Her husband remembered his Apple Watch had just been updated with an ECG app, so he strapped it to his wife’s wrist. Within minutes the app had detected atrial fibrillation, a major cause of stroke, and the ambulance was called. The woman spent three days in hospital and is now on medication for the condition. She’s also since bought her own Apple Watch.

“They wrote to me, and these kinds of stories really mean something to us,” says Cook, whose Alabama accent gives a warm authenticity to everything he says, even lines he’s almost certainly uttered thousands of times over. “We’ve always felt that technology was meant to enrich people’s lives, and there’s no better example of that than saving someone’s.”

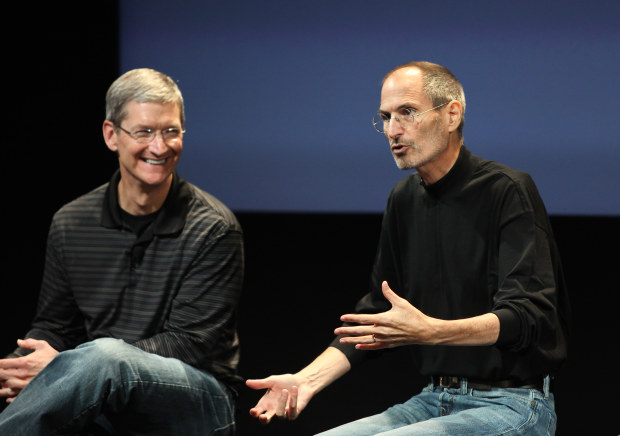

Cook on stage at an event with Steve Jobs in 2010. Getty

It’s a thrilling time to be at the head of a global tech company. Speaking to the Financial Review on the occasion of our 70th anniversary, his first sit-down interview with Australian media, Cook is, as you’d expect, optimistic about how technology will keep making our lives better. He’s excited about artificial intelligence, which is already “all over the current iPhone, iPad and the watch et cetera” but “we’re only at the early stages of what can be done”. AI will take away some of the mundane things we do every day, he says, and free up our time so we can do more of what we love.”

He goes on: “I’m a huge believer in augmented reality. It can enhance our conversations that we’re having, and enhance learning and really amplify the value of technology with people, without it enclosing or shutting off the real world.”

To illustrate, he circles back to an earlier part in our interview, conducted over Webex with Cook in his office in Cupertino and me in my dining room in locked-down Sydney, where we talked about the huge number of Australians who are registered with Apple to build apps using its software; Cook says there are 600,000 of us, coding away.

“I could have pulled up a graph and showed that to you,” he says, moving his hands through the air. And when Cook says “I could have”, it’s a fair bet a huge team of Apple engineers are working to make that exact thing happen, possibly quite soon.

What one does not expect from Cook is how alarmed he has become about the negative forces unleashed by his neighbours in Silicon Valley.

“Technology doesn’t want to be good. It doesn’t want to be bad, it’s neutral,” Cook says when asked about the potential downsides from tech as we move towards the middle of this century. “And so it’s in the hands of the inventor and the user as to whether it’s used for good, or not used for good. And it depends on creativity. It depends on empathy. It depends on the passion of the people behind the technology. At Apple, when we make something, we make sure that we spend an enormous amount of time thinking carefully about how it will be used.”

He makes a point of Apple’s privacy and security features. Features, he says, that derive from the company values laid down by Jobs. Specifically he mentions Screen Time, a tool which helps people monitor whether they’re spending too many hours on their device.

“The risk of not doing that means that technology loses touch with the user. And in that kind of case, privacy can become collateral damage. And conspiracy theories or hate speech begins to drown everything else out. Technology will only work if it has people’s trust.”

Does he think people’s trust has been taken advantage of?

“In some cases the answer is undeniably yes. And I think it’s incumbent on all of us to rebuild that trust.”

Cook’s comments about spending too long on your iPhone may sound facile coming from the boss of the company that makes them, but they represent an important tonal shift. US tech companies, having grown to become some of the world’s most valuable businesses, are turning on each other. One field of battle is the high-stakes lawsuit brought by Epic Games against Apple over its App Store.

