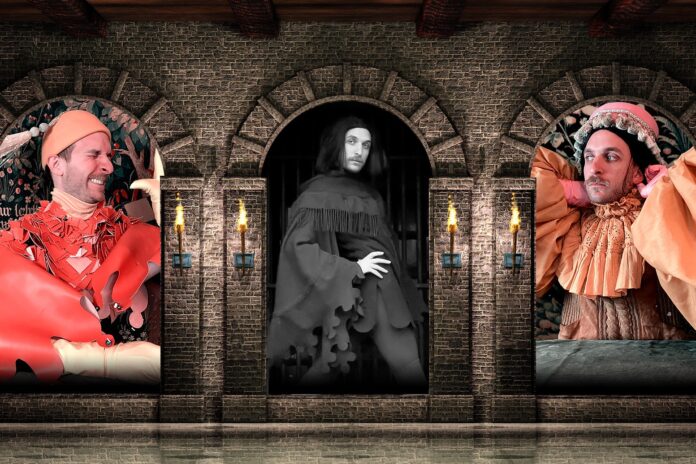

What would it be like if, in the Middle Ages, there was a peasant who made influencer-style videos about feast days, Lent, the bones of saints, and his coping mechanism for surviving the plague (buying hats)? Well, he exists on TikTok as @greedypeasant, the quarantine creation of costume designer Tyler Gunther, and he is delightful.

In Gunther’s videos, the wholesome and people-pleasing Peasant presents the miseries of medieval life with the chipper narration of modern-day content creator.

Advertisement

“I talked to the king today,” he tells the camera in one video as he nibbles on a chicken wing. “Now he wants everything purple. Purple! I’ve seen purple like once in my life. From a distance. But yeah, OK, everything can be purple. No problem. I’ll go buy purple at the market. ‘Excuse me, do you have any purple? I’m all out.’”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

In creating this character, Gunther ignores the romantic, chivalric tropes of the Middle Ages; his Peasant instead lives in the muddy, grubby, disease-ridden version of the time period, but subverts our ideas of the Dark Ages by reveling in dramatic, colorful clothing and the occasional donut, among other simple pleasures.

If you watch every one of his TikToks, as I do, you will get to know some biographical details about the Peasant’s personal life. He makes a living as a junior pageant planner. His twin brother is a monk who has taken a vow of silence. His gruff father wants him to grow up and get a good honest job as an executioner. He tries too hard to relate to his friends. He dreams of one day designing his village’s Christmas pageant. He is gleefully queer and goes on dates, one of which completely flops when the incorruptible body of a saint he and his date have gone to see turns out to be, disappointingly, headless.

Advertisement

Advertisement

But mostly, what we know about the Peasant is that he lives for pageantry. He adores theatricality in every form, whether it comes from a particularly bold hat or from the macabre obsessions of the medieval church. And he lives, mostly peaceably, during an era of human existence—medieval times—that has become, in many ways, a modern shorthand for a more barbaric age, marked by mass death and persecution.

Advertisement

Something about this dichotomy makes for a deep and delightful experience. The Peasant approaches the Middle Ages as camp. But even in subverting ideas of medieval life, Gunther is getting to a more complex understanding of human history.

“Medieval Europe was incredibly weird, and incredibly queer,” said Sara McDougall, who teaches and researches medieval history at the City University of New York. “It played with gender and played with color and shapes and fashion. And there was an obsession with men’s fashion, and how men look.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

She said that history shows plenty of Middle Ages “men obsessed with hair, and men obsessed with wearing pointy shoes. Men criticizing other men for wearing pointy shoes as a way to be effeminate—or as a way of provoking male desire.” (The sight of male ankles, in particular, was supposed to have provoked that desire, she said.)

And who could deny that there are drag-like elements of the medieval church? Not the Peasant, who, at one point, begins a story by talking about a “‘High Mass’ concept that was introduced where everything was, like, a little bit fancier.” There’s something inherently fun about such blatant queerness in a religion-drenched period.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Kevin Uhalde, who studies late antiquity and the early Middle Ages at Ohio University, argued that the Greedy Peasant’s matter-of-fact sexuality was an interesting and useful way to challenge rigid conceptions of history.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“It is worthwhile to try to shake up people’s ideas about the past, because they tend to be so deeply entrenched,” he said. “While the political and legal history of the Middle Ages are very important, focusing just on those topics leaves out the vast majority of the human populations that weren’t directly involved in any of that.”

Fiction, he said, such as the medieval world created by Gunther, “challenges us to try to be more open and empathetic to people who have never been written into history.”

Historians know that men in that period were punished for sodomy, and there are records of men writing of intense love for one another. But the Peasant, with his cheerful and mundane musings, does not live in terror. (He jokes occasionally about the prospect of eternal damnation, but signs indicate the peasant’s guilt has more to do with sins of omission or just not being nice enough to his mom.) Nor is he consumed by a great passionate love. He just gossips with his coworkers, practices his ditch-digging yoga pose, and shares his astrological signs during confession. The Peasant’s whole world is queer—his two nun friends are canonically lesbians—and Gunther’s trick is that he refuses to let the bigotries of the past (or present) step into this fever-dream medieval fantasy.

Advertisement

Advertisement

On his website, Gunther acknowledges this, writing: “Greedy Peasant seeks to broaden our understanding of the queer imagination during the middle ages.” It’s an exercise in getting “people to use their imagination a little bit with the past.” (Gunther declined to talk to Slate on the record about the Peasant in an effort to “keep him and his world as medieval & mysterious as possible.”)

Other characters that inhabit the world of the Peasant, and are voiced or acted by Gunther, include a “lady-in-waiting” who isn’t sure what she is waiting for, gossipy medieval reliquaries (one competes in RuPaul’s Drag Race), and a medieval doctor who relies just a little too heavily on bloodletting. All revel in a contrast of anachronistic fiction that somehow celebrates the strangeness of that age—and the strangeness of today. The petty and the gothic, the upbeat and the comically dark. In my favorite of Gunther’s videos, a nun receives a relic donation and has to sort out which bones belong to which saints. She knows these bones’ origins are dubious, but it doesn’t dampen her cheerfulness. There’s no sign of religious piety here—just the morbid thrill of participating in something deeply weird. “Amazing,” she says, with glee. “This is why I became a nun.”