We’re making our way through a massive collection of Rocky Mountain News photos that are now in the Denver Public Library’s archives. We polled our readers about which letter “C” subject file we should explore, and you voted for the “Court Jester,” a gay bar that once stood on Court Street downtown. (If you want to get in on the next round of voting, sign up for our newsletter!)

There is not a lot of public information about the Jester. A short passage from a 1981 issue of OUT FRONT says it opened in 1963, was one of the oldest gay bars in town and was demolished that year. The DPL folder just has one image of it: a black-and-white shot of its whimsical facade.

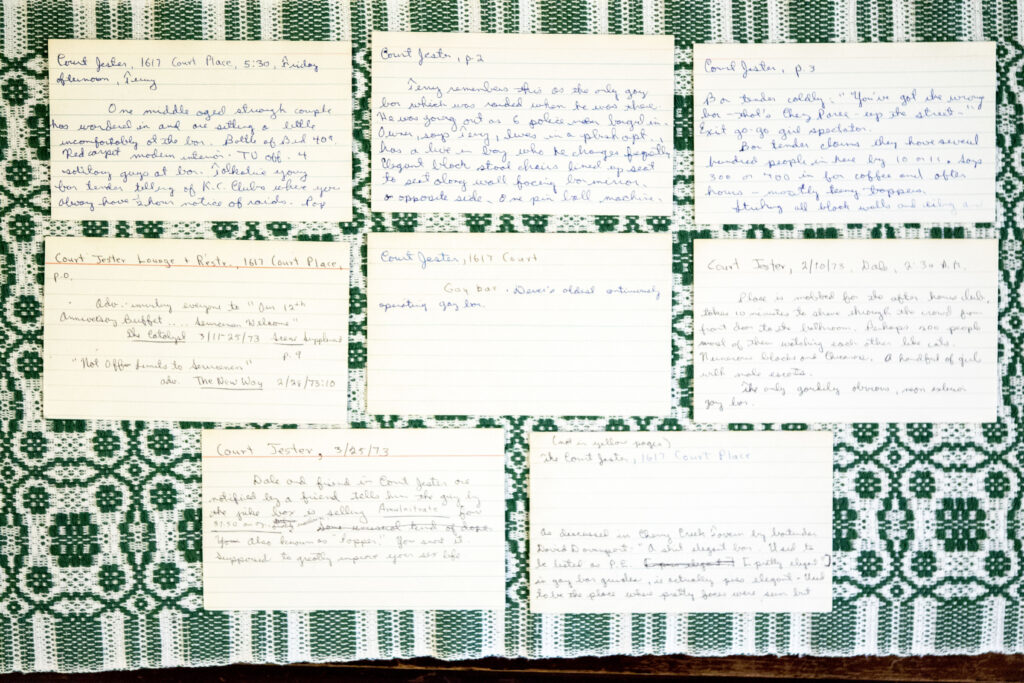

Luckily, local historian Tom Noel, AKA “Dr. Colorado,” did his dissertation on Denver bars and has shoeboxes full of notes from nights out on the town. He visited the Jester in the early 70s as he worked on a scholarly report about gay subculture.

“Large bar. Relief jesters decorating walls. Small dance floor. In back, a bar for wealthy and professional people, and some politicians, allegedly,” he read from an index card he extracted from his collection. “Talkative young bartender tells of Kansas City clubs, where you always had half hour notice of raids.”

Raids, as in: police raids.

As Coloradans have processed the recent mass shooting at Club Q in Colorado Springs, there’s been a lot of talk about how bars opened by and for LGBTQ+ residents have acted as safe spaces in a world that didn’t always embrace their patrons. But being in bars through most of the 20th century could still be dangerous.

“Lewdness and indecency” – in both private and public places – and “crossdressing” were illegal across the U.S. (see page 15). Police officers sometimes busted into bars, arrested people dancing or kissing then carted them off to jail. Other times, they’d enter quietly and entrap people looking for a hookup. That was true in Denver, and at the Jester, until a pivotal 1973 City Council meeting when the community made clear they would not be targeted any more.

It may not be obvious from the old photo, but the Court Jester’s sign was a unique transgression in its time.

“2:30 a.m. in ’73 with a friend of mine, Dale. Place is mobbed for the after-hours club. Takes ten minutes to shove through the crowd from the front door to the bathroom. Perhaps 200 people, most of them watching each other like cats. Numerous Blacks and Chicanos. A handful of girls with male escorts,” Noel read from an index card. “The only gaudily obvious neon-exterior gay bar.”

