The German biochemist Otto Warburg made few friends — not among his fellow scientists, despite his Nobel Prize for unlocking one of the secrets of cancer, and not among the Nazi leadership, who nevertheless let this scion of a famed Jewish family run one of the Reich’s most important biology research centers.

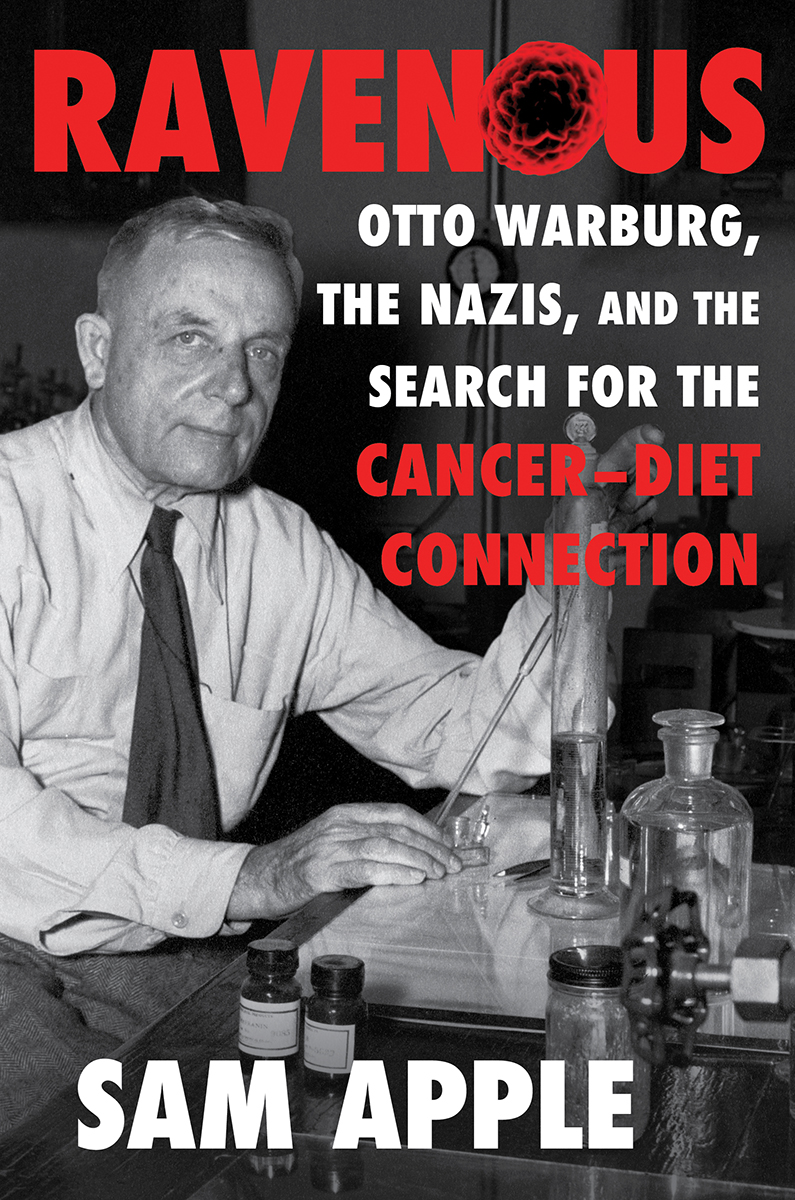

How the brilliant and imperious Warburg (1883-1970) stood up to the Nazis and continued his sometimes lonely pursuit of a cure for cancer is the subject of Sam Apple’s forthcoming biography, “Ravenous: Otto Warburg, the Nazis, and the Search for the Cancer-Diet Connection” (Liveright). It’s a deep dive into the history of cancer research, the anti-Jewish madness and medical quackery that consumed Hitler, and the recent rediscovery of the “Warburg effect” and how it might just explain the West’s cancer epidemic.

Apple is the author of two previous books, “Schlepping Through the Alps” and “American Parent,” and teaches journalism and creative writing at Johns Hopkins University. He spoke to The Jewish Week from his home in Wynnewood, Pa. This interview has been condensed for length and clarity.

I hate asking the “why this book” question to start any interview, but when I remember your first book — about an eccentric Austrian shepherd who happens to sing Yiddish folk songs — I wondered why you would want to spend so much time with a person as unpleasant as Otto Warburg.

I came to the topic of cancer metabolism before I came to Warburg. I was interested in the science, but it really wasn’t until I came across Warburg that I decided to write a magazine article, and then a book. He was an awful guy in many respects, but he was a genius, and he was an eccentric and I, you know, I’ve always been attracted to those kinds of characters.

Place Warburg in his time, which is the first part of the 20th century. Germany is a scientific powerhouse and he’s studying plant cells and that eventually morphs into cancer research.

