Glenn Burke was an amazing athlete, extremely likable and the glue to the clubhouse. Yet he was forced out of the major leagues after four seasons because of who he was: Major League Baseball’s first openly gay active player.

There hasn’t been a second — even though more than four decades have passed since Burke played outfield for the Dodgers and A’s.

MLB speaks of its advocating inclusion, diversity and equality. Twenty-nine of 30 teams are staging Pride Nights this month — the exception is the Texas Rangers — and the A’s have named their Pride Night on Friday to honor Burke. but the game’s changing culture hasn’t provided enough comfort for any gay players to come out of the closet.

“You’d hope it would be better now, but the evidence doesn’t support that,” author Andrew Maraniss said. “No gay player in the major leagues has come out since Glenn Burke. The level of homophobia is too strong.”

Maraniss wrote “Singled Out: The True Story of Glenn Burke,” which was published in March and chronicles Burke’s life. He said it’s not the fault of the gay player as much as “a society that still has much work to do to create an environment where a player would feel supported.”

Progress has been made. Billy Bean was named MLB’s ambassador for inclusion in 2014 and later became vice president and special assistant to Commissioner Rob Manfred, communicating with players about LGBT issues and sharing his own story. Bean had a six-year MLB career that ended in 1995.

Burke was open about his sexuality and knew teammates and management were aware of it. Bean did not feel he could come out until four years after his final big-league game.

“I feel we’re all pointed in the right direction,” Bean said of baseball being more accepting of a gay player. “The league across the board continues to grow and cultivate relationships that are the indicators and signs that a player needs to see.

