(Getty Images)

(Getty Images)

Rochester political scientists discuss what happens when election deniers run for office, and how US democracy may die ‘by a thousand cuts.’

With the United States midterm elections just around the corner, three University of Rochester political science professors consider what’s at stake. Through the lens of their respective research focuses, Gerald Gamm, Gretchen Helmke, and James Johnson discuss political hyperpolarization, what happens when losers don’t concede elections, the likelihood of civil war, and the outlook for US democracy.

In this article:

Gerald Gamm on the recent hyperpolarization in US politics

Gerald Gamm is a professor of political science and history at the University of Rochester. The coauthor of the forthcoming book Steering the Senate: Party Competition and the Emergence of Leadership, 1789–2022, Gamm studies Congress, state legislatures, the culture war, and party polarization.

(University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

When did we as a nation become so polarized?

Gamm: Partisan polarization is a relatively new development in American politics that began about 40 years ago. Through most of the 20th century, there was more overlap between the political parties than there was division. It’s only since the 1980s that the parties begin to divide systematically along ideological lines.

What exactly happened in the 1980s to cause this divide?

Gamm: A number of events: the civil rights revolution, which guaranteed basic rights for Black people in the South and enfranchised Black adults in the South. That ended the historical allegiance of white southerners to the Democratic Party and, as a consequence, a lot of white southerners became Republicans, while many of the more liberal Republicans in the Northeast started drifting toward the Democratic Party. That marked the start of the ideological sorting of the parties.

The other big events of the 1960s and 70s were the beginnings of the culture war and the introduction of issues such as abortion, women’s rights, and the rights of gay people into our politics. It’s not until the 1990s or the early 21st century that the culture war issues neatly sort along party lines, but the beginnings date back to the 60s and 70s. By the 21st century, you have parties that are increasingly ideologically different from one another.

For about the last two decades polarization has been in overdrive. Why?

Gamm: People’s views of Bill Clinton diverged sharply by party in a way that views of past presidents hadn’t diverged; the same happened again with George W. Bush. The Obama presidency was an unusually polarizing presidency; a lot of people came to believe the lie that he wasn’t even a legitimate president.

“We have a world that’s been growing polarized—at first steadily, and then increasingly so—for 40 years, where we basically have already divided into tribes over every conceivable issue and where our tribes have started to become more meaningful to us than the issues themselves.”

During the Trump presidency, Americans took sides more than ever before. On top of this came growing concerns about economic inequality and unfairness, and the inability of globalism to deliver jobs and meaningful work for a large proportion of Americans. In addition to Trump’s populism, you have people’s concerns about the nation’s borders, growing nationalism, and a deep-seated suspicion of elites. And if that weren’t enough—the pandemic arrives.

By 2020, we have a world that’s been growing polarized—at first steadily, and then increasingly so—for 40 years, where we basically have already divided into tribes over every conceivable issue and where our tribes have started to become more meaningful to us than the issues themselves. And then the pandemic acts as an accelerant and makes everything worse.

Are we going to sink further into division and dysfunction?

Gamm: Every year for the last 20 years I have thought that this is as bad as it can possibly get. And then somehow it manages to get worse. So, I’ve given up making predictions for the future. I have a residual faith in American democracy. There’s a piece of me that thinks somehow we’re going to figure this out.

The worst thing that has happened in American politics in the last five years hasn’t just been polarization. It’s been the conviction of a very large number of Americans that democracy itself has failed. And no one has expressed that conviction more vividly than President Trump. He’s led a movement to persuade people that elections can’t be trusted; that election officials can’t be trusted; that majorities are fraudulent. And that, therefore, democracy itself is fraudulent. Of all the developments—much worse even than polarization—it’s this development that calls into question the viability of the whole American experiment in democracy.

What does distrust in US democracy mean for the midterm elections?

Gamm: The greatest threat that we face right now is that we can’t even agree anymore that elections work. That’s new in American democracy. Even in the 19th century, even with massive numbers of people disfranchised, even on the eve of the Civil War, no one doubted the basic integrity of the American electoral system. The emergence of that non-agreeing on electoral outcomes as an issue strikes me as a genuine emergency for our Republic.