His father Emil was a really prominent physics professor at the University of Berlin, at a time when it was still very unusual for Jews to reach a central position. Einstein really loved Emil. Otto grows up in a household surrounded by some of the greatest minds in the history of science. Somebody described him as having even a religious devotion to science.

The question for him is, what can he do to be a great scientist in his own right and reach the fame of his heroes — Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, the great German scientist who won the Nobel Prize for his studies of infectious diseases? He decides, I think very consciously, that he’s going to defeat the great disease of his time and era, and that was increasingly becoming cancer.

We know the Warburgs from his American cousins, the famous Jewish banking family, but by the time you get to Otto it’s two generations removed from his Jewish grandparents.

He’s not particularly close with that branch of the family, but his father grew up Jewish, although, like many German Jews of that generation, assimilated. Although there’s no evidence that Emil rejected his Judaism, Otto grew up with no real Jewish upbringing, and didn’t think of himself as Jewish.

Otto won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1931 for his contributions to cellular metabolism and cellular respiration. What should we know about him in terms of science, especially now, as you write in the second half of your book, his ideas are making a comeback?

Sam Apple (Liveright)

Because his father’s a physicist and Einstein is one of his heroes, he views everything through the lens of energy. In 1923 he makes this fairly remarkable discovery that cancer cells are overeating — eating in a way very different from other cells. That leads to a lot of scientific interest about the connection between metabolism and cancer, but after World War II, his ideas largely began to disappear.

Because of his record during the war? Otto chose to stay in Germany as the head of his fiefdom, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Dahlem, when so many other scientists, Jews and non-Jews, were leaving either out of self-preservation or to protest the Nazi regime.

There are a number of reasons. One is that people detest Warburg. He wasn’t a likable guy, in many respects, and he did himself no favors by making sort of extreme statements saying his own work was all you needed to know about cancer and the rest is garbage.

He was a tremendous narcissist. One example: He didn’t want to be photographed with other scientists out there, including Nobel Prize winners. He was brilliant and he thought of himself as above everybody else. He had an aristocratic personality.

A bigger factor was the genetics revolution that took hold in the late 20th century. As they began to understand DNA and cancer mutations, Warburg’s study of the energy reactions began to seem very unimportant.

He was a patriotic German and served in a famed Prussian cavalry during the First World War. Was he a Nazi sympathizer?

He hated the Nazis but for not entirely the right reasons. He stood up to the Nazis when they came to his institute, and basically screamed at them, saying, “I’ll burn down this institute before I let you interrupt my work.” He wasn’t particularly worried, however, about what they were doing to everybody else. He was happy to just sort of be alone in his institute.

You write that 2,600 scientists had left the country, especially but not only Jews and half Jews and quarter Jews like Warburg (as the Nazis saw him). And yet despite his Jewish ancestry he manages to survive, and the Nazis let him stay on. How does he pull that off?

When I grew up I learned in Jewish day school that the Nazis defined a Jew as someone having one Jewish grandparent. Warburg had two Jewish grandparents. But it’s more complicated than that. In the initial racial regulations of 1933, there were exceptions — for example, if you had served in World War I. And restrictions only applied to people in the civil service and government positions. It really came to a head in 1935 when a lot of Nazi officials were frustrated that so many people were sort of skirting the regulations and that the definition hadn’t been fully worked out. In 1935, they passed the Nuremberg laws, which were meant to crack down on Jews and also provide some clarity as to who’s a Jew and who’s not.

It’s eerie and macabre how, in a country known for its science, Hitler tried to bring fake scientific precision to deciding who was and wasn’t racially a Jew.

There are different regulations according to your parentage, so someone like Otto, who is considered a “first degree Mischling,” or mix-ling, was sort of in the middle. Mischlings were assimilated into German society, went to German churches and their relatives weren’t Jewish, and Hitler was savvy enough in the early days, when Germany still cared about its international reputation, to see that cracking down on them might not be so easy. But as things progressed and particularly after the start of World War II, there was no more political need to protect the Mischlinge people. Hitler hated them especially because they were the living embodiment of what he detested: the intermingling of Jews and Aryans.

In January, 1942, after the second “final solution” conference, Warburg’s status became much more precarious. I believe the preponderance of evidence that it really was the cancer research that saved him.

You write how cancer was both a personal fixation of Hitler’s but also a national fear.

(Liveright)

There’s a tremendous amount of evidence that he was fixated on cancer more so than other diseases. And it makes sense because he lost his mother to breast cancer. There is this phenomenally strange story about a Jewish doctor coming in to care for his mother and young Hitler, by the doctor’s side, telling him to try whatever he can to help his mother. He ends up giving her these terrible, painful treatments and he later described Hitler as the most distraught person he’d ever seen.

