Late in the evening on September 30, 1955, screenwriter William Bast sat at his typewriter in his cramped L.A. apartment surrounded by suitcases, banging out a movie outline. The next morning, he planned to carry those suitcases out to Sherman Oaks, where James Dean, his best friend and onetime lover, had invited him to move in together in a large rented house. As Bast told the story decades later, after a long, confusing courtship, full of starts and stops, denials and doubts, Dean wanted them to live together as partners and lovers, not just as friends. Around sunset, the phone rang with the news that Dean, just 24, was dead—killed when his Porsche collided with another car in the California desert. Bast dropped the phone and fell out of his chair, blacking out at the news. For half a century after, he carefully guarded Dean’s reputation, forcefully denying increasingly insistent rumors about the sexuality of the most famous movie star in the world and the idol of millions. In death, Dean would become the perfect celebrity—a silent one—onto whom generations could project their fantasies and themselves.

Death delivered Dean the fame, the love, and the acclaim he struggled to achieve in life. So famous is the photo of him leaning against a wall in blue jeans that he is credited with making jeans the American uniform. More than 65 years later, he remains omnipresent in pop culture. His face sells everything from blue jeans to cars to luxury watches. Photos of him walking through New York or lazing in a cowboy hat hang from countless college guys’ dorm room walls. Generations of young actors have competed to be “the next James Dean.” Lookalikes from the young Martin Sheen to Luke Perry to KJ Apa have dominated Hollywood for half a century. A porn star even borrowed his moniker. Dean’s name appears in more popular songs than almost any other, from David Essex’s classic “Rock On” to the Jonas Brothers’ “Cool.” This spring, Kaskade released another one, “New James Dean.” It’s an extraordinary run at the top for someone who was last alive when Joe Biden was entering puberty and whose body of work consists largely of three movies, only one of which most could even name. His last movie, Giant, hit theaters sixty-five years ago this fall.

Pop culture has endlessly reimagined James Dean from the moment he died—he is straight, bisexual, and gay; sensitive and aggressive; misunderstood and manipulative; victim and predator; the best of us and the worst. As new information slowly emerged over the decades, and social attitudes changed, so, too, did the mix of man and myth passing under the “James Dean” name. Only now, with a new generation rejecting old assumptions about gender roles and sexuality—one in six members of Gen Z self-identify as queer, according to a recent Gallup survey—is it possible to see James Dean as he really was. We can see just how much he, more than any other star of the twentieth century, pointed the way toward modern masculinity. And we can see how heavily previous generations censored and censured his legacy to try to tame its radical potential.

Get unlimited access to decades of Esquire’s Hollywood coverage with Esquire Select.

To write about him now is to describe Gen Z seventy years early. A recent study by the ad firm Bigeye found 50 percent of Gen Z describe traditional gender binaries as outdated, and James Dean had already blurred that line in the oppressive heart of the 1950s. He loved both sports and theater, motorcycles and making art. He was self-centered and narcissistic but befriended marginalized people. He was arrogant but wracked with self-doubt. He took countless selfies in the mirror and performed outrageous stunts for the midcentury version of likes. He wasn’t afraid to cry. On screen, he could convey thunderous emotion with a glance, his performances erupting with tears and screams and howls, a raw vulnerability few young men had ever seen someone their age express. To his teenage admirers, he represented freedom. To his adult detractors, he was ornery, unpleasant, and effeminate. Pauline Kael, then a rising film critic, complained in 1955 that watching him was like stumbling onto the vulgar eroticism of homosexual cruising grounds—“grossly explicit,” too indulgent of boys and their “autoerotic” fixations. Unconsciously, she intuited something hidden and recoiled.

The trouble, from the beginning, was that James Dean wasn’t straight.

In the summer of 1951, Dean, just 20, met and moved in with a much older man, Rogers Brackett, whose bed he shared. “This guy’s a fairy,” a college friend told Dean after meeting the cosmopolitan Brackett, according to Ronald Martinetti’s 1975 biography of Dean. “I know,” Dean replied, worried that others might think the same of him. He lied and told friends and his agent that they had separate beds. It didn’t matter, though. Powerful people made their assumptions. After Dean acted in a live TV broadcast in 1952, the director told him there might be more parts for him if Dean would let him suck his cock. He knew a refusal might end his career, so Dean focused all his attention on a fly crossing the ceiling until it was over. He later said these acts—and there were several, with different powerful men—made him feel like a whore. “It’s no big deal,” Bill Bast recalled him saying, but years after he felt only anger. Too often, his negative experiences erupted in rude, aggressive, or dangerous behavior, what Bast suspected was Dean’s way of taking revenge on a society that wronged him.

