No paywall. No pop-up ads. Keep the 74 free for everyone with a donation during our Fall Campaign.

Amid warnings from lawmakers and civil rights groups that digital surveillance tools could discriminate against at-risk students, a leading nonprofit devoted to the mental well-being of LGBTQ youth has formed a financial partnership with a tech company that subjects them to persistent online monitoring.

Beginning in May, The Trevor Project, a high-profile nonprofit focused on suicide prevention among LGBTQ youth, began to list Gaggle as a “corporate partner” on its website, disclosing that the controversial surveillance company had given them between $25,000 and $50,000 in support. Meanwhile Gaggle, which uses artificial intelligence and human content moderators to sift through billions of student chat messages and homework assignments each year in search of students who may harm themselves or others, published a webpage noting the two were collaborating to “improve mental health outcomes for LGBTQ young people.”

Though the precise contours of the partnership remain unclear, a Trevor Project spokesperson said it aims to have a positive influence on the way Gaggle navigates privacy concerns involving LGBTQ youth while a Gaggle representative said the company sees the relationship as a learning opportunity.

Both groups maintain that the partnership was forged in the interests of LGBTQ students, but student privacy advocates argue the relationship could undermine The Trevor Project’s work while allowing Gaggle to use the donation to counter criticism about its potential harms to LGBTQ students. The collaboration comes at a particularly perilous time for many students as a rash of states implement new anti-LGBTQ laws that could erode their privacy and expose them to legal jeopardy.

Teeth Logsdon-Wallace, a 14-year-old student from Minneapolis with first-hand experience of Gaggle’s surveillance dragnet, said the deal could eliminate any motivation for Gaggle to change its business practices.

“It really does feel like a ‘We paid you, now say we’re fine,’ kind of thing,” said Logsdon-Wallace, who is transgender. Without any real incentives to implement reforms, he said that Gaggle’s “seal of approval” from The Trevor Project could offer the privately held company reputational cover amid growing concerns that such surveillance tech is disproportionately harmful to LGBTQ youth.

“People who want to defend Gaggle can just point to their little Trevor Project thing and say, ‘See, they have the support of “The Gays” so it’s fine actually,’ and all it does is make it easier to deflect and defend actual issues with Gaggle.”

Following an investigation by The 74 into Gaggle’s monitoring practices, the company faced swift blowback for its effects on LGBTQ youth. Gaggle’s algorithm relies on keyword matching to compare students’ online communications against a dictionary of thousands of words the company believes could indicate potential trouble, including references to violence, drugs and sex. Among the keywords are “gay” and “lesbian,” verbiage the company maintains is necessary because LGBTQ youth are more likely than their straight and cisgender peers to consider suicide.

But privacy and civil rights advocates have accused the company of discrimination by subjecting LGBTQ youth to heightened surveillance — a concern that has taken on new meaning this year as states like Florida adopt laws that ban classroom discussions about sexuality and require educators to out LGBTQ youth to their parents.

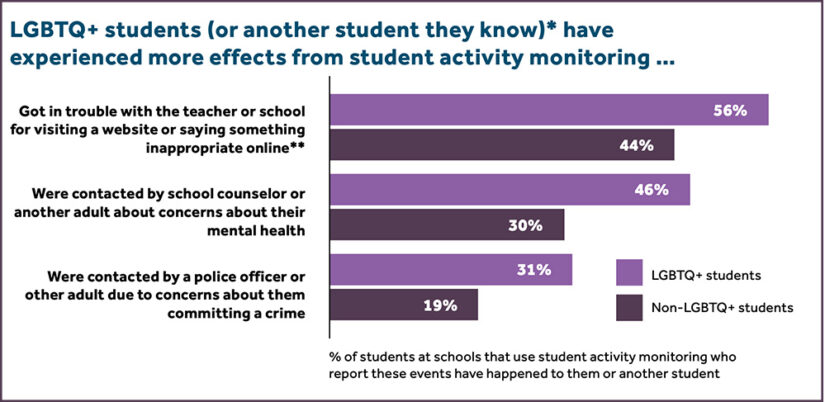

A recent report by the nonprofit Center for Democracy and Technology found that while Gaggle and similar student monitoring tools are designed to keep students safe, teachers reported that they were more often used to discipline them. LGBTQ youth were disproportionately affected.

In a statement, a Trevor Project spokesperson said it’s important that digital monitoring tools keep students safe without invading their privacy and that the collaboration was built on Gaggle’s “desire to identify and address privacy and safety concerns that their product could cause for LGBTQ students.”

“It’s true that LGBTQ youth are among the most vulnerable to the misuse of this kind of safety monitoring — many worry that these tools could out them to teachers or parents against their will,” the statement continued. “It is because of that very real concern that we have worked in a limited capacity with digital safety companies — to play an educational role and have a seat at the table so they can consider these potential risks while they design their products and develop policies.”

But it remains unclear what policy changes have occurred at Gaggle as a result of the deal. Without offering any specifics, Gaggle spokesperson Paget Hetherington said in a statement the company is “honored to be able to align with The Trevor Project to better serve LGBTQ youth,” and that the company is “always looking for ways to learn and to improve upon what we do to better support students and keep them safe.”

‘Faceless bureaucracy’

At its core, the partnership between Gaggle and The Trevor Project makes sense because both work to prevent youth suicides, said Amelia Vance, the founder and president of Public Interest Privacy Consulting. But their approaches to solving the problem, she said, are fundamentally different.