But cancer was a very large part of Hitler’s hypochondria. He was constantly talking about the research, spouting off nonsensical theories about cancer and trying a lot of dietary therapies. I don’t have clear proof that Hitler was directly involved in Warburg’s case, but there’s a lot of things pointing to it. On June 21, 1941, when the Nazis would launch Operation Barbarossa, the biggest military operation in history, there’s a conversation between Hitler and Goebbels and they’re talking about cancer research. Warburg had applied for what they call a German “blood certificate” to have his status, you know, upgraded, so I think it’s very likely that Hitler personally intervened to [protect] Warburg.

Hitler also uses cancer as a metaphor for Jews, and the real and fake science gets mixed into his theories of how cancer itself is a symptom of a society that’s allowed itself to be degenerated.

Hitler used the metaphor all the time. You can find it in “Mein Kampf” and his various speeches. In Hitler’s case, the connection between Jews and cancer was more than a metaphor. It was much more a literal connection in his mind. He was worried about cancer and he was worried about Jews. The historian Robert Proctor calls Nazism a national hygiene experiment inflicted on the Jews.

Warburg, of course, wanted to literally conquer disease and Hitler, in his own mind, was attacking disease by lumping Jews into that same category.

Amazingly, Hitler at one point described himself as the Robert Koch of politics. I was struck by the fact that both Hitler and Warburg saw themselves in the image of Robert Koch. Warburg, of course, wanted to literally conquer disease and Hitler, in his own mind, was attacking disease by lumping Jews into that same category.

They were two narcissists born of the same generation, both trying to emulate this heroic German scientist, but one doing it in a rational way and the other doing it in the most monstrous way imaginable.

Warburg was a gay man and had a life-long male partner, which under the Nazis would have been another mark against him. But it wasn’t a deeply held secret exactly.

It’s kind of amazing that he survived, not only as a Jew or first-degree Mischling, but also somebody who’s very clearly homosexual. He and his partner lived in the same house, traveled together, they were inseparable. At one point it was clear that he had been turned in or someone had written a letter to Nazi authorities accusing them of homosexuality, among other crimes. In the same way that he refused to let the Nazis interfere with his science, he wasn’t going to let anybody interfere with his homosexual lifestyle.

You suggest Otto stood up to the Nazis only to the degree that they were going to affect him personally. What was his record in terms of protecting other Jewish scientists? Did he have any empathy for perhaps Jews in his lab, or did he have opportunities and punted?

It’s a little bit of both. He did try to protect a few people, particularly inviting Hans Krebs and other famous biochemists to come work at his laboratory as a way to protect them. There was a guy named Erwin Haas in his laboratory who he protected because he valued his science, but there was another young Jewish researcher who he let go in 1933, seemingly under pressure. He tried to find a position for him in the United States, he wasn’t totally unsympathetic, but he was no champion of the Jewish people. I got the impression that he was worried about himself. And in fairness, like many people he really believed that the Nazi insanity was going to die out after a year or two.

A cousin of Warburg’s said he wrestled every day with, you know, should I stay or should I go. And when I read the stories of all these people who had fled, it really struck me that so many of them were not happy in places where they felt like outcasts. They lost all the prestige they had in Germany. Warburg knew himself and knew that he would have been miserable had he left. He knew himself well enough to know that he needed his castle to feel like an emperor.

There is an ethical debate about Nazi science and whether society can derive a benefit from their inhumane experimentation. Is there any indication that Warburg’s science is tainted?

I don’t think there is. After the war, because he hadn’t left, some thought he was a Nazi sympathizer, but I don’t think that they thought he was actually working on behalf of the Nazis. It is true that after 1942 his institute was reclassified as a war institute, but that only allowed him additional protections to continue his cancer research.

What is Warburg’s legacy in Germany?

In the immediate post-war period I think the new government actually wanted to sort of highlight his career and say look, there’s a Jew who survived. As it became clear that his science was falling out of fashion, he was sort of disregarded in Germany as well. But there is still an Otto Warburg medal that goes to German scientists and the institute is now known as the Otto Warburg House.

Why is it important for people to understand who he was and what he was part of?

There are a few different models of how cancer progresses, and you can focus on the genetic impact on mutations in the DNA, or you can focus on the metabolic angle. Both are clearly relevant, but what Warburg said until the end of its life was: It’s metabolism, metabolism, metabolism, and everybody forgot about that in the late 20th century. And in the last 20 years or so there’s been a huge rediscovery of cancer metabolism and the way that a cancer cell produces energy. It’s absolutely fundamental to cancer. I think he has been redeemed really.

One example you give is that “the path from the refined sugar added to our diets to insulin resistance, and from insulin resistance to cancer, is now well understood and based on widely accepted science.”

My larger goal in this book was to try to investigate a mystery, which is why cancer has become so much more common since the middle of the 19th century, and my ultimate answer is that it’s connected with the sugars in our diet and how they leave us with higher levels of the hormone insulin, which helps cancers grow and overeat in the way that Warburg discovered. Warburg didn’t get the whole story right, but insofar as he focuses the picture of cancer on metabolism he is very much at the center of this 200-year mystery.