What’s fascinating is that while we have this existential issue about the survival of our democracy, it doesn’t appear to be shaping most people’s electoral decisions. Remember, there are hundreds of people running for office in this country right now—including people running to be governors and secretaries of state and United States senators and members of the House of Representatives—and many of them, all Republicans, reject the results of the 2020 election and thus declare their refusal to accept legitimate elections, in the absence of any supporting evidence. For me, that should be the single defining issue of this election. But it isn’t.

Do you expect both parties to accept the midterm election results?

Gamm: In the Republican primaries we saw very little disputing of election results. Going back to 2020, there was no disputing of election results for any office other than the presidency. One of the oddest and scariest outgrowths of the 2020 election was that on the same ballots where we elected our Congress and elected our governors and state legislators, we also elected our president.

“Of course, I’m worried. I went into the study of American politics thinking I was studying the world’s oldest and most stable democratic political system. Now I’m deeply worried about the sustainability of the democratic experiment in America.”

And yet, there appears to have been very little questioning [by those who bought into the “stolen election” narrative] of how those ballots were legitimate for any office other than the presidency. That’s just intellectually inconsistent. Maybe I’m naïve, but I don’t expect any real disputing of the results of the midterm elections. Yet, I do think that it’s a staging ground for how the country reacts to the presidential election in 2024.

Are you worried about the survival of our democracy?

Gamm: Yes, of course, I’m worried. I went into the study of American politics thinking I was studying the world’s oldest and most stable democratic political system. Now I’m deeply worried about the sustainability of the democratic experiment in America.

Gretchen Helmke on democratic backsliding and ‘the big lie’

Gretchen Helmke is the faculty director of the University of Rochester’s Democracy Center and the Thomas H. Jackson Distinguished University Professor. She is a founding member of Bright Line Watch, a team of nonpartisan academics that polls the public and experts at regular intervals about the health of US democracy.

(University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

What are you and your colleagues in Bright Line Watch watching for in the midterm elections?

Helmke: We just fielded a new Bright Line Watch survey this week: we did one wave in October right before the midterms and will field a second wave afterwards. An important survey indicator asks about free and fair elections, which was hyperpolarized in 2021. Essentially, we’re asking how well the US meets this standard.

In 2021, we found that only 22 percent of Republican survey respondents regarded elections as fraud-free, compared to 71 percent of Democrats. In this week’s survey—American Democracy on the Eve of the 2022 Midterms, October 2022—we saw that the gap narrowed a bit between the two camps but nevertheless remains gigantic: about 67 percent for Democratic voters rate US elections as fraud-free, versus just 27 percent of Republican voters.

We’ll repeat the survey right after the midterms to see whether the gap narrows or broadens and whether such perceptions roughly track with which party gains the majority in Congress.

A second important point is the “conceding an election loss” indicator in our surveys, where we’re asking respondents how important they think it is for the losing candidate to publicly acknowledge the winner. When we asked this question in 2021, more than three quarters of Democrats said conceding an election loss was important for democracy. But just over half of Republicans agreed. Obviously, there’s a deep connection: If you thought elections weren’t free and fair, then you probably thought it’s less important to concede because the election wasn’t legitimate in the first place.

This week, we changed the question and asked specifically about the upcoming Congressional races and found that, in principle and in advance of the midterm election, 79 percent of Republican voters and 94 percent of Democratic voters respectively do think that all losing Congressional candidates should concede their defeat. We will see the extent to which those numbers shift depending on what happens in the wake of the midterms and how many candidates cry foul after the election.

Have Americans become less committed to democracy?

