Gerald Davison, a USC professor of psychology, had a secret teaching tool to use in some of his classes in the past year: a movie starring himself

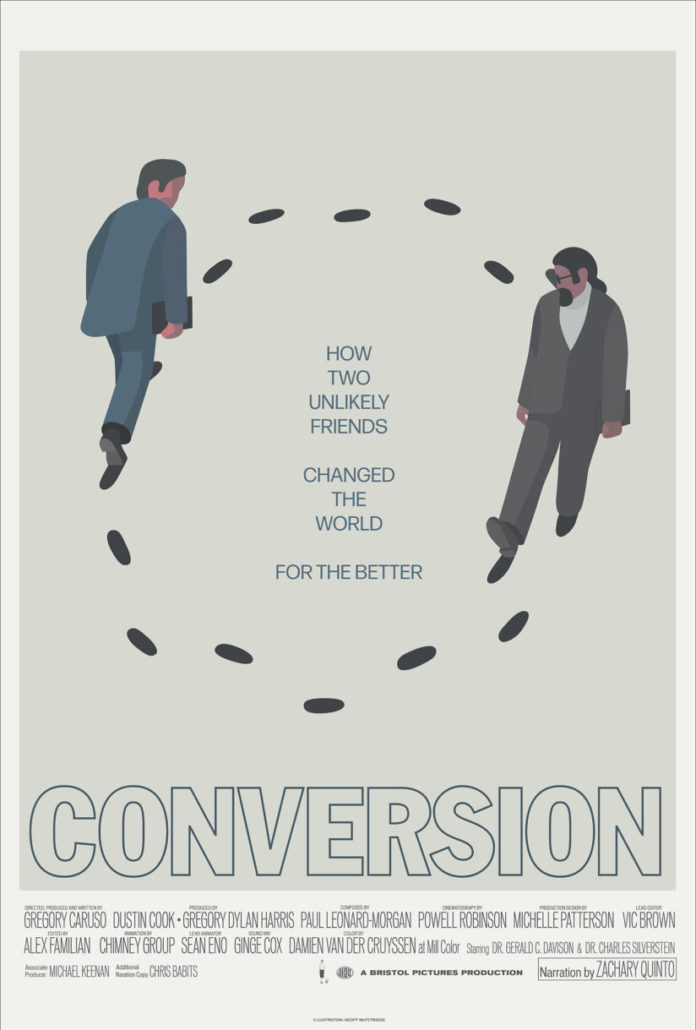

The movie was an early cut of the documentary Conversion, which tells the story of how Davison went from being a young psychologist practicing a form of conversion therapy on gay men to publicly speaking out against the practice at a national convention before about 1,000 of his peers.

Conversion, directed by USC School of Cinematic Arts graduate Gregory Caruso, was recently released on various streaming platforms. It was screened at several film festivals last year and won best documentary feature at the New Renaissance Film Festival in London.

“I want all sorts of people to see it — as many as possible,” said Davison. “A lot of people — both straight and gay — have told me they have wept during the film, and I have, too. Gregory wove it together and told a very compelling story that has a lot of cinematic punch to it.”

A fateful meeting that would change attitudes toward gay conversion therapy

The film tells the story of how two unlikely friends — straight psychologist Davison and gay activist Charles Silverstein — changed the psychology world for the better after first crossing paths 50 years ago at a convention of the Association for Advancement of Behavioral Therapies in New York City.

Davison was just 33 years old in 1972 when he was elected president of the association, which is now known as the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. He presented a workshop at the convention that year on “new and more humane” ways the help gay men change their sexual orientation that didn’t involve any kind of punitive aversion methods such as using painful electric shocks applied to the fingers.

In attendance was Silverstein, then working on his doctorate at Rutgers University, who had been publicly critical of Davison for using a conversion therapy on gay patients that involved Playboy magazines.

“I published one paper with this so-called Playboy therapy in 1968,” Davison recalled. “I was trying it out with the gay patients I was seeing, maybe about a dozen cases. I was basically trying to teach gay guys how to be straight, learn how to talk to women, and I was banging my head against a wall.”

Davison knew Silverstein was there: Before the start of the session, the outspoken student had been passing out flyers to his own symposium, set for the convention’s final day.