The Hollywood rumors started as soon as Dean made the papers, whispers that he was bisexual or gay. His studio, Warner Bros., promoted him alongside Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter, two closeted gay men, as their most eligible bachelor. He burned through a series of short, intense, and tempestuous relationships with women that were often more emotional than sexual, and had furtive encounters with men that were often more sexual than emotional. Much ink would be spilled over the years trying to pin down his sexuality—straight, bisexual, gay, asexual all found their advocates—but he resisted labels, not least because the labels were tied up in bigger questions of masculinity and manhood. In those days, “homosexual” was synonymous with a campy, effeminate stereotype he couldn’t identify with. After all, he played basketball and raced cars. “I’m not a homosexual,” he told a reporter who asked if he was gay, “but I’m not going through life with one hand tied behind my back.”

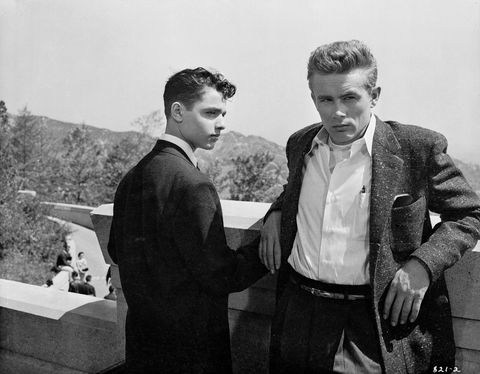

In 1955, on the brink of superstardom, Dean defied the studio censors at Warner Bros. In the heart of the homophobic ’50s, he and director Nicholas Ray quietly weaved a queer love story into his most famous film, Rebel without a Cause, a movie filled with questions about what masculinity meant in the postwar world. Dean advised his costar, Sal Mineo, to play up his character Plato’s attraction to Dean, which he reciprocated with knowing looks. Dean ended the film weeping hysterically over Plato’s death, a lover’s lament. Generations of queer men saw hope in cinema’s first sympathetic depiction of same-sex teenage love, and its only such depiction for more than a generation, but few straight viewers noticed for half a century. Even the National League for Decency, a Catholic moral watchdog, rated the film “unobjectionable.” Roger Ebert only acknowledged its homoeroticism in print in 2005, and minimally at that. Viewers did, however, notice Dean himself, and the more they learned, the more uncomfortable they became.

The moment when he died shattered his life as much as his body. Like a fractured reflection in a broken mirror, those who later sought to find the “real” James Dean could only piece together a distorted image from fragments that never quite fit. Reading through the mountain of biographies and memoirs of James Dean is to enter something like a comic book multiverse, where a single soul is fractured across a thousand realities. Each version of the man shares a few basic facts—the same birthday in 1931, the same loss of his mother as a child, the same adolescence on his relatives’ Indiana farm, and the same rapid rise through television, Broadway, and movies—but no two writers ever encounter exactly the same man. As journalists and authors attempted to forge a biography from the short life and scant documentary evidence, James Dean became hopelessly intertwined with the characters he played on screen. They needed some explanation for the power of his image. Each writer projected as much of himself—and they are mostly all men—onto Dean as they captured of the real man. In one of the most popular Dean biographies, David Dalton, a Rolling Stone co-founder taken with the New Age, even filled the gaps with pagan mythology and concluded in all seriousness that Dean was an avatar of the Egyptian god Osiris.

Across America, teenagers and young adults reacted to Dean’s death as though they lost their best friend. Girls fainted at the news. Boys choked back tears. Many refused to believe him gone. Hundreds of fan clubs sprang up, and the dead star received five thousand fan letters per month. It’s hard to imagine now just how deeply they loved the person they saw on the movie screen. The unprecedented national grieving defined what would become America’s new love affair with adolescence and endless youth. Teens flocked to Dean’s next film, Rebel without a Cause, released just weeks after he died, and boys saw in its disaffected teenage hero a reflection of themselves, someone who also struggled to be a “real” man, who nevertheless could be both cool and vulnerable. Suddenly, teenage boys had both power and purpose and a liberating role model. And their parents’ generation hated it, not least because they worried about their boys becoming like him—sensitive, unmanly, code for queer. And they had the power to do something about it.