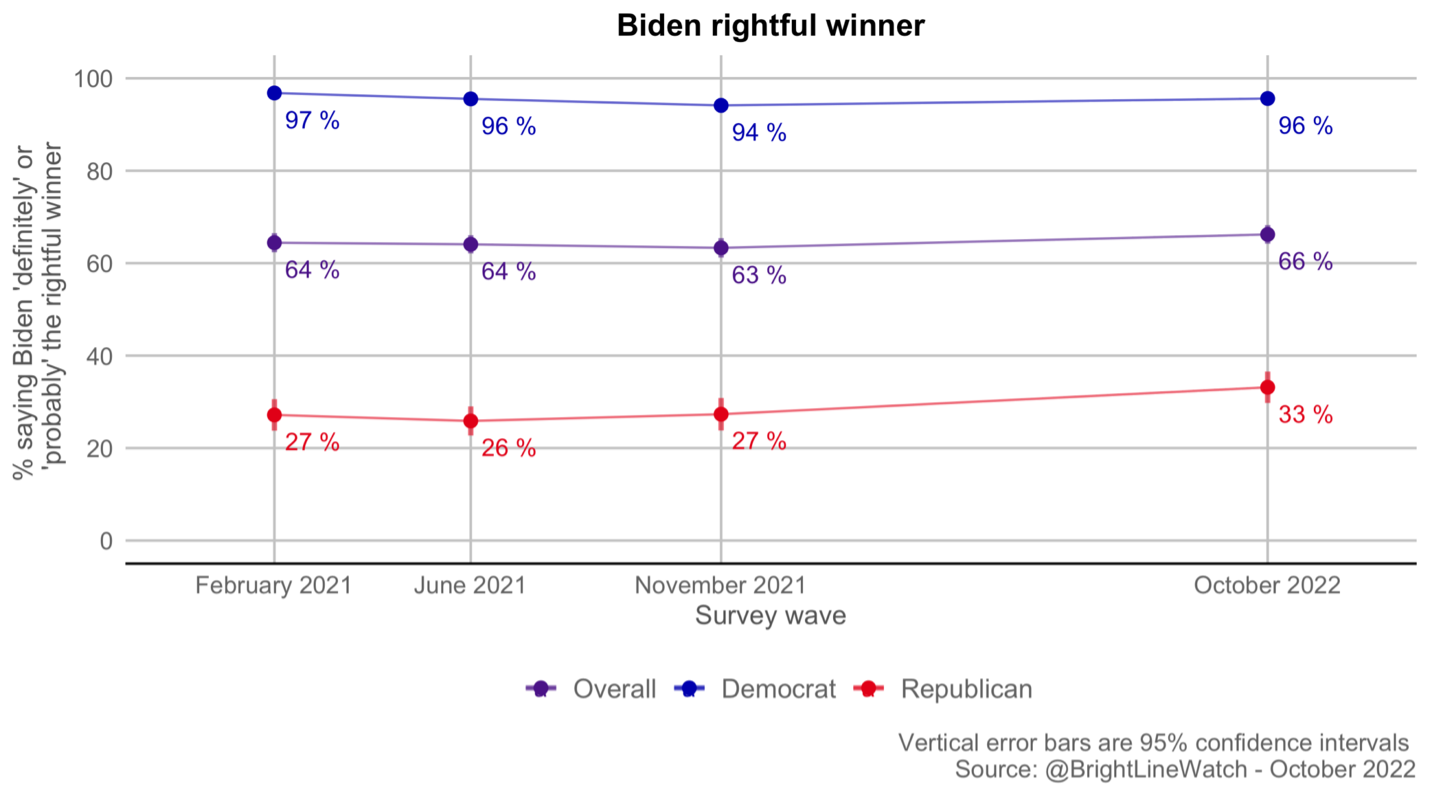

Helmke: I don’t think that the fundamental problem here is people’s commitment to democracy as an ideal. I think the problem is that we lost an essential feature of any democracy—the willingness of parties to lose elections. We now have a situation in which one of the major parties is signaling that it’s no longer willing to do that; a problem obviously most closely associated with Trump and the 2020 election. In 2021, only about 27 percent of Republicans admitted that President Biden is the rightful winner. Now, in our October survey, the number has moved slightly up, which is better, to 33 percent of Republican voters who accept Biden’s election win.

How has Trump’s refusal to accept his election loss in 2020 spilled over into the midterm elections?

Helmke: It’s spilled over in a number of ways. There are, for example, now hundreds of election deniers on the ballots across the country. A candidate like Kari Lake, who is running for governor in Arizona, is explicitly using Trump’s rhetoric to undermine the validity of these elections and won’t pledge to accept a loss. That kind of copycat rhetoric signals to people that an election is only valid if you win and cuts against the basic principle of a democracy—the willingness of parties to lose elections.

