Growing up in a religious household, Mandy Moore wasn’t exposed to bisexuality until coming across Shadowhunters’ character Magnus Bane in high school. Looking back at her childhood, Moore said being introduced to the LGBTQ community earlier could have changed the course of her life.

“I can’t imagine how different my life would have been if I’d even known that there were other options besides being gay or straight,” she said.

Moore, a graduate student and instructor at UF who specializes in television, children’s media and fandom-culture research, is not the only one who found her identity through television. For many members of the LGBTQ community, representation in different entertainment mediums can play a crucial role in personal development, especially in children.

Media monitoring organizations like GLAAD tracked LGBTQ representation in the general entertainment industry for 25 years. The growing space for LGBTQ stories on kids and family programming begs the question of whether the public can place a level of responsibility on influential children’s media outlets to produce inclusive content.

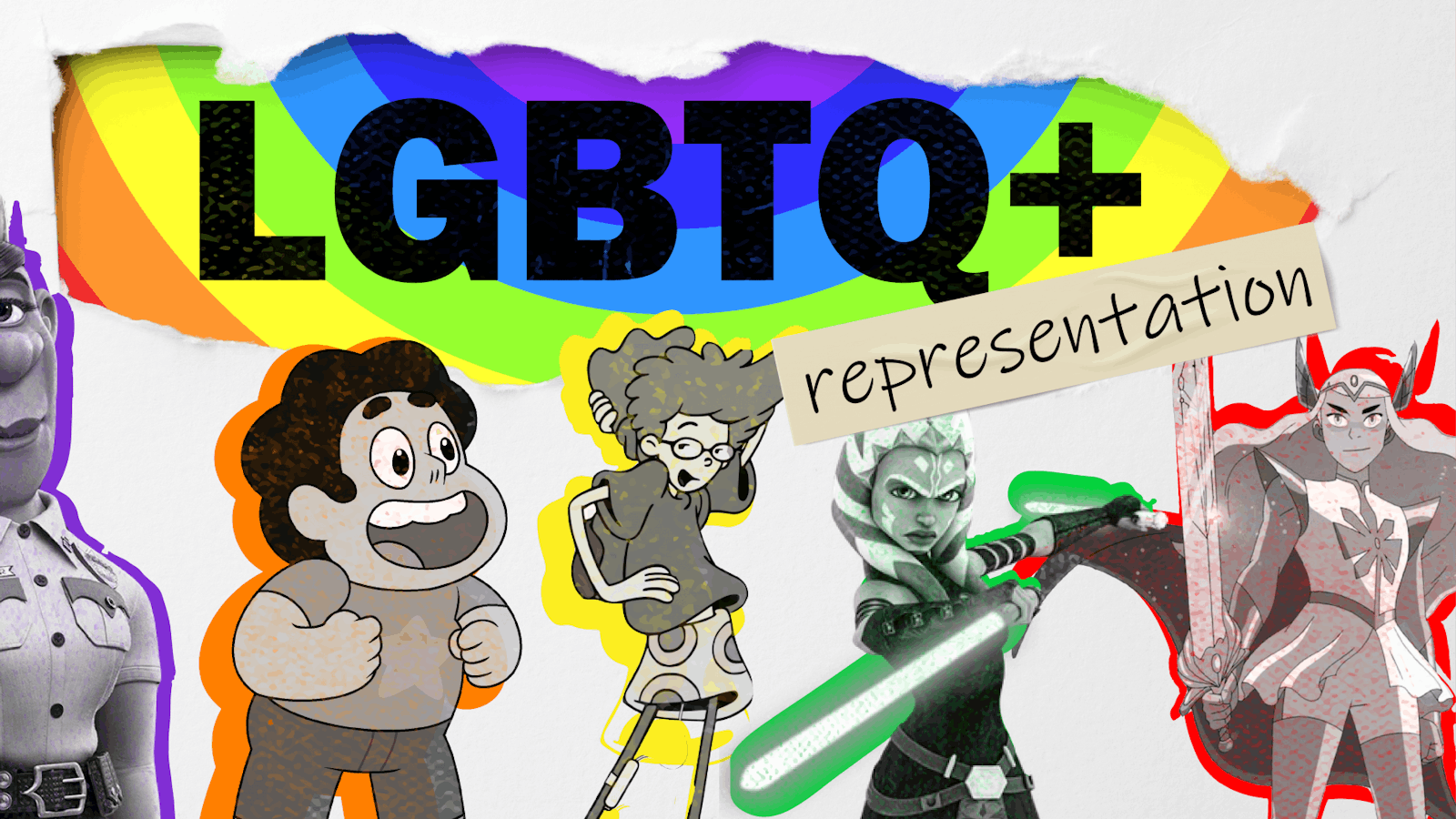

Since the 2010s, kid-friendly media saw a jump in progressive animations introducing openly LGBTQ characters, such as Cartoon Network’s “Steven Universe” and DreamWorks’ “She-Ra and the Princesses of Power.” These shows received awards and nominations specifically for their LGBTQ representation.

Although Disney’s 2019 Corporate Responsibility Report mentions its commitment to “championing diversity and inclusion,” the company continues to face heavy criticism for utilizing queer-coding, queerbaiting and tokenism techniques in their films.

Examples include only adding queer characters into background shots and/or only providing them with limited storylines, such as in “Toy Story 4” and “Onward.”

With a growing openly LGBTQ population, Moore said full representation in children’s entertainment is necessary to accurately depict today’s society.

“Just having gay characters in the background can be helpful for normalizing things, but if you never show queer people in their full humanity, that’s not really representation,” she said.

Kevin Cooley, a doctoral candidate at UF, works in film and media studies, animation and comics, and queer theory. He said cartoons made by queer women, such as “Angela Anaconda” (1999) and “Pepper-Anne” (1997), helped him unlearn the rigid conception of gender and desire he’d inherited from the heteronormative world.

“Animation, cartooning, visual culture, illustrations, video games, and fantastical novels are not just ‘escapes’ from the dreary real world children inhabit,” Cooley wrote in an email. They are chances to re-write the mythologies we teach children, and to broaden the possibility for what their own identities can be.”

Like Moore, Jules Catuogno, a 24-year-old UF psychology alum, said the first memorable queer characters they saw were from TV shows they watched in high school. While Catuogno believes children’s media increased its LGBTQ representation, they said corporations will never do enough “due to their nature.”