Silverstein strode up to Davison and introduced himself, handing Davison a flyer. Despite their opposing views, both men remained cordial; Davison accepted the flyer, stuffed it in his pocket, then didn’t think much more about it. But after missing his train on the final day, he decided at the last minute to attend Silverstein’s talk. It turned out to be a fateful, career-changing decision.

Charles Silverstein (left) and Gerald Davison share a moment in Conversion.

He recalls having “an intellectual and emotional epiphany” he likened to “a bolt of lightning” when he heard Silverstein at the symposium say these words: “To suggest that a person comes voluntarily to change his sexual orientation is to ignore the powerful environmental stress, oppression if you will, that has been telling him for years that he should change.”

Davison never felt the same way about conversion therapy again. He would go on to make a landmark presidential address to the Association for Advancement of Behavioral Therapies in 1974 that detailed his objection to conversion therapy under any circumstances.

“He opposed trying to cure gay people on moral grounds,” said Silverstein. “That was an extraordinary statement, and no one else had said that, including me. He was incredibly brave.”

Davison even quoted Silverstein’s 1972 symposium remarks toward the end of his speech, which he concluded by adding: “Even if we could effect certain changes, there is still the more important question of whether we should. I believe we should not.”

Davison fully credits Silverstein with helping him to realize “it’s not whether you can do it, it’s whether you should do it. It occurred to me that I shouldn’t be doing it, and my colleagues were all wrong.”

Davison has been at USC since 1979, with appointments at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology; he has continued to argue against conversion therapies in scholarly publications, research and teachings. His landmark 1974 speech was later published in a leading clinical journal.

“I was really criticized, sometimes very harshly, by friends of mine who were saying, ‘You’re a great guy, but you’re making a terrible mistake,’” Davison said. “But it helped a great deal to get colleagues to think about what they were doing when they were treating a person and what’s behind it. Are we really helping them or just acting like society’s cops and trying to force social conformity?”

Filmmaker discovers Davison’s story on gay conversion therapy

One night in November 2018, Caruso heard an episode of a podcast seriescalled UnErased: The History of Conversion Therapy in America that featured an extensive interview with Davison.

“I was inspired and motivated to make a visual form of that podcast after hearing it,” Caruso said. “It was very moving. I thought it was an important story to be told, especially in our divisive times.”

[Editor’s note: Gregory Caruso is the son of USC Trustee Rick Caruso, a candidate for Los Angeles mayor.]

The film’s release comes at a time when a wave of anti-LGBTQ+ laws are being proposed and enacted around the United States. These include Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law, which bans classroom discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity from kindergarten through third grade.

I think the movie certainly will move a number of people — but not the politicians who are pushing to take away the rights of gay people.

Charles Silverstein, gay activist

“I think the movie certainly will move a number of people — but not the politicians who are pushing to take away the rights of gay people,” observed Silverstein, founding editor of the Journal of Homosexuality. “Those laws are just going to hurt people.”

Davison is proud of his role in history but accepts that, even 50 years later, some people continue to view homosexuality as something to be “cured.”

“There are some folks who, because of their personal beliefs, just can’t take it,” he said. “I don’t think they will ever be persuaded.”

Lasting friendship between two experts

Caruso knew his movie also had to be about the friendship Davison and Silverstein had maintained over the years.

“What really grabbed my attention was the relationship between Jerry and Chuck,” the filmmaker said. “Chuck’s openness to go up to Jerry and introduce himself and not write him off, and Jerry’s openness to change his mind and listen and then admit that he was wrong. All of those things resonated with me. They were so confident and true to who they were. They were not only courageous, they were smart and I think definitely ahead of their time.”

Caruso brought the men to a Los Angeles soundstage in early 2019 to film their interviews for the documentary. Though they had kept in touch by email and an occasional phone call, they had not been together in the same room for more than 35 years.

They embraced and then set about reliving their story.

“We sort of picked up where we left off,” Davison said. “It was as if no time had passed.”

Both men hope the film is widely seen so that people on both sides of these issues will learn from the past.

“All these events happened in the 1970s and people have forgotten about it,” Silverstein said. “Both straight and gay people don’t know about it because it’s not taught. Producing a documentary like this reminds them of what it was about.”

More stories about: Alumni, Cinema, Diversity Equity and Inclusion, Faculty, LGBTQ