Then, breaking from his scrawled handwriting, he added: “Most of them would keep a low profile, because they didn’t want walk-in or accidental patrons. But the Court Jester had that pretty blatant sign, which I guess would mean something.”

What it meant, Center on Colfax historian David Duffield told us, was unprecedented exposure.

“Would it be risky to be there, given the sign?” he said. “Yeah, probably, when you look at the edifice of other gay bars within maybe five to ten blocks of that area.”

While sexual “crimes against nature” were against the law as early as the 1600s in colonial America (see page 5), Duffield said the nation found new interest in banning homosexuality 200 years later. Denver added anti-gay laws to its books as early as the 1880s, just a few decades after the city’s founding. It began alongside a “crackdown” on sex workers, who were active in the area known today as LoDo, and as a general reaction to women’s suffrage and rights movements that blossomed at the end of that century.

“It was not so much an extreme moral panic as a more gradual crisis emerging from the expanding roles of women in the 19th century,” Duffield told us. “As more states start to pass anti-crossdressing laws, more states also start to pass suffrage.”

In the 40s and 50s, the start of the Cold War and Joseph McCarthy’s inquisition into people’s personal lives marked another surge in anti-LBGT policy.

This legacy didn’t leave a lot of room for openly gay-friendly establishments in Denver. By the late 1960s, Duffield said, somewhere between three and eight existed in town. That number grew into the 1970s, after the 1965 flood ravaged parts of downtown and businesses moved out of the city’s center.

“It became less desirable, so there was less scrutiny. They needed tenants, so they really didn’t care who you are, what you did, so long as you paid your rent,” he said.

Duffield estimated Denver had about 13 of these bars by the time Noel visited the Jester in 1973. Most were out of the way and hard to pick out from the street, hidden behind darkened windows and nondescript storefronts. Others, like the Brown Palace’s Ship Tavern, became secret pickup spots, quietly recognized by the LGBTQ+ community but never explicitly a “gay bar.”

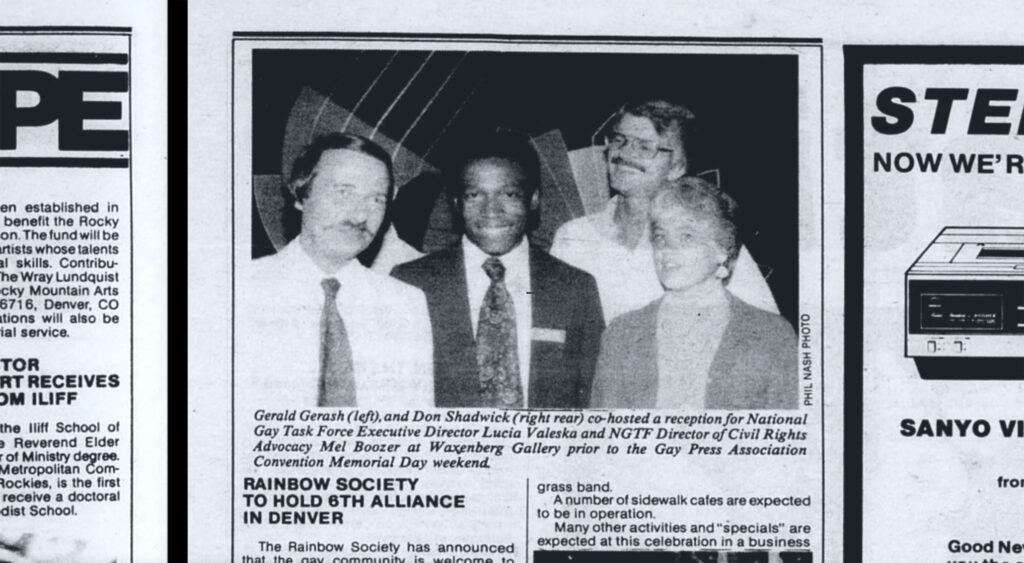

The Court Jester’s stark visibility made it different. Gerald Gerash, a lawyer who specializes in civil rights and helped found the Center on Colfax, told us how that manifested inside.

“I was there, and what I remember is sometimes the bar manager would announce over the loudspeaker that there’s Vice in the bar,” he recalled. “He made it very clear … be careful. Don’t touch anyone. Don’t give them any excuse to arrest you.”