By combing through digital materials on students’ school-issued Microsoft and Google accounts, Gaggle seeks to alert educators — and in some cases the police — of students’ online behaviors that suggest they might harm themselves or others.

“It really is about collecting details that kids may not be voluntarily sharing — information that they may be looking up to learn, to explore their identities, to otherwise help them in their day-to-day lives,” Vance said. At The Trevor Project, “you have proactive outreach from youth who know that they need help or they need a community.”

The West Hollywood-based Trevor Project, which relies heavily on celebrity endorsements and funding from major corporate sponsors including Macy’s and AT&T, was founded in 1998 and reported $29.6 million in contributions in 2020. Gaggle, founded in 1999, does not publicly report its finances. The Dallas-based company says it monitors the digital communications of more than 5 million students across more than 1,500 school districts nationally.

The Trevor Project has also turned to artificial intelligence to train volunteer crisis counselors and assess the risk levels of people who reach out to the nonprofit’s suicide prevention hotline for help. If counselors with The Trevor Project believe a student is at imminent suicide risk, policies direct them to call the police. But it’s ultimately up to youth to decide which information they share with adults.

It’s important for LGBTQ students to have trusting adults with whom they can confide their experiences, Vance said, rather than a system where “some faceless bureaucracy is finding out and informing your parents” about information they intended to keep private.

A recent national survey by The Trevor Project offers troubling data about the realities of the youth suicide crisis. Nearly half of LGBTQ youth said they seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year and 14% said they made a suicide attempt.

This isn’t the first time The Trevor Project has faced scrutiny in recent months for its ties to companies that could have detrimental effects on LGBTQ youth. In July, a HuffPost investigation revealed that CEO and Executive Director Amit Paley previously served as a consultant to Purdue Pharma and helped create a strategic plan to boost opioid sales amid an addiction epidemic — one that’s associated with a threefold increase in suicide attempts among LGBTQ youth.

The group knows firsthand how data can be weaponized. Just last month, trolls on far-right online messaging boards that target the transgender community launched a campaign to clog up The Trevor Project’s suicide prevention hotline.

Persistent student surveillance could exacerbate the challenges that LGBTQ youth face by subjecting them to disproportionate discipline and erroneously flagging their online communications as threats, Democratic Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey warned in an April report.

Nearly a third of LGBTQ students say they or someone they know has experienced the nonconsensual disclosure of their sexual orientation or gender identity — typically called “outing” — due to student activity monitoring, according to a recent report by the nonprofit Center for Democracy and Technology. They were also more likely than their straight and cisgender peers to report getting into trouble at school and being contacted by the police about having committed a crime.

In response to the survey results, a coalition of civil rights groups called on the U.S. Education Department to condemn the use of activity monitoring tools that violate students’ civil liberties and to state its intent “to take enforcement action against violations that result in discrimination.” The letter argues that using the tools to out LGBTQ students or to subject them to disproportionate discipline and criminal investigations could violate Title IX, the federal law prohibiting sex-based discrimination in schools.

Among the letter signatories is the nonprofit LGBT Tech, which has warned about the harms of digital surveillance on LGBTQ people. Christopher Wood, the group’s co-founder and executive director, said The Trevor Project’s partnership with Gaggle could be positive if it’s used to ensure that LGBTQ youth who are struggling have access to help. But once Gaggle gives student information to school administrators, the company can no longer control how those records are used, he said.

“If that information is provided to someone who is not accepting, who has very different views and who willfully brings their political, personal or religious views into the school system, and they are not supportive of LGBTQ youth, then what they’ve done is harm the student,” Wood said.

Yet as schools increasingly turned to student activity monitoring software during the pandemic, The Trevor Project portrayed their growth as an inevitable result of districts seeking “to avoid liability issues.”

“It is our stance that since these tools are not going anywhere, we think it’s important to do our part to offer our expertise around LGBTQ experiences,” the spokesperson said.

The power of trust

In interviews, students flagged by Gaggle said their trust in adults suffered as a result. Among them is Logsdon-Wallace, the 14-year-old transgender student. Before the Minneapolis school district stopped using Gaggle this summer and state lawmakers put strict limits on digital surveillance in schools, the tool alerted district security when he used a classroom assignment to reflect on a previous suicide attempt and how music therapy helped him cope. That same assignment, which included references to his gender identity, was flagged to his parents.

And while his parents are affirming, he has friends who live in less supportive environments.

“I have friends who are queer and/or trans who are out at school but not to their parents,” he said. “If they want to be open with teachers, Gaggle can create a bad or even dangerous situation for these kids if their parents were contacted about what they were saying.”

In The Trevor Project’s recent survey, nearly three-quarters of LGBTQ youth reported that they have endured discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, just 37% said their homes are affirming and 55% said the same about their schools.

Given that reality, just 43% of LGBTQ youth reported sharing information about their sexual orientation with teachers or guidance counselors.

While Gaggle has maintained that keywords like “gay” and “lesbian” can also prevent bullying, Logsdon-Wallace said their approach is out of touch with how students generally interact. At school, he said he’s been called just about every “slur for a queer or a trans person that isn’t from like 80 years ago.” While slurs are common, terms like “lesbian” are not.

“As an actual teenager going to an actual public school, those words are not being used to bully people,” he said. “They’re just not.”

Sign up for the School (in)Security newsletter.

Get the most critical news and information about students’ rights, safety and well-being delivered straight to your inbox.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter