The 2022 World Cup is about to kick off in Qatar as the world focuses on the small Gulf country.

This World Cup marks a few firsts: It’s the first to be held in the Middle East, the first to take place outside the tournament’s traditional May-July time frame, and the first to be held in a country as small as Qatar.

Since the event was awarded to Qatar in 2010, it’s also become one of the most controversial World Cups in recent memory.

The push to host the World Cup, and then the years of preparation for the tournament, have come as Qatar has sought to elevate its position on the global stage and boost its tourism economy.

The aggressive expansion of state-owned Qatar Airways — widely considered to be among the world’s best airlines, including by this reporter and many others at TPG — has helped, but the country hopes that the World Cup will enhance its global prestige even further.

Still, as the tournament begins, it’s important to be aware of the issues causing controversy, including the working conditions and deaths of migrant laborers, the persecution of LGBTQ+ individuals and the limitations on women’s rights in Qatar.

The World Cup is a major travel event, and this year’s, the first since the pandemic shuttered the world and closed borders around the globe, is a monumental one. At TPG, we debated how we should cover it. The culture, spectacle and incredible opportunity of the global event cannot be ignored, but neither can the controversies, hardships, and unease surrounding the tournament and its host.

While those traveling to Qatar for the games have likely finalized their plans, or come close to it, we feel that as a travel publication, it’s important to cover both elements: the practicalities of getting there and enjoying the historic event, and the ethical implications of what it took to make the tournament happen, and what it means to be there.

Here’s what you need to know about the controversies, and be sure to check out our guide for those who decide to make the trip: Everything you need to know about attending the 2022 World Cup in Qatar

Sign up for our daily newsletter

Migrant labor and deaths

Qatar has a population of about 2.94 million people, but only about 380,000 citizens.

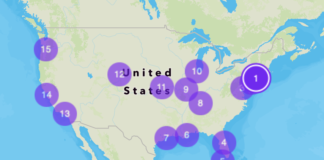

The rest of the population is made up of foreign workers. While some of them are professionals in industries ranging from energy to finance and IT consulting, the majority are low-income migrant workers from places like India, Nepal, Bangladesh and sub-Saharan Africa.

For the World Cup, Qatar has drastically developed and rebuilt its infrastructure, relying almost entirely on cheap migrant labor to do so.

The human cost, however, has been great. As workers have toiled in the heat — average high temperatures near 110 degrees Fahrenheit at the height of summer — to build stadiums, highways, hotels and public transit, many have suffered.

More than 6,500 workers have died while building infrastructure related to the World Cup, a 2021 investigation by The Guardian found, although the actual total could be higher.

Additionally, Qatar has been criticized over working conditions for some workers that “amount to forced labor,” or modern-day slavery, according to Amnesty International. Citing long forced working hours without breaks or days off, prohibitions from changing jobs or leaving the country, long waits to get paid, exploitative recruitment fees and poor living conditions in overcrowded workers’ dorms, reports have noted that while Qatar has some laws to protect workers and passed some reforms in 2020, these often go unenforced.

LGBTQ+ rights are nonexistent in Qatar

In recent years, global soccer governing bodies have made significant progress against the homophobia that is rampant in professional football.

From expressions of solidarity and allyship on the field to engaging with LGBTQ+ fans and supporters clubs behind the scenes and in the stands, inclusion has been a major objective for many clubs, leagues and countries.

Various regional and ideological flags emblazoned with club or national team crests are common among soccer fans, and in recent years, pride flags have notably joined those.

That’s why, for many fans, the decision to award the World Cup to Qatar was a slap in the face tantamount to undoing decades’ worth of progress, especially coming after the 2018 World Cup was held in Russia, another country that is hostile to LQBTQ+ people.

Sex between men is explicitly outlawed in Qatar and punishable by seven years in prison, according to a 2021 U.S. Department of State report. Homosexuality between Muslim men in the country is theoretically punishable by death under Sharia, according to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, a global advocacy group. However, there is no evidence of Qatar issuing the death penalty for homosexuality in the past.

Sex between women, along with other activities, such as being trans, are not specifically illegal but can draw extrajudicial abuse, according to the State Department and Human Rights Watch.

Despite assurances from the Qatari government that same-sex couples will be allowed to share accommodations and that all fans are welcome, some remain concerned that LGBTQ+ attendees will face discrimination and be at risk during the tournament. On Tuesday, a Qatar World Cup ambassador and former Qatari national team player, Khalid Salman, told German broadcaster ZDF that being gay is “a spiritual harm” and “damage in the mind.”

Australian player Josh Cavallo, one of only a few openly gay professional footballers and the only one playing at the top levels of the sport, has said that he would be “scared” to play in this year’s World Cup, though he would likely still play if given the chance (Cavallo, 22, has not yet played for the senior Australian national team, and is considered unlikely to be named to the country’s World Cup squad).

These fears and concerns are not just theoretical. Anti-LGBTQ+ laws in Qatar are regularly enforced. An activist was recently detained for holding a sign protesting the treatment of queer people in Qatar, while an October report from Human Rights Watch documented beatings and lengthy detentions of LGBTQ+ individuals by Qatari authorities.

