The phrase “Spill the tea,” common in queer vernacular, means simply to “share the gossip.” Perform a quick Google ngram viewer search, and you’ll find that there has been a sharp spike in the prevalence of this phrase since 2019. (While ngrams correlate to books, the correlation between the written word, fictive or not, and vernacular is quite strong.)

The year 2019 is, coincidentally, when the popular video-sharing app TikTok had multiple viral videos launch creators to a near cultlike status almost overnight.

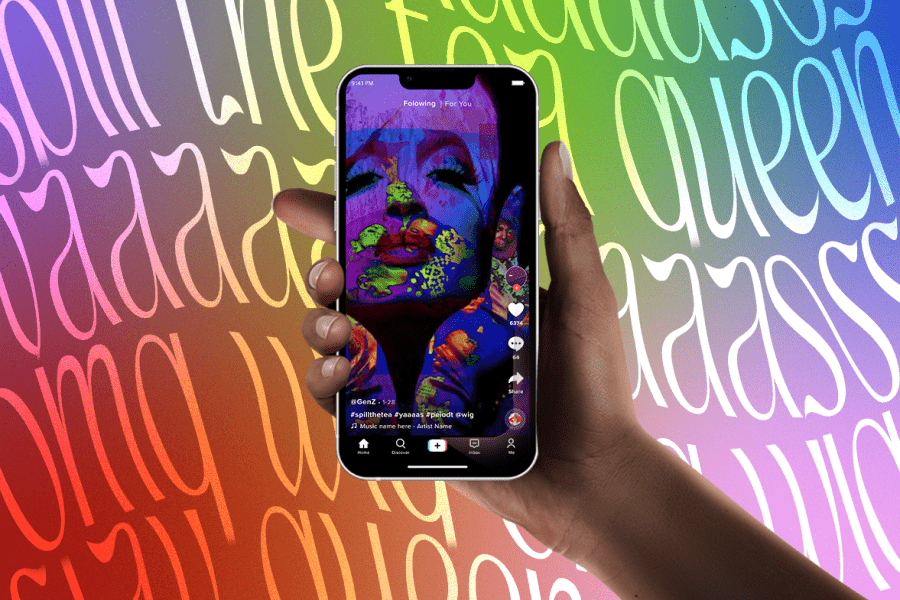

TikTok has a vise grip on younger generations, especially my own. Gen Z is quite invested in the platform, helping the company reach a net worth of $250 billion, the highest net worth of any privately owned companies. The app, an infinite scrolling, short video clip-producing algorithm, learns trends in users and personalizes feeds based on individual likes and dislikes which it learns the more you use it.

Phrases and words become trends and trends become vernacular.

The result of this algorithm is a unique generational culture created by the app, where teenagers like Charli D’Amelio and her sister Dixie became near-overnight millionaires for simply doing the “Renegade,” a popular dance trend; the video landed them television deals, sponsorships galore and tickets to many hallmarks of high society.

Such a cultlike following, however, encourages trends that have a lot of momentum and are hard to be stopped. The language used by content creators and users in comment sections, captions and videos is no exception as phrases and words become trends and trends become vernacular.

The aforementioned virality of one of these videos about “spilling the tea” caused a massive trend on the platform using the audio from the video, inspiring multiple parodies, “duets” and various other spinoffs.

This phenomenon resulted in “spill the tea” becoming frequently used, taking a phrase that had been exclusively used in queer circles and bringing it into the mainstream. I heard “spill the tea” at lunch tables, at local coffee spots and in the comment sections of everyone’s posts. A term used by me and my gay friends had become the newest “it girl” of teenage vocabulary.

The issue lies in the appropriation of NYC ball culture, gay slang at large and African American Vernacular English (AAVE). All of these facets of marginalized cultures, rich in their own right, have been cherry-picked, homogenized, and made stale and palatable to the voracious masses.

While I found it encouraging to some degree that queer language and culture was becoming mainstream, I didn’t find that it coincided with greater acceptance. I remember the same kids who used “spill the tea” recoiling at being asked their pronouns: “I don’t use pronouns; I’m straight.”

Their misuse turns a word born out of the survival of a marginalized group into a joke.

Regardless of the words used, hate often simply stems from prejudice perpetuating itself. The use of queer vernacular to fuel said hate is insulting to the culture I try to venerate and participate in.

These are words stemming from decades of struggle, words that have connected similar people and fostered love in a cacophony of hate. There is deeper meaning to the fun little catchphrases we use — they are not merely the slang of an app or a result of the unprecedented generational unity found in Gen Z. Their misuse turns a word born out of the survival of a marginalized group into a joke.

Instances of “spill the tea” are common on TikTok, and the 2019 incident is a mere microcosm of the platform’s social power. From “periodt” to “wig,” more and more slang from varying cultures has been incorporated into Instagram captions, snappy comment section clapbacks and tweets from corporate acts attempting desperately attempting to relate to an increasingly anti-corporate generation.

The “Blaccent” and other controversies surrounding AAVE are also amplified by this TikTok homogenization. Language like “chile,” “purr” and “finna” have become commonplace in the vernacular of teenagers — the lion’s share of whom are not entitled to use this language in the first place.

This practice also reveals the inherent interdependencies of Black and queer culture and the simple fact that Black people are by and large responsible for a majority of queer culture, especially the balls seen in “Paris is Burning” and FX’s “Pose.” These marginalized cultures are deeply linked, so the homogenization of the language of one intrinsically impacts the other.

While the generational unity that such language fosters is a pro, appropriation of the language is misguided. The widespread nature of such phrases dilutes their meaning and takes a word generated by a marginalized group such as African Americans or those identifying as LGBTQ+ drastically out of context.

I’m all for teaching my straight friends about gay culture and making friendly conversation about what the difference between a “twink” and a “bear” is, but when an Instagram post is captioned “periodt hunty werk queen slay,” it is a flagrant misuse of culture-specific language.

This behavior trivializes the experience of being queer, of being Black and of participating in the cultures where these languages got their start.

I have scrolled through my own infinite feeds, regardless of platform, and seen the latest adventures of my high school graduating class’s self-appointed “hot girls.” Without fail, I see the aforementioned terms littering comment sections of predominantly white girls. “Purr,” “Slayyy,” “It’s giving” … It’s giving what, exactly? It’s giving a regurgitation of phrases that they saw do well on TikTok, and now they have the privilege of being funny for a few months before everyone moves on to something new.

This behavior trivializes the experience of being queer, of being Black and of participating in the cultures where these languages got their start. This slang is older, more impactful and more important than bombarding an Instagram comment section with butchered, stolen words.

There will always be a shifting vernacular, especially in the era of the internet and social media. I recognize that nothing is sacred in a time where everything is connected. However, I am tired of seeing words come out of mouths that have no right saying them. Language is a huge part of any culture, and using and abusing the language of marginalized peoples only diminishes and ridicules the history of their struggle and survival.