“What’s so pernicious about the big lie is that the vast majority of Trump supporters still claims the democratic principle of free and fair elections was violated. In denying Biden’s legitimacy, they likely think they are protecting democracy, not undermining it.”

Most striking in our latest survey findings is that the polled academic experts place about a 75 percent chance on some high-profile Republican candidates in these midterm elections refusing to concede their election loss. These experts also rate the prevalence of the 2020 election denialism among Republican candidates, who are now running for statewide office, as the most abnormal and important event of the past year and one of the most extreme events to take place since 2016.

Now, Republican elites seem to be aware of the fact that Trump legitimately lost the election. Nevertheless, they are very wary of challenging him because they’ll get blowback from him and from the base, and we’ve seen how that can end in primary defeats.

What’s so pernicious about the big lie is that the vast majority of Trump supporters still claims the democratic principle of free and fair elections was violated. In denying Biden’s legitimacy, they likely think they are protecting democracy, not undermining it.

What keeps you up at night?

Helmke: What keeps me up at night is that people no longer share the same set of facts about elections and that the legitimacy of the electoral process has been eroded fundamentally and has become so polarized. All that makes it very hard to sustain a democracy.

“I don’t think the end of democracy in the United States, if it happens, is going to be a single event. Instead, I think it’s a series of piecemeal, incremental steps.”

Also very concerning is the politicization of the electoral process itself: not just this effort to put candidates on the ballot who are election deniers, but to potentially challenge every local race, and to try to insert people as poll watchers who may already be convinced that the system doesn’t work.

Related to that are the threats we saw against people who are doing heroic work by serving as poll watchers, working on election boards, and trying to just do the basic work of counting votes. They’re receiving threats against their safety and the safety of their families. If those threats accelerate in this election cycle, it’ll really be a problem. It’s a strategy of trying to throw spokes in the wheel of elections, trying to undermine their legitimacy.

Is US democracy acutely in danger of coming to an end in our lifetime? Are we inching closer to civil war?

Helmke: I don’t think the end of democracy in the United States, if it happens, is going to be a single event. Instead, I think it’s a series of piecemeal, incremental steps. In a way we are already coming apart: if the majority of voters in one party won’t accept the results of an election, then that’s already a sign that democracy is not functioning.

Helmke: Let me be clear—there’s absolutely no evidence that there’s been any election fraud that has swayed the 2020 presidential election in any way whatsoever. There’s no factual evidence of that and no court in the country has found any evidence of that, and yet here we are where most people in one party believe that exactly that happened. It’s not that we’ve lost free and fair elections in the US; it’s that people believe we’ve lost them. And that’s a real problem for democracy. But will this lead to civil war? There are so many factors that contribute to civil war, there isn’t going to be a straight line just like that.

James Johnson on voting procedures and antidemocratic outcomes

You argued in your recent book that attempts to make voting more convenient have made it harder to guarantee voting secrecy. Since then, several states have rolled back some of these convenient voter options. Are you satisfied?

Johnson: I think that the arguments about convenience voting are confused by both Republicans and Democrats. The Democrats tend to think that making voting more convenient through absentee ballots and basically allowing people universal excuses for not voting on election day itself, is really going to increase turnout, and that increased turnout presumably will work to their own advantage. Republicans meanwhile think that convenience voting has a discriminatory impact in partisan terms. But neither of those things is true.

What we know is that making voting more convenient makes it more likely that people like you and me will vote, because we’re the high-turnout voter demographic—middle class, educated, suburban—and we’re very likely already going to vote. But the people who are not voting are not moved by convenience voting.

Is that why you suggest mandatory voting? How would that work?

Johnson: Our argument was that if you really want to increase turnout, and you want to eliminate some of the ways that people can be intimidated or prevailed upon to vote in particular ways, you’d have to introduce mandatory voting because that would eliminate the incentives for political parties to engage in untoward activities, like turnout buying or voter suppression. Australia, for example, has compulsory voting. In Australia you have to go to the polls; if you don’t go—you’ll get fined. Once you get to the polls, of course, you can do all kinds of things: you can simply vote for one of the alternatives on offer, you can spoil your ballot, you can write in “Mickey Mouse,” you can write “none of the above,” whatever you want. But you have to go to the polls, which increases turnout to relatively high levels. And with increased voter turnout, parties have to appeal to a broader array of voters, instead of just the extremists in their parties.