Women’s rights in Qatar

Female visitors and foreigners in Qatar are generally safe and do not face restrictions on their movements. There is no requirement to wear a hijab in public and the dress code in the country is relatively relaxed. However, women are expected to dress somewhat modestly to avoid offending the local community, and the same applies for men.

Things are very different in law and in practice for Qatari women, however.

Although women enjoy more rights and relative autonomy than in some other parts of the region, there is still an oppressive cultural and legal framework in place that effectively curtails their independence.

A guardianship system forces women to obtain a male guardian’s permission before marrying, studying or traveling abroad in some situations, working in certain jobs, serving as a child’s primary guardian or accessing certain sexual and reproductive health services, according to Human Rights Watch.

The Qatari government disputed the claims in the 2021 Human Rights Watch report and pledged to investigate what it characterized as illegal treatment of the women cited in the report, but according to Amnesty International, that investigation never began.

Perhaps even more troubling: Female fans who attend the World Cup could have little recourse if they are victims of sexual assault while in Qatar, The Athletic reported, citing cases in which women who were assaulted in Qatar were prosecuted by the government for having extramarital sex rather than seeing their assailants put on trial.

Why FIFA chose Qatar, and why the World Cup is in November

The simple, all-encompassing question raised in the 12 years since FIFA awarded this year’s tournament to Qatar has been: Why?

The tiny yet extremely wealthy nation has little existing football culture. It did not have the infrastructure to hold the tournament when it won the bid. Its summertime climate is inhospitable for the game and, as a nation ruled under strict Islamic law, the culture of loud, bawdy celebration, drinking, partying and occasional hooliganism that surrounds the tournament seems to be at odds with the country’s values.

For Qatar, the benefits are great, though. The nation seeks to broadcast a cosmopolitan image like that of nearby Dubai, telling the world it’s open for business and seeking to expand its economy beyond natural gas and other resources while glossing over a record of human rights abuses. Hosting the tournament grants Qatar a global platform few other events could match.

According to numerous reports and allegations over the past decade, the appeal of hosting the games was strong enough for Qatar to tip the scales in its favor by bribing FIFA officials.

Qatar and both past and current FIFA officials strongly deny any wrongdoing. Nevertheless, a seemingly endless stream of investigations — both by governments and by journalists — have found evidence of corruption, including cash bribes, suspicious investments in countries that cast their votes for Qatar, nepotistic hiring and more. Similar allegations dogged Russia during the lead-up to the 2018 World Cup.

Initially, Qatar said that it could host the tournament during June and July just like every other World Cup — when most of the world’s top leagues, including in Europe, are on break — despite the brutal heat in the Gulf. The plan was to build indoor, air-conditioned stadiums that would allow play to take place at more manageable temperatures.

Qatar quickly scrapped that plan, however, necessitating a move to November and December, when the temperatures are closer to 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

That will force the top leagues to pause their seasons midway, creating logistical problems for schedules. The calendar is particularly difficult in England, where the national mourning period following the death of Queen Elizabeth II led to a week of suspended matches that need to be rescheduled.

There are also questions about whether Qatar will be able to finish building other infrastructure for the tournament in time, along with the accommodations for millions of spectators, which include new hotels, refurbished shipping containers and tents.

The country hopes that the spectacle of a successful tournament, seen around the world and promoted by soccer influencers, will overshadow the criticism, but as objections continue to pour in, it’s not clear whether that strategy will be successful.

Despite FIFA’s recent pleas for players to “focus on the football” and not discuss human rights issues during the tournament, English and Welsh teams plan to ignore that, with English striker and captain Harry Kane still set to wear a “OneLove” armband in support of LGBTQ+ rights during the tournament.

The Danish national team will wear toned-down uniforms with subdued logos in protest of Qatar, including a black alternate jersey meant to honor migrant workers who allegedly died during construction for the tournament. German fans held signs during games earlier this month urging a boycott of the tournament, and the Welsh football association said it would consider sourcing safe houses for LGBTQ+ attendees and said it “can’t guarantee safety” of all fans. This week, Scotland-based multinational beer company BrewDog launched an ad campaign protesting the tournament and saying it would donate profits to human rights causes, although it was criticized for saying it will still show matches in its own pubs and for past allegations of treating its own workers poorly.

What to know if you plan to attend the World Cup in Qatar

If you find yourself with a last-minute ticket or opportunity to attend the World Cup in Qatar and decide to attend, there are a few important things to keep in mind.

Standard visas to enter Qatar are not being issued during the tournament, and only ticket holders can get an approved “Hayya Card,” which authorizes entry to the country. The card is also required to attend matches.

Alcohol consumption and drunkenness are forbidden in public, although the World Cup will offer designated drinking sections on the stadium grounds before and after games. There will also be a FIFA fan zone where drinking is allowed in the evenings. Clothing should be relatively conservative, with knees and shoulders covered.

The tournament is scheduled to begin Nov. 20, with the final set to take place Dec. 18.