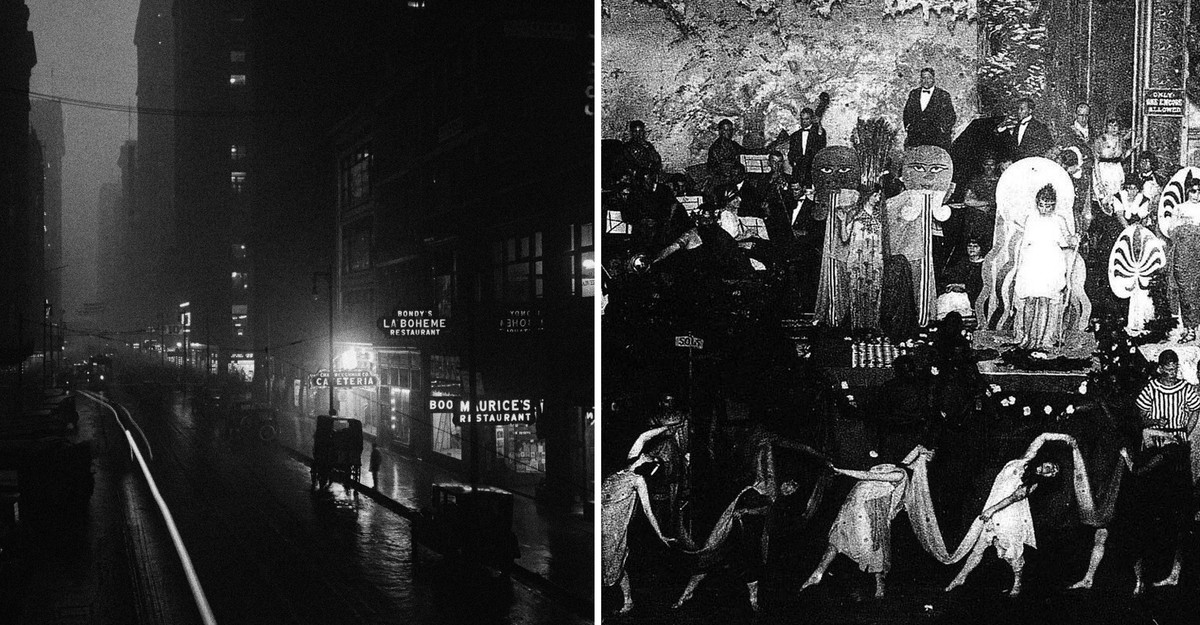

Born in Passau, Germany, in 1892, Henry Gerber first arrived in Chicago at the age of 21 with his younger sister. There, he found a hidden but vibrant gay scene that spanned saloons, vaudeville shows, and street corners in the city’s Towertown neighborhood. A chagrined city investigator once estimated that “twenty thousand active homosexuals” lived in Chicago. Anyone could enter their world, if they only knew where to look.

The police were active too. Gerber was arrested for having sex with men, and around the time the U.S. entered World War I, he was committed to an insane asylum. In 1919, Gerber, who had up until then gone mostly by his birth name, Josef Dittmar, unofficially changed his name in order to hide his medical history. He enlisted in the Army and was dispatched to Koblenz, Germany, to work as a proofreader for a military newspaper. There, Gerber found one of the world’s most open and progressive gay scenes. He was particularly inspired by the Institute of Sexual Science, a research organization headed by the renowned sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, who gave trans people formal ID cards that helped them avoid arrest for cross-dressing.

Gerber returned to Chicago in 1923, buoyed by a newfound understanding of what gay activism could look like. “Unlike Germany, where the homosexual was partially organized,” Gerber wrote in 1962, “the United States was in a condition of chaos and misunderstanding concerning its sex laws.”

He soon came up with the idea of forming an advocacy group that would push for an end to sodomy laws and other forms of legal discrimination—the beginnings, he thought, of an informal gay-rights movement. Most of his friends dismissed the plan as “rash and futile,” Gerber remembered in his 1962 article. It was certainly a gamble. At that point, few gay men and lesbians conceived of themselves as being part of a minority group, with their own distinct set of interests and civil-rights needs.

But Gerber thought that gay people, especially gay men, if they worked together, could become a political force of their own. He met John T. Graves, a 46-year-old Black minister who embraced the idea of a society for homosexuals; when the group they founded first met, in late 1924, Gerber named it the Society for Human Rights, and Graves became the president. At least 9 men were identified as early members of the organization.