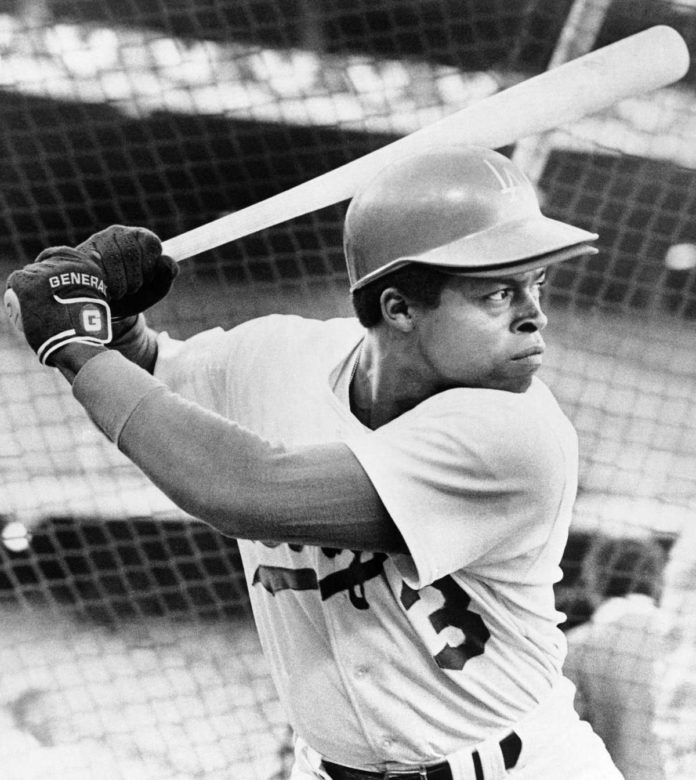

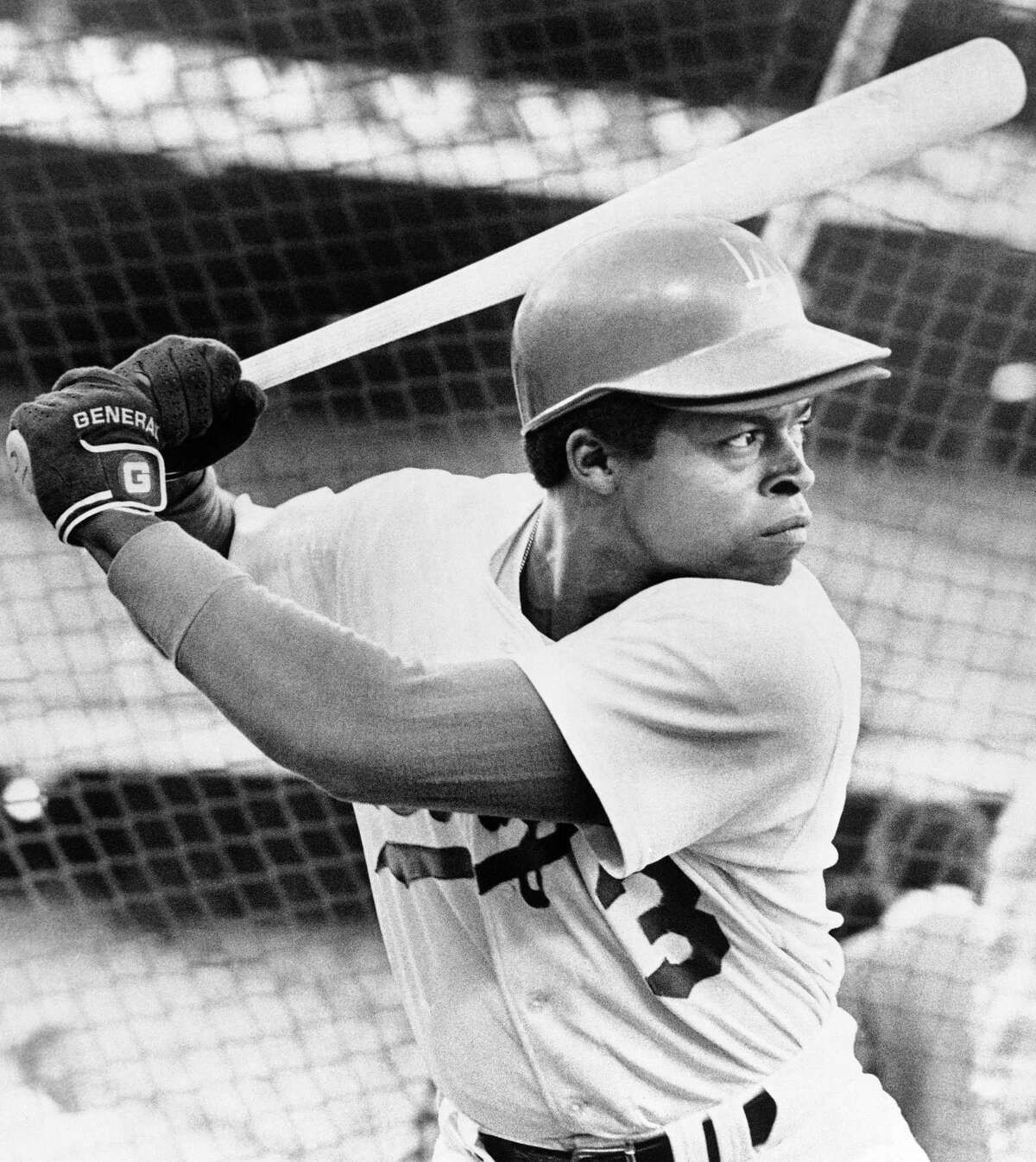

Glenn Burke taking some batting practice at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles on Monday, Oct. 4, 1977 was given the call to start at center field for the Los Angeles Dodgers on Tuesday when they open the National League Championships against the Philadelphia Phillies.

LM / Associated Press

“When I was a player, there was no education, no messaging to players about social issues, no wellness conversations, no conversations about eliminating sexism or identifying sexism in the workplace. There’s so much that goes with playing in the major leagues now, and baseball completely understands and prioritizes that, and now we have allocated resources.”

Times have changed enough that players such as A’s outfielder Mark Canha and Giants outfielder Austin Slater are open about supporting a gay player.

“I would 100% embrace an LGBTQ+ person if they’re my teammate, even if they were on another team,” Canha said. “I would feel obligated to voice my support on social media. I would hope that they would be well-received in baseball. I would hope we’re at a point in 2021 where people are accepting of that and would embrace that.

“The more people that are popular in the game who voice their support, I think it’ll help the cause and help kids growing up to understand that there are a lot of different types of people who live their lives in different ways. … I’ll do my best to spread that message across baseball.”

Slater said, “You don’t want someone living in fear they’re going to be chastised because of their sexual orientation. It saddens me that someone feels that way, not only as a co-worker but a teammate.

“I would hope we can embrace that person and help him so he can feel comfortable. I think hopefully with all the movement and awareness not only on social media but around the globe, guys realize it’s important to be inclusive in baseball and sports.”

While both players speculate there’s a good portion of baseball that would accept a gay player, they realize it’s far from universal. Canha said, “I know a lot of people (in baseball) who don’t accept or support” the LBGBTQ+ people, let alone a potential teammate. And Slater wonders about drawbacks in the response, saying a player is “not only fearful that his teammates wouldn’t accept him but the reaction he’d get with the media making it a national story.”

Giants manager Gabe Kapler has his own efforts promoting inclusion, and said, “Absolutely no discrimination should be tolerated or accepted in any clubhouse. A gay player should absolutely be welcomed. However, I am also aware that coming out is a very personal, individual decision. I also know that it isn’t enough just to say those words.