Enjoy what you’re reading? Get content from The Alligator delivered to your inbox

“The steps that corporations take to show representation often remove many of the radical and revolutionary parts of being queer because they don’t fit into mainstream expectations,” Catuogno said. “They have an obligation to, at the very least, be representative of queer people; however, no corporation is going to do work towards the actual liberation of queer people.”

While publicly praised shows like “Steven Universe” and “She-Ra and the Princesses of Power” were created by openly queer individuals, Moore said issues of tokenism among larger corporations like Disney can occur from lack of representation within the studio’s writing staff.

For Kenneth Kidd, the associate chair and undergraduate coordinator of UF’s English department, growing up watching television and film in the ‘70s and ‘80s meant mainly seeing queer-coded representation from characters who were given stereotypical traits audiences were expected to interpret as queer.

“There weren’t characters with ‘out’ sexualities or alternative gender identities even, but there were eccentric, odd, singular characters with interesting life choices,” Kidd wrote in an email. “‘Pee Wee’s Playhouse’ was one of the first rather queer TV shows for children, but I’d say there was always a tradition of theatricity in some children’s programming.”

In terms of placing responsibility on large influential corporations, Kidd said profits are usually the pressing concern for most children’s media outlets to include LGBTQ representation.

“Things funded with public money have a particular ethical commitment to promote fairness and diversity and equity,” Kidd said. “Corporate media has some responsibility for positive treatments of queer people and people in all their diversity, and they have sometimes taken the lead on this because they are more alert to changes in the culture and the market.”

Cooley said that because corporations can only be counted upon if it benefits them financially, the solution to receiving better LGBTQ+ representation seems to lie in ensuring individuals who identify with the community are infiltrating children’s media enterprises.

“Instead of placing our faith in corporations, we’d have better luck placing it in artists savvy enough to hijack corporate media channels for their massive distribution networks and work within those spaces to create and distribute new and provocative queer media,” Cooley said.

“In short: we can’t count on Disney to queer Star Wars, but you’d better believe Dave Filoni is going to fight as hard as he can for a queer Ahsoka Tano story!”

Contact Brenna at bsheets@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @BrennaMarieShe1.

The Independent Florida Alligator has been independent of the university since 1971, your donation today could help #SaveStudentNewsrooms. Please consider giving today.