Epic, the maker of Fortnite, argues that Apple wields monopoly power by forcing developers to hand over 30 per cent of the price of digital goods and services, such as games and music, sold through the App Store. In Epic’s case, that’s 30 per cent of a sizable chunk of the $9 billion in revenue it earned over two years.

At issue is Apple’s so-called “walled garden”, a carefully pruned and tended system whereby hardware is tightly integrated into its software, giving Apple control over which apps are allowed on iPhones and iPads. Apple says this ensures an environment free from malware. But it also means Apple can push back against its rivals.

The Financial Review Platinum 70 magazine is out on Friday, August 20.

Microsoft (the world’s second most valuable company) has been thwarted by Apple in accessing the App Store to build subscriptions to its gaming service, xCloud. (Apple has its own competing subscription game service). A Microsoft executive has testified against Apple in the Epic lawsuit, and Apple’s lawyers told the court that “Epic is serving as a stalking horse for Microsoft”. In late June, Microsoft chief Satya Nadella launched Windows 11 with a swipe at Apple’s control over its App Store. “The world needs a more open platform,” he said. “One that allows apps to become platforms in their own right.”

In another theatre of battle, Apple is ratcheting up the privacy features on its devices in ways that mess with the advertising model that underpins the giant of social media, Facebook, and giant of search, Google. In June 2020, Apple said it would begin asking iPhone users whether they want apps like Facebook to track them when they’re using other apps. Facebook said Apple’s move “is about profit, not privacy” by seeking to drag customers away from advertising-reliant free apps from which it earns no commission.

And then on January 28, three weeks after Trump supporters stormed the United States Capitol, Cook gave an incendiary keynote address to a conference in Brussels on computers and privacy.

“An interconnected ecosystem of companies and data brokers, of purveyors of fake news and peddlers of division, of trackers and hucksters looking to make a quick buck is more present in our lives than it has ever been,” the Apple CEO said.

“At a moment of rampant disinformation and conspiracy theories juiced by algorithms, we can no longer turn a blind eye to a theory of tech that says all engagement is good engagement – the longer the better – and all with the goal of collecting as much data as possible.” Relations between Cook and Mark Zuckerberg are reportedly at rock bottom.

Cook at the grand opening of the Apple Tower Theatre in Los Angeles in June.

It is exceedingly strong language for a CEO to use about another business, albeit never named, but clearly identifiable. Why is Cook being so combative now?

“I think what’s happened is that there are many more people today that view privacy as a mainstream issue,” he tells the Financial Review. “Ten years ago, privacy was a niche issue. Today it’s one of the primary issues in people’s minds because people know that the web has become this surveillance tool in all too many cases, and that the building of detailed profiles on people has gone well beyond any kind of reasonable thing.“

Cook sees the upholding of privacy against those “hucksters” and their “juiced-up algorithms” as a human right. And taking a stand has certainly been a trait of his tenure. “We do things because they’re just and right,” he said when asked by investors at a shareholder meeting in 2014 whether Apple should avoid embracing environmental causes. “If you want me to make decisions that have a clear ROI, then you should get out of the stock.“

But even then, there is a business imperative to Cook’s campaign against tracking; it’s become a sales pitch, quite literally. Earlier this year, Apple plastered billboard ads across Australia that featured just three words: Privacy. That’s iPhone. And privacy, coupled with security, has become a shield that Apple uses to deflect allegations of anti-competitive conduct.

The European Commission, and some members of the US Congress, are looking at imposing rules on how Apple manages its own App Store. Does Cook accept that given Apple’s size, outsiders will increasingly want to tell his company how it runs its business?

“Well, I think scrutiny of large companies is fair. And I start from the premise that regulation is necessary in some areas. And so it becomes a matter of determining where it’s necessary and where the focus should be . . . In our model, the user is where the power exists because it’s the user who decides when they buy a phone, are they going to buy an iPhone. Are they going to buy any number of Android phones? And so it’s a fiercely competitive market. And then the market inside the App Store is also fiercely competitive . . . And so there’s huge competition in all areas of this.”

