According to Bradley Schurman, author of The Super Age: Decoding Our Demographic Destiny, humanity has embarked on an unprecedented demographic shift that will forever change the world as we know it.

How we respond will determine how we address work, what growing older looks like, and answer questions about equity in a new protean age.

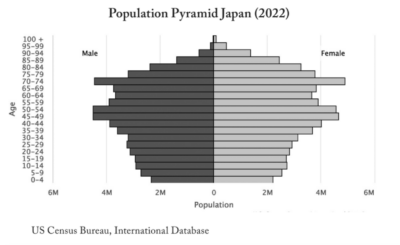

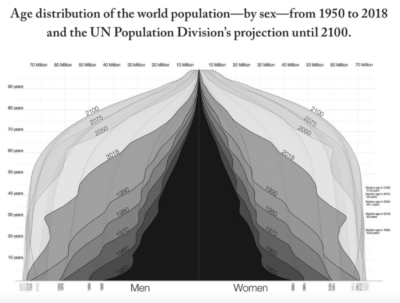

For over 300,000 years, or about as long as humans have walked the Earth, the population looked something like a pyramid, with a broad base of the very young, tapering off as people succumbed to disease and death. For hundreds of thousands of years, the old were few.

But over the last couple of hundred years, the pyramid began to change shape with advances in infant mortality. With food safety, proper nutrition, clean water, and the near elimination of child labor, humans had a much greater chance of becoming adults.

“If you can get a kid from birth to adulthood, they’ve got a pretty good chance of making it to old age — a surprisingly good chance,” says Schurman.

Add in vaccination, medical advances, physical fitness, and fewer causalities of war, and suddenly, relatively speaking, people are living a remarkably long time. The average life expectancy around the world was 73 in 2022.

At the same time, advances in education and the standard of living mean people are having fewer children.

That means the pyramid is squaring — rapidly. Fewer births, fewer deaths, and over a short amount of time to come, fewer people in general. “We just passed eight billion three weeks ago,” says Schurman. “The global population will likely tap out around 10 billion, stop growing and actually go into decline shortly thereafter, sometime this century.”

Welcome to the Super Age, a United Nations designation that defines societies or nation-states where one out of five people are over the age of 65. Japan reached the Super Age in 2006. Several countries in Western Europe have, including Italy and Germany. The United States, Canada, several Latin American countries, and Mexico are well on their way.

Imagine a place where more women are 70-75 than any other population segment. That’s Japan today.

So what does this demographic earthquake mean for the LGBTQ+ community? In Part 1 of a two-part interview, Schurman talks about a toxic Alter of Youth, a shrinking China, and how to live to be 122.

How will the Super Age impact queer people?

The book was written from a 30,000-foot view of society. I’m a gay man, but the narrative can’t fully center around LGBTQ. If it did, that would be its own book. But there are specific trends that are unique to us as a community and specific hurdles that we have to get over.

I grew up in an era where the AIDS crisis was everywhere. As a white gay man born in 1977, my life expectancy was about 40. And this is where it gets to the realities of longevity and the fact that longevity can be really valuable. Today, I’m a 45-year-old gay man, married, happy family, healthy, HIV negative thanks in large part to drugs like PrEP and interventions like condom use. My life expectancy now is closer to 80. We’re talking about obviously major breakthroughs in science and, of course, social behaviors, but my life expectancy has doubled in my lifetime. Pretty cool. That’s a really remarkable thing to live through.

Now, if you’re a trans person of color, you’re not as lucky. The general consensus is that the life expectancy for trans women of color is about 35. That’s awful. And that’s because they’re still, in many ways, outliers from society, despite the significant advances that have been made in understanding and acceptance. They have a harder chance of keeping and maintaining a good job, for example, certainly one that pays well. There are the pitfalls that other marginalized groups face: drug use, or diseases of despair, as we call them, which is everything from alcoholism to suicide. They just hit this group proportionally hard, and they’re part of our community. So if we don’t address these inequities within our own community who are we to say that we are one?

And I speak, of course, from a position of privilege, because as a white gay cisgender man, we now earn the most of any demographic group in the country. The LGBTQ community really is diametrically opposed in terms of what we earn, how we live, what our life expectancy is. It all adds up to a really shocking narrative that very few people understand and even fewer people are willing to talk about.

What are some of the big demographic trends happening worldwide now?

Next year is the big year for China. Not only are they in population decline, but they actually fall to the No. 2 spot in population size, following India, next year. And it’s the first time this has happened in 250, 300 years, that they’ve been the second largest country, and it’s going to be a real psychological blow to that nation. And then when you look into long-term trends, assuming nothing really changes — and that’s not the perfect way to look at things — but their trajectory right now has the population essentially halving itself by the end of this century. So 1.3 billion people become 770 million people. That means by the end of this century about 300 million people will separate the United States and China in terms of aggregate size.

What stands out among demographic trends in the United States?

The fact that 76 million boomers were born, and 69 million of them are still alive today, is nothing short of miraculous. And that actually pushes up the average age of the population across the board. It is really remarkable. And frankly, in the 20th century, it’s probably the most remarkable thing that we’ve done outside of getting to the Moon. Because we have never done this before, where we’ve moved what was essentially 300,000 years of life expectancy hovering around 35 to more than doubling it in less than a century.

And there’s really no upper limit, that we know of, to life expectancy, either. The longest-lived person was 122. She passed away a few years ago. That’s the upper limit that we know of right now. But most people that are in demographics, aging, and longevity are in consensus that the first person to live to be 150 is likely already alive.

In the book, you write about the Alter of Youth, a longtime fixation on youth that’s had detrimental effects on the self-image and prospects of older people across society and culture and in the media. Is that inevitably changing as the population grows older?

So we’ve taken this Alter of Youth, this worship of young people to almost an extreme that borders on comical, and I think that you certainly see that show up in our community. I remember growing up in the 1990s and then in the early 2000s, the age segmentation in bars was disturbing, almost like there were un-rectified conflicts that existed there between young men and older men.

Today, my friend group, my chosen family, really, is aged 25 to about 75 within the gay community of Washington, DC, and that’s by design. I wanted to learn about where we came from. Who we are, you know? We’re not just pop songs and pretty things. There’s a richness to our community that I think, certainly through the oral history, really was erased — big chunks that were erased — during the AIDS epidemic. So being able to stitch that together was very important for me. There’s still that tension but it feels like there’s growing mutual respect. That’s an anecdotal observation. I don’t have data to back that up, but it does feel like the community’s a bit more grounded.

I wonder if COVID has anything to do with that — it’s been kind of a leveler.

What I saw in COVID was a coming-together of a community, at least here in the traditional kind of gay ghetto in Dupont Circle. These ghettos at some point become what people in aging call a NORC, a naturally occurring retirement community. And these networks happen everywhere. They’re not just gay communities. What happens is that within these neighborhoods, natural support networks develop. In DC, there’s a restaurant on 17th Street called Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse. It’s been around now I think for 70 or 80 years. Annie’s really is the de facto cafeteria for a lot of men in the neighborhood. You go there, you grab a good meal. It’s well-priced.

When COVID happened and everything shut down, the staff of Annie’s started delivering meals directly to these men’s homes. So, there was this natural thing that just kind of existed, when no one even thought of it and really turned into action during COVID.

And of course, you know, we were witness to other realities, too, that we hadn’t quite been exposed to before. The fact that so many older gays and lesbians really live in isolation. COVID was scary for a lot of people that centered their social life around these institutions within these networks. When they were not able to do that, they became more isolated.

Just as a point of reference, isolation, and loneliness, that has the same health outcomes as smoking nearly a full pack of cigarettes a day. So, when you become isolated it actually is a threat to your health. There’s greater risk of cognitive decline, there’s greater risk of heart disease setting in, obviously a greater chance of suicide. But in these communities that were a bit tighter, the chances of survival were probably a lot higher, as well.

What are some of the ways older LGBTQ+ people can avoid isolation?

Everyone’s situation is unique. However, the risk of social isolation is everywhere and can affect people living in small rural communities, as well as the big cities.

LGBTQ+ people should do whatever they can to develop strong ties to their families, both blood and chosen, as well as the larger community over a lifetime. This includes creating an age-diverse set of friends, because different generations are less likely to compare each other, and there’s more space to be authentic and offer support.

For those who have lost their network, it’s important to connect with others in person, stay active, seek support, and stay engaged. If you’re feeling alone and would like to reconnect to the community, you should reach out to your local LGBTQ+ center or SAGE, the LGBTQ+ senior advocacy group.

You mention Annie’s Paramount Steak House, which is an excellent example of the community taking care of its own. How do you suggest we formalize these kinds of relationships and programs so they’re permanent and not just ad hoc?

At the end of the day, we need formal and informal spaces, as well as support networks to thrive in later life.

There are a growing number of LGBTQ+ community centers that’ve developed formal programs and resources for LGBTQ+ elders. SAGE offers great resources, too. And the Village to Village Network could be a great model for LGBTQ+ communities across the United States.

###

Check out Part 2 of our interview with Bradley Schurman tomorrow.