Records of the Society for Human Rights have been lost or destroyed, but Gerber later described one of the society’s aims as winning “the confidence and assistance of legal authorities and legislators.” The group set out to roll back sodomy laws, hoping to save others like them “the futility and folly of long prison terms for those committing homosexual acts.” Equally radical was what Gerber did after the first meeting: He registered his organization with the state of Illinois. He disguised its mission in coded language (“to promote and to protect the interests of people who by reasons of mental and physical abnormalities are abused and hindered in the legal pursuit of happiness”), and the state formally incorporated it on December 10, 1924—making the Society for Human Rights the first gay-rights organization registered by a state in U.S. history.

The group collapsed after Gerber’s arrest in July 1925. A postal inspector had threatened him with “heavy prison sentences for infecting God’s own country” with his supposed perversions, and Gerber worried that if he continued to draw too much attention to himself, the police would come after him. The sudden fall of Gerber’s group was a warning to any gay people considering political organizing: It wasn’t worth it. Openly identifying as homosexual, and especially as an activist, meant both social ostracism and a likely ticket to jail. For decades, no one, as far as historians know, dared to replicate what Gerber had attempted.

But unbeknownst to the public, Gerber never gave up his vision. Instead, he was careful to hide his work. Around 1930, he took over a pen-pal club, Contacts, and advertised it in winking terms that he hoped would attract gay subscribers. The club, he wrote in one ad, was “an unusual correspondence club for unusual people.” Contacts became a meeting ground for gay men, hidden in plain sight. Although Gerber dropped his explicitly political goals, he believed that building ways for gay people to locate one another was an important step toward creating community.

In tracking Gerber’s life throughout the 1930s and ’40s, Elledge offers tantalizing glimpses of a much larger, underexplored world. He makes reference to A Scarlet Pansy (1932)—a novel by the author Robert Scully, with whom Gerber was friends—and to Chanticleer, a small self-published magazine Gerber worked on in the 1930s that focused on politics broadly, but that still managed to slip in the occasional discussion of homosexuality through articles such as “A Heterosexual Looks at Homosexuality.” Most intriguing, several gay friends of Gerber’s established a New York chapter of the American Rocket Society, an organization ostensibly for space aficionados that Gerber’s associates wanted to turn into a gay social group. These men hoped “the rocket society would afford the club decorum and decency, camouflaging its gay membership,” Elledge writes.

Gerber’s shift from openly advocating for gay rights to covertly bringing together gay people suggests that his ideas never fully died. Even in the 1930s, an era ostensibly without a gay movement, queer people found one another through coded clubs and magazines. Gerber stopped talking about gay people as a political group, but he continued to find ways to help them see themselves as a group, period, with a shared set of interests and goals. That sense of collective identity would become foundational to the struggle we know today.

In the late 1920s, a 17-year-old Los Angeles resident named Harry Hay met a man who identified himself as a “friend of Henry Gerber in Chicago” and told Hay about the Society for Human Rights. The “idea of gay people getting together at all, in more than a daisy chain, was an eye-opener,” Hay wrote later. The concept stuck with him. In 1950, Hay created the Mattachine Society, a secretive group that called for an end to sodomy laws and police entrapment—thereby helping to kick-start the modern queer movement.

But although Gerber’s Society for Human Rights provided the ideological scaffolding for the gay activism of the Cold War generation, Gerber himself slipped into obscurity. When he died on December 31, 1972, at the age of 80, few of the era’s gay activists noticed.

Elledge makes a compelling case for calling Gerber the father of the gay-rights movement. But he can be presented as such only because of a lucky fluke—one of Gerber’s longtime friends and pen pals, a man named Manuel boyFrank, saved the letters the two exchanged. We don’t have such extensive written records for many other queer figures of the era, even though there were surely other people who brought gay and trans people into underground communities. (In the memoir The Female-Impersonators, the pseudonymous writer Jennie June, for instance, references a trans-advocacy group called the Cercle Hermaphroditos, which was active as early as 1895. A Black man named William Dorsey Swann, meanwhile, organized popular drag balls in Washington, D.C., in the 1880s and ’90s.) One wonders what other groups might have been out there—perhaps even more coded and camouflaged than Gerber’s, afraid to put their work down on paper for fear that it could lead to their arrest. These early glimmers of organizing matter because they allow us to see collective queer identity not as something that sprung up out of nowhere in recent decades, but as a long quest that had to be nurtured and fought for—both in and out of the public eye.