Is competition always a good thing?

“I can’t think of a case where competition is bad,” Cook says. “I think competition is inherently good.“

It’s at this point that anyone who’s squared off against Apple might do a double take. Australia’s major banks, as the Financial Review points out to Cook, have tried to get access to the near-field communication chip on iPhones so they can offer their own “tap and pay” apps, like they do with Android phones. Apple refused, arguing, in part, that this would compromise the security of its iPhone.

Three of the four major banks tried to get the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to allow them to collectively bargain with Apple (a case of big banks feeling very small against big tech). In 2017 the ACCC refused, siding with Apple and cementing its beachhead in the payment system. Last month, Bloomberg reported that Apple plans to offer its buy now pay later service, taking on PayPal and Afterpay.

When asked whether Apple’s growing scale – it commands 56 per cent of the Australian mobile market – makes it harder to argue that security concerns are grounds to block competitors, like Australia’s banks, Cook says it’s “more than an argument” that he’s making. He essentially claims that major banks cannot be trusted to keep the iPhone’s components secure.

“It’s the reality. If you put back doors in a system, anybody can use a back door. And so you have to make sure the system itself is robust and durable; otherwise you can see what happens in the security world. Every day you read about a breach, or you read about a ransomware.”

But the field is shifting. In late July, after our interview with Cook, Commonwealth Bank of Australia CEO Matt Comyn urged Parliament and regulators to pay greater attention to how Apple is pushing into the market for payments. Meanwhile, the ACCC has lately been rather adventurous in tackling the power of Silicon Valley. The regulator’s 2020 digital platforms services inquiry has led the federal government to force Facebook and Google to pay Australian media companies – including the publisher of the Financial Review – for displaying links to news.

Fresh from this win, which attracted global attention, the ACCC in April began targeting Apple and Google over how they run their respective app stores. Is the ACCC on Cook’s radar? “Of course,” he replies. “Anywhere in the world that we’re being inspected is on my radar, at least that we’re aware of, and it’s incumbent on us to tell our story and to say why we do what we do.”

In the case of the controls over the App Store, they are there for security, privacy and safety, he says. “Any kind of regulation should be justified by being great for the user. [Regulation] needs to improve someone’s life. Just like an invention or a technology needs to improve someone’s life.“

Australia is a net importer of tech – we buy in more than we ship. But we’ve begun to export fresh ways to regulate the sector. France and Canada are looking at the ACCC’s inquiry into Facebook and Google; our push for new tax rules for multinationals has found favour through the OECD. Epic Games, as well as suing Apple in California, has launched a similar lawsuit here, the only other country where it’s done so.

When its chief executive, Tim Sweeney, was asked why by the Financial Review’s John Davidson, he replied: “Australia is a good climate to take on this fight.” Does Cook welcome our regulatory innovation? “The technology industry has become such a big piece of the economy, it’s natural that it would be looked at,” he responds.

Which is a tightly worded, diplomatic answer to a topic that the Apple CEO is not up for expanding upon – perhaps understandable given the tightrope he’s walking as lawmakers and regulators in Europe and the US get closer. He’s more expansive when the issue is framed positively, in terms of the opportunities the App Store provides to Australian developers. “Australia is a country that’s incredibly innovative, a country that’s incredibly resilient, a country of great creativity. We’ve seen apps come out of Australia that are mind-blowing,” he says.

He mentions Procreate, an art and design app created by a Hobart company that now employs 52 people, and JigSpace, a Melbourne company which allows users to make presentations through augmented reality. JigSpace was highlighted by Apple at its global presentation for iPhone 12 last October. Among the 600,000 Australians who have registered with Apple to develop apps using its software is Yuma Soerianto, who started to code when he was six and who now has nine apps on the App Store.

The Apple Park campus in Cupertino. Bloomberg

Cook likens the App Store to “an economic miracle” through which more than $600 billion of commerce was pumped last year. As such, Apple’s controls are a small hindrance to developers’ access to an extraordinary opportunity.

“As an individual, you can sit in your basement, no matter where your basement is, and you can write an app. And with the touch of a button, you can distribute your app in 175 countries in the world and become a global seller, a global company. You’re not negotiating with a lot of different retailers around the world. You’re not having to worry about converting currencies. You’re not worrying about local regulations. All of the heavy lifting of going into a country is done.“

You can bet that’s the message Apple is delivering to the ACCC, and the Australian government. And Cook has a message for anyone in Australia who wants our tech industry – the great wealth creator of the 21st century – to flourish.

“In [Silicon] Valley, in particular, we have a very sophisticated mixture of universities, like Stanford and Berkeley, venture capital and a start-up community. And a place with great weather where people want to live,” he says. “All of those together add up to an unbelievable, thriving, entrepreneurial area. And I think Australia has all of those.”

Tim Cook was born in 1960 in Mobile, Alabama. His father was a shipyard worker, his mother worked at a pharmacy. His values were shaped by his parents, certainly, but also by historic events that enveloped his childhood.

“I saw these huge movements when I was growing up, some that I didn’t know how huge they were because I was so young. Like Dr Martin Luther King and John Lewis crossing the bridge at Alabama, marching for voting rights; the riots at Stonewall, where gay and transgender people joined people of all races and really revolted against the way they were treated . . . I feel a sense of responsibility to stand on their shoulders and to try to take it even further.”

He studied industrial engineering, got an internship at IBM and spent 12 years there. He worked briefly at Compaq but was lured to join Apple by Steve Jobs and rose up the ranks to become head of operations. If Jobs was a genius of “creative innovation”, dreaming up revolutionary products and pushing his designers and engineers to make breakthroughs, Cook was the guy sourcing materials, ensuring quality control from factories, and keeping costs down and inventory in check. It was work critical to both Apple’s top and bottom lines, but far from the heady inspiration of Jobs.

“In Silicon Valley we have a very sophisticated mixture of universities, venture capital, a start-up community and great weather … Australia has all of those.” Shaughn and John

On October 5, 2011, at the age of 56, Steve Jobs died. A former Apple executive who worked at head office remembers getting a push notification on his phone, and then watching everyone instinctively pour into the main garden between all the buildings. Twelve days later, on the same site, a memorial for Jobs was held featuring performances by Norah Jones and Coldplay. “All six buildings had giant projections of Steve,” the former executive says. “And I just remember Coldplay playing The Scientist. And everyone was crying.”

For Cook, his first task as CEO of Apple was to get the company through the mourning process. Then he had to get it to move onwards, and upwards. Asked about the advice from Jobs he found most useful, he tells a story that he has told once before: “When he called me over and told me he wanted me to be CEO, he said that he had watched the change between Walt Disney and the next person in line at Disney, and it did not work that well because everybody sat around and asked what Walt would have done.

“When any kind of issue or problem came up, there was a level of paralysis in the company. He told me that he did not want this for Apple and that I should never sit around and think about that. And I think that relieved a level of burden that would have been impossible to escape without that advice.

“And then he modelled different behaviours that I have great respect for, like Steve could change his mind like this,” as he snaps his fingers. “He could be so into doing something in a certain way or building a certain product; but if new information came about, he could change. He wasn’t married to his previous thoughts and his previous beliefs if something new presented itself.

“And so there was never the pride that sets in with some people when they have made a big decision and then, ultimately, it becomes clear that the decision is wrong. He could change, and he did over and over again. I think that is an incredible skill to have.”

That snap of the fingers could be deflating; the former Apple executive recalls spending years on a new product that was killed off at the eleventh hour. “Steve was like an 800-pound gorilla in every conversation and decision. He was feared and admired, greatly. Everything and anything could go up to Steve for review. Even something like marketing copy on the website. You’d never put anything up for final review that wasn’t perfect.

“I would say that some of the magic did die with Steve. Apple transitioned as a company that made awe-inspiring magical products to being one of the most consistent-at-operations companies in the world. Under Steve there was more excitement, more intrigue.”