Warner Bros. made moves to sanitize Dean’s biography, stripping away the problematic parts of his life, sanding off his anger and harder edges, and making his rebel act a commodity, one more acceptable to the parents of teens. A year after Dean died, Ballantine Books commissioned a biography of Dean from Bill Bast, who followed his publisher’s orders without needing to be asked and purged Dean’s life of anything queer to protect the man he loved, even in death. That didn’t stop queer people from seeing in Bast’s biography and in Rebel what oblivious straight audiences could not. The queer playwright W. Somerset Maugham read and understood, as did future gay activist Jack Fritscher. “James Dean was masculine; he was blond; he was hot; he was California; he was American; he was gay,” Fristcher recalled of his teenage infatuation. “I wanted James Dean. I wanted to be him.”

In 1956, Esquire itself scoffed at “The Apotheosis of James Dean,” depicting Dean’s face beneath shattered glass. In 1959 the magazine asked the famed novelist John Dos Passos to write about Dean for the magazine’s fiftieth anniversary. He complained scornfully of the “sinister” Dean’s “thwarted maleness; girl-boy almost,” and mocked teenage boys for dressing and acting like their unmanly idol, all vanity and narcissism and too much sensitivity. They weren’t real men. Teenagers didn’t care, of course. The old men scoffed, but the young men saw a freer, less confining, more honest idea of masculinity. At least for a while. But this was still the 20th century, and as they grew older, they grew less radical.

In the mid-1970s, a quartet of biographies announced Dean’s sexual involvement with other men. Looking back, it’s easy to see how the straight boys who worshiped Dean, now middle-aged men, felt betrayed. They had modeled themselves and their manhood on one of those people. Worse, after the Stonewall Riot signaled the start of the gay rights movement, openly queer men like culture critics Parker Tyler and Jack Babuscio claimed Dean as an icon of gay liberation. His picture hung in gay bars. Gay magazines and newsletters discussed his sexuality, and San Francisco’s first leather bar, Fe-Be’s, commissioned a statue of a biker that remodeled Michelangelo’s David as a leather-clad James Dean.

Suddenly there was market for posthumously punishing Dean for his betrayal of heterosexual manliness. A generation of writers, both straight and gay, began claiming he was a sexual predator, a sociopath, someone who should be shamed for his sex life, which they wrongly envisioned in increasingly baroque ways. Biographer Venable Herndon alleged that Dean had been a gay sex worker for whom no act was too degrading or too extreme. In Hollywood Babylon II, Kenneth Anger depicted him burning his flesh with cigarettes during what Anger described as sexual self-punishment. Just five years ago, biographer Darwin Porter improbably alleged Dean was the submissive in a master-slave relationship with Marlon Brando that shaded uncomfortably into abuse. In his recent study of Dean’s movie Giant, the late Don Graham envisioned Dean as a sociopathic but aggressively straight predator systematically using sex to entrap powerful older men. This summer, in nis new novel Widespread Panic, aging L. A. Confidential author James Ellroy still depicted Dean as a villain, a sex worker and pornographer, an amoral androgynous sex fiend. “I’m really kind and gentle,” Dean once wrote.

But no one reads books, not anymore. Few people have heard much about what’s in them. Outside of the LGBTQ+ community and academia James Dean’s sex life is still news, half a century late. Dean believed in the power of image, and Hollywood and Madison Avenue have long sold a different James Dean to the public, the smoldering, straight stud ripped right from 1950s Warner Bros. publicity campaigns. That James Dean, the one seen in sweeps-week TV biopics and glossy campaigns for brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Montblanc, has been reduced for seven decades to an image, a celluloid saint, silent and safe. To an extent it was understandable. Advertisers and producers had often faced major backlash if they used queer people to advertise to straight consumers, and James Dean remains one of America’s best-paid dead celebrities, still taking in as much as $8.5 million per year, according to Forbes’ recent annual rankings.

The irony is that the image of James Dean the cool rebel was a purposeful performance, the photographs passing for the man as incomplete as the shards of biography that mixed with his film roles and passed for his life. The real, complicated, insecure, nerdy, queer person behind the image, however, remains dangerously, shockingly modern, a twentieth-century man fighting to have a twenty-first century life. It’s past time we let him.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io