Is mandatory voting your answer to society’s hyperpolarization?

Johnson: I don’t think it’s the answer, but I think it would help. It would present an incentive to parties to try to appeal to a wider array of voters, other than their confirmed Republican voters or confirmed Democratic voters. Right now, they have no real reason to try to appeal more broadly to anybody; instead, they keep playing to the more extreme views of their base. That’s because the base are the people who both parties know will turn out and vote for them.

“Right now, we basically run voting by bake sale.”

Of course, if we had mandatory voting, you would have to shore up the institutional infrastructure of casting, counting, and monitoring votes, instead of relying on so many volunteers. You’d have to fund the institutional infrastructure to make that work. Right now, we basically run voting by bake sale.

Practically, the way mandatory voting works in other countries, is that there’s some sort of consequence for not going to the polls. In some places, it’s a small fine, not much. In some places it means you can’t get your passport renewed. In others you wouldn’t be eligible for certain kinds of government policies or programs, which I think is a bit draconian.

In your 2011 book, you and your coauthor argued that the “pragmatic role of democracy” was not so much in achieving consensus, but in addressing conflicts and “structur[ing] the terms of persistent disagreement.” A decade later, where do we stand?

Johnson: I think we’ve lost a lot of that ability. What really brought that home to me wasn’t even national politics but what happens at the local level. Last year, at my local school board meeting, some parents were trying to defend a voluntary after-school program about the variety of families that live in our town—gay, straight, lesbian, single parent, etc. Yet people from the community objected to the program. At the school board hearing, some in the room were yelling “pedophile” at the people who were trying to defend the program. That kind of behavior over a voluntary after-school program in a local middle school is, in my estimation, crazed. It suggests a level of hostility and a level of disagreement that mirrors what’s at stake in the country.

“We currently have some 290 election deniers across the country running for office in the midterm elections. Some of them are running for positions of secretary of state in various states. Of course, the secretaries of state are the ones who administer elections.”

Unfortunately, that behavior ties in directly with the national situation in which for many people, the idea of losing an election is anathema. They can’t fathom allowing the other side, whether that’s Democrat or Republican, to hold power. You saw this early on to a degree with the bumper stickers when George W. Bush was president that would say “not my president.” Oh yes, he was your president. Maybe not the one you voted for. You lost that election. Ultimately, that’s what January 6 was about—not being willing to recognize the possibility of losing. And if that’s the case, you’re not playing in the same game.

When you wrote that book in 2011, did you imagine that a mere decade later US democracy would be in such dire straits?

Johnson: No, I really didn’t. I’m 67. Not in my lifetime has the refusal to concede an election loss ever been an issue. Now it is. We don’t just have the former President of the United States but also his supporters who turn up and invade the Capitol Building in an attempt to disrupt the certification of a lawful election. We currently have some 290 election deniers across the country running for office in the midterm elections. Some of them are running for positions of secretary of state in various states. Of course, the secretaries of state are the ones who administer elections. What does it mean to have elected representatives who refuse to acknowledge the outcome of legitimate elections, even when the aggrieved party—in this case, former President Trump and his supporters—has lost more than 60 court cases when they were trying to show fraud and malfeasance in the 2020 election? It’s frightening.

Of course, something to consider is that a lot of what’s happened in this country results from our institutions that are creating non-democratic outcomes. By that I mean that we’ve had five minority presidents so far—they win the electoral college but lose the popular vote. That’s an antidemocratic outcome and it happened most recently with George W. Bush in 2000, and again with Trump in 2016.

Are we in danger of losing our democracy?

Johnson: Worldwide, we have quite a few countries that are moving in the direction of—or have already slid into—authoritarian rule, such as Turkey, Brazil, Hungary, Poland, India, the Philippines. That’s a lot of people, a lot of constituencies. Some of these instances are quite dangerous and I think we’re at an important inflection point in this country.

I don’t want to be a Cassandra, but if we have another election in the US that runs like the last one in 2020, in which one candidate refuses to recognize the outcome of the election, we’re in trouble. As Gretchen’s work shows, we’re not losing our democracy over one single event. Rather it’s death by a thousand cuts.

Read more

Category: Featured