And maybe there is less buzz about its new products or, rather, new iterations of its products: bigger cameras, slimmer screens. But if there are no longer queues outside Apple stores for a new iPhone, it’s partly because under Cook, Apple has mastered the art of production, of logistics, of economies of scale. No one needs to queue any more – there’s a new model iPhone for everyone who wants it, right away.

And after 10 years as CEO, Cook has quietened the naysayers who thought the company was too reliant on the iPhone. Take a look at Apple’s results, which are a picture of how to make the complex seem simple: you can see pretty much the entire business on just five lines. For fiscal 2020, revenue from the iPhone was $US138 billion; the Mac delivered $US29 billion; the iPad provided $US24 billion and the category that Apple calls “wearables, home and accessories” delivered $US31 billion.

The fifth line item is services, which includes iTunes and iCloud, and it was the second-biggest revenue generator overall, worth $US54 billion. And it’s growing quickly. In 2011, when Cook took over, services generated just $US9 billion. The growth in services and the existence of the wearables division is the legacy of Tim Cook.

The growth in services has not just freed Apple from criticism of being too dependent on the iPhone. It’s seen the stock re-rated upwards. Software companies have much higher margins, and attract a higher price-to-earnings ratio than hardware companies. That is the key reason why its market capitalisation doubled to $US2 trillion in just two years.

How to keep delivering this growth? On an earnings call in January, Cook revealed the milestone of 1 billion iPhones in active use, plus 600 million other Apple devices. The company is rumoured to be working on a car; Cook bats away questions from the Financial Review about it. But with 1 billion-plus users plugging in Apple devices, analysts see a clear path ahead for the company to simply sell them more services.

There’s Apple Music and AppleCare. There’s its streaming service, Apple TV+, as well as Apple Fitness+. There’s Apple Pay, to the chagrin of Australia’s banks and the potential launch of Apple Pay Later, which might explain why Afterpay is joining forces with Square. And there’s the money it’s making from the App Store, depending on the outcome of the Epic lawsuit, of course.

And there’s iCloud – those micropayments, perhaps just $1.49 a month, that Apple users make to keep their photos and phone numbers, and all sorts of things they can’t be bothered thinking about, at their fingertips and safely stored in the cloud, for as long as they keep paying. When people refer to Apple’s “walled garden”, it’s often because they’re making a point about the walls.

But there’s also a very beautiful garden of smartly designed products that just work, intuitively and seamlessly, together. Once you’re in, it’s very hard to leave. Or as Cook says, with that homely Alabama accent: “This is why we get out of bed in the morning. We’ve always felt that technology was meant to enrich people’s lives.“

Cook says his philosophy of leadership is to be a good coach. “People are not looking to be told what to do; they’re looking for inspiration, and they’re looking to be part of something larger than themselves. They’re looking for purpose.” As CEO he tries to connect the dots within the company. And to move obstacles out of the way.

When interviewed by Walter Isaacson for his 2011 biography of Jobs, Cook said he never realised how much a CEO needed to take the heat for other people, until he was himself in that role. “I thought that that was because Steve was bigger than life,” he says when asked to elaborate.

“And so I thought, actually, when I became CEO a lot of that visibility would go away. But the visibility went with the company,” he says, with a chuckle. He’s comfortable with the visibility now. Indeed, he’s turning that visibility to Apple’s advantage.

So why is he turning up the heat on privacy, on security, against those trackers and hucksters? He doesn’t make a connection with the rampant virus that’s upended so many rules, so many norms, so many ways of doing business. But he does reveal, midway through our interview, that taking over from Steve Jobs wasn’t the most difficult moment of his career. The most difficult moment was the year that’s just been.

“A huge challenge is losing total control. And so all of a sudden you know that you’re no longer in control over your destiny, that this pandemic had a strange way of shaking us all and reminding us that we are not the ones deciding.”

Don’t miss the 76-page Platinum 70 Magazine inside the Financial Review on Friday, August 20.