“Creating an inclusive and welcoming atmosphere is something that requires constant work, effort and attention from everyone in an organization. I’m glad the Giants have begun to take those steps, and I’m glad we’re committed to taking more.”

It’s a far cry from Burke’s days. The Berkeley High School legend had such potential that then-Dodgers coach Jim Gilliam said Burke could be “another Willie Mays,” significant considering Gilliam was a close friend of Mays from their playing days.

Burke did not receive support from management either in Los Angeles or Oakland. Tommy Lasorda, his manager with the Dodgers, refused to acknowledge the sexuality of his own son, Spunky, even after Spunky died of AIDS in 1991. Burke and Spunky were friends.

“We all liked Glenn a lot not only on the field but off the field,” former teammate Dusty Baker said. “He was always fun-loving. We heard about some of the things baseball and the world might not have been ready for at that time. … A lot of people were guessing. But it didn’t change our idea about him personally.

“Not only did I stand up for him, but he was like my little brother. There were rumors about him and Spunky. I tried not to be judgmental of a person’s sexual preferences or anything. That’s what I was taught. Glenn was a heck of a dude, and I tried to help him off the field.”

Burke was good enough to start Game 1 of the 1977 World Series. But after the season, Dodgers general manager Al Campanis tried to pay Burke $75,000 to get married. “You mean to a woman?” asked Burke. Once Burke refused, Campanis looked to trade him and dealt him to the A’s in May 1978.

In Oakland, Burke played the rest of the 1978 season and two months into 1979 before quitting in early June. He tried a comeback in 1980, thrilled about the A’s new manager, Billy Martin, who had a similar background, playing ball at Berkeley High and Oakland’s Bushrod Park. However, Burke discovered Martin was also homophobic and often spouted slurs while describing Burke, saying he’d refuse to play him.

Burke had knee surgery and, after his recovery, got demoted to the minors. Realizing Martin had no plan for him at the MLB level, Burke, in his athletic prime at 27, called it quits again after just 25 games, this time for good.

“Baseball had never been confronted with someone like Glenn before,” Bean said. “All the men who mistreated him or did not know how to accept him had never been given any resources to act otherwise. It’s essential we learn from it.”

While his sexuality was known within baseball, Burke didn’t tell his story to the media until 1982 when he was featured in Inside Sports magazine (“The Double Life of a Gay Dodger”) and on the “Today” show with Bryant Gumbel.

“He called me when Inside Sports was doing an article on him,” Baker said. “I said, ‘what do I tell them?’ He said, ‘You tell them whatever you want.’”

Maraniss, noting Burke’s .237 batting average and two career home runs, said it’s unfair to judge the outfielder’s statistics because of what he was facing.

“You could say Glenn played himself out of the major leagues with his numbers, but the mental aspect is so important, and just imagine if you’re walking on eggshells the whole time, wondering what people are thinking and saying about you, hearing the F-word in the stands and having your GM offer you a cash bribe to cover up your sexuality,” Maraniss said.

“No way you can fully develop your athletic abilities in that kind of environment.”

At the same time, Maraniss said he believes the game could be ready for openly gay players.

“A good segment of society would celebrate a gay player in the majors and admire his courage,” Maraniss said. “Lots of fans would get behind that player. He’d have the most popular jersey in the major leagues.

“Think of how inspiring it would be to young gay kids. Say a boy playing baseball who’s 12 or 13 and has that role model in the major leagues. The benefit of that would be immeasurable and inspiring in a way we have not seen before.”

The right environment would mean a team and teammates who would publicly embrace a gay player and call his presence no big deal — teammates such as Baker, who supported Burke during their Dodger days. Baker had learned from the legendary Hank Aaron, his Braves teammate, to be a mentor for young players, especially young Black players. Burke and Baker are also forever connected for the first high-five, which Burke offered at home plate after Baker hit his 30th home run on the last day of the 1977 season.

After his baseball career, Burke enjoyed hanging out in the Castro district, and he was dominating in a gay softball league. The good times didn’t last. Burke was plagued by money and drug issues and was hit by a car, which left him with a broken leg that didn’t heal. He served time in prison for grand theft and contracted the AIDS virus, the complications of which took his life in 1995. He was 42.

“We’re a very conservative game,” said Baker, who suggested MLB has its share of gay players because “baseball is a microcosm of our society.” The lesson learned from Burke’s story, Baker said, is “for us to be open-minded and accept a person (for) who he is.”

John Shea is The San Francisco Chronicle’s national baseball writer. Email: jshea@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @JohnSheaHey