Noel said Terry Mangan, a gay rights activist and historian who first brought him to the Jester, was present for one of those raids.

“Magnan remembers this as the only gay bar which was raided when he was in there,” Noel read from his notes. “He was going out as six cops barged in.”

Activists fought these police raids, eventually marching into City Council chambers to demand change.

While bars were important places to foster Denver’s LGBTQ+ community, it could be dangerous to organize politically inside them.

In 1950, gay rights activists in Los Angeles founded the Mattachine Society, which aimed to present their struggle as a parallel to America’s ongoing civil rights movement. A chapter appeared in Denver as the group grew, and Duffield said it wasn’t uncommon for them to hold discussions in rented spaces at restaurants and bars. Members kept their identities secret until 1959, when they held a publicized meeting at the Albany Hotel downtown.

“The Denver vice squad was there waiting. They were risking their careers when they used their real names,” Duffield said. “They, unfortunately, took the pitfalls of that. The vice squad, within a week, arrested some of the members on charges of pornography, basically shut down the club and ran the whole thing out of town, effectively curtailing queer organization in one form or or another from direct political activism until the 1970s.”

That’s when people like Gerash and Mangan started organizing. In 1972, both men, along with Lynn Tamlin, Jane Dundee and Mary Sassatelli, came together to found the Gay Coalition of Denver.

Gerash said the group was “very non-hierarchical,” and found leadership through a system of rotating chairs.

“We thought we should not automatically copy what straight people do, as far as how they run things,” he told us.

They mostly met in apartments as they formed a legal strategy to end police harassment in their community. In addition to the bar raids, Denver Police were also known to entrap men cruising Cheesman Park and the Capitol lawn (see page 3 on the “Johnny Cash Special”).

The coalition filed their first lawsuit in October 1973, and used the process to access police records that showed gay men accounted for nearly every arrest over “lewd conduct” in the city. It was the ammo they needed to move things forward.

On Oct. 23, 1973, coalition founders and 300 supporters marched into the City Council chambers as legislators considered changes to Denver’s lewd conduct laws. 36 people signed up to speak, stretching an already late meeting long into the night.

Aaron Marcus, History Colorado’s first LGBTQ+ curator, told us Council’s decision hinged on the input of two members: Irving Hook, the city’s first Jewish member, and Elvin Caldwell, the first Black Council member in any city west of the Mississippi. While the sitting City Council president “didn’t want anything to do with” the protesters, Hook spoke up to give them the floor.

“He said, ‘No. These are citizens. They pay taxes. We have to listen to them,’” Marcus told us.

The Coalition and their supporters were successful. After the October council meeting, Gerash recalled Hook calling him to ask what they’d like to happen. At the next meeting in November, City Council voted to repeal three city laws related to crossdressing, loitering and renting rooms for sex that police used to harass LGBTQ+ residents, and one law that allowed entrapment through solicitation.

Gerash said he was floored.

“It was like the finest hour,” he told us.

Others were inspired, too. After one City Council meeting, Gerash said someone followed him out of city hall.

“We were walking down to an all-night diner after, we were celebrating our victory, and he tapped me on the shoulder and he gave me $2,000 cash,” he remembered. “We used it to open our gay coalition office.”

That office would later morph into the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center of Colorado, known today as the Center on Colfax.

The activists’ work, spurred by raids in bars, was a high point, but progress is seldom linear.

Aaron Marcus chronicled all of this history for his History Colorado exhibit, “Rainbows and Revolutions,” turning it into a timeline that wraps around the space. The Court Jester is present in the collection, mentioned in a 1965 Denver Post investigative series called “Homosexuals in Denver.” So are the raids and the 1973 “Gay Revolt” on City Council.

Originally, Marcus planned to end on a dour note, the passage of Florida’s “don’t say gay” bill this year.

He got some pushback on that, so he added one last entry on a recent Colorado measure that gives LGBTQ+ parents more equity under state law. Still, he said, he liked things ending ambiguously when he was planning the exhibit. As a historian, he knows progress can be cyclical, and he worried it would be disingenuous to paint too rosy of a picture as his timeline reached present day. It’s something he’s thought a lot about in the last few weeks.

“I’m just gonna be blunt here. You can see the hate that this community has always had to deal with. And, unfortunately with something like what happened at Club Q, it’s obviously still happening,” he told us. “I think it’s a statement that after you see 50 years of history, we are almost right back to the start of that timeline.”