Day 69:12This man fled Qatar in fear of persecution because he’s gay. Now he’s pushing back

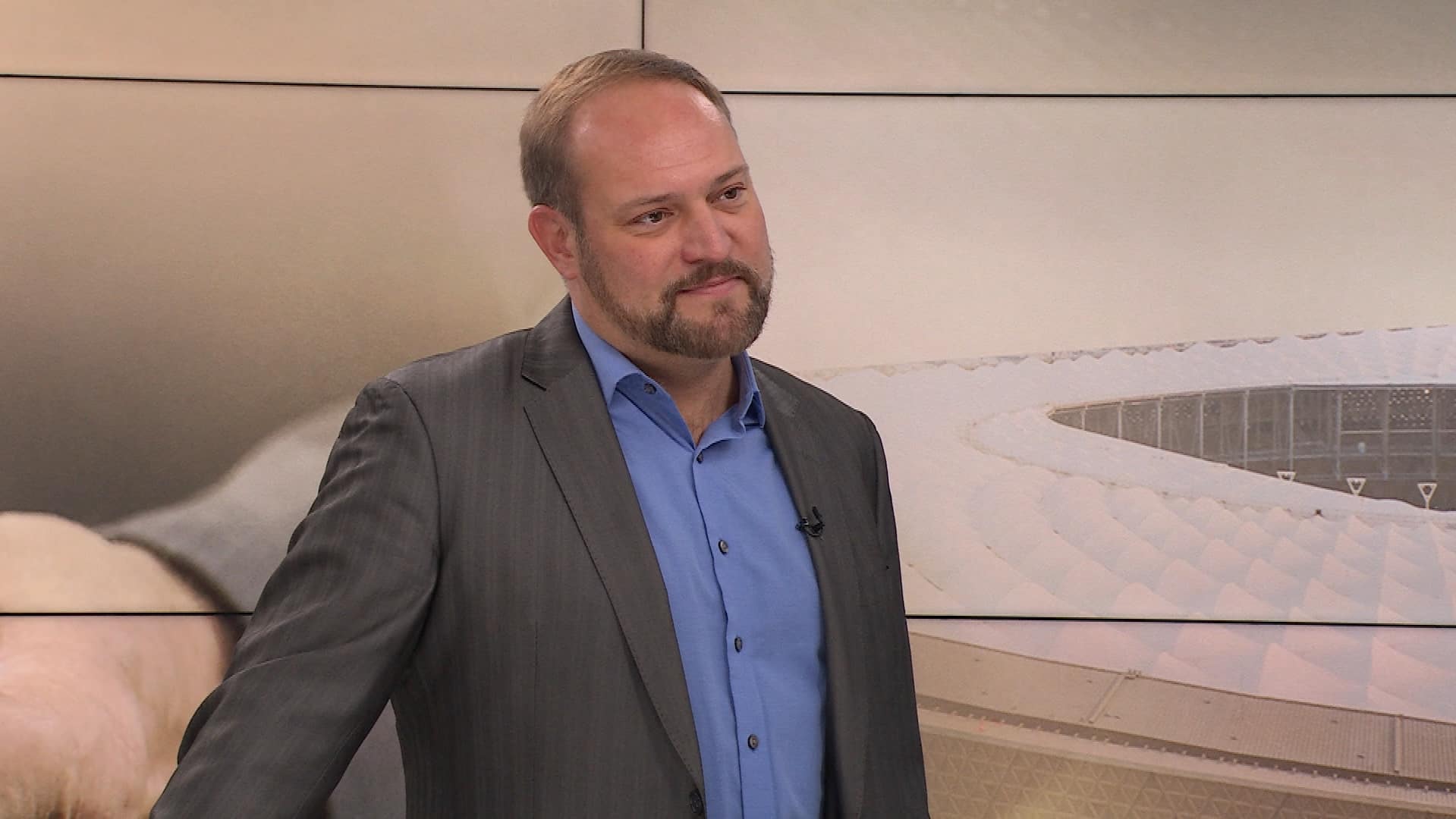

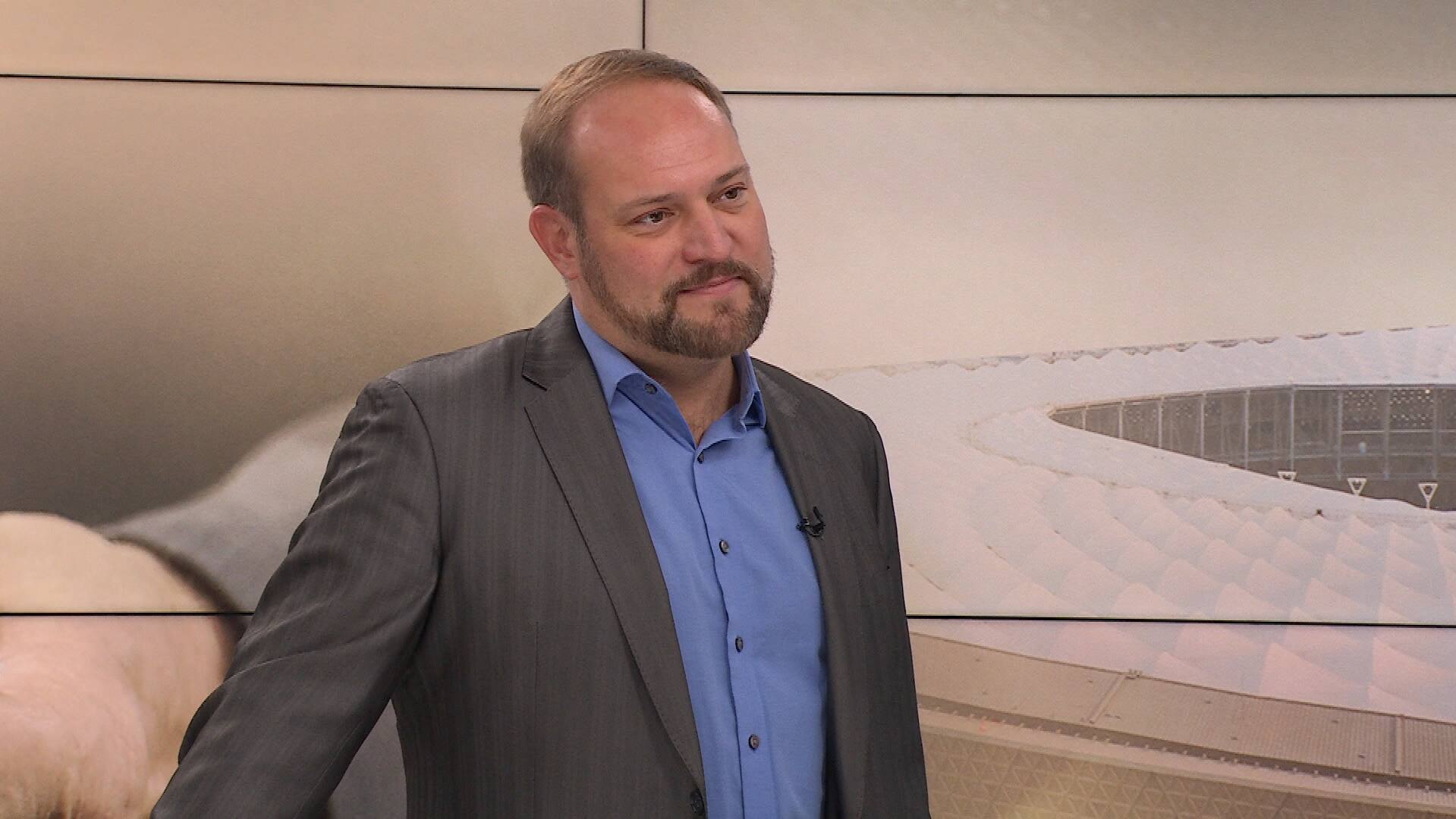

Having been referred to as Qatar’s first person to come out publicly as gay, Dr. Nasser Mohamed thought having the World Cup on his home soil was the perfect opportunity to shed light on the country’s mistreatment of LGBTQ2+ people.

Mohamed has claimed asylum in the U.S. out of fear of persecution in Qatar because of his sexual orientation.

The 35-year-old primary care physician formed the Proud Maroons ahead of the World Cup. It’s an LGBTQ2+ soccer supporters club for Qatar’s national team, named after the colour of the team’s uniforms.

As the tournament rolls on, Qatar continues to face global scrutiny for its criminalization of homosexuality. Despite the Qatari government saying all fans are welcome, visitors are told to respect the country’s culture, with displays of affection being frowned upon.

In May, Mohamed openly declared his queer identity, and has since ramped up his activism, launching the non-profit organization Alwan Foundation. He says its mission is to advance LGBTQ2+ rights in the Middle East with a focus on the Gulf region.

Mohamed spoke with Day 6 host Brent Bambury. Here’s part of that conversation.

What was that like for you growing up there? You now live and work in the U.S. and you’re seeking asylum there. When you were living in Qatar, when was it that you realized you couldn’t live your life in the country where you were born?

Growing up I knew I was different. I knew that I had same-sex attraction. I couldn’t describe how I felt, what was going on with me.

When I was away in Vegas for a conference, I really think that was a moment there. At that point I was still a virgin. I was just trying to talk myself into remaining a good Muslim and not giving in to any temptation and whatnot.

It was just really striking to me that I was not tempted to do anything with women. I remember going to my room and trying to really sit down with that information, because I also had marriage expectations coming up, like after medical school.

[embedded content]

I went to my first gay bar there. It was also an important moment because I had my Qatari passport with me and I was afraid that I would be found out by the government when I showed my identification at the door, which sounds very paranoid.

In reality, there is very intrusive surveillance on us all the time [in Qatar]. We can’t do anything online, even with anonymous accounts, while we live there without getting in trouble. So we feel like we’re being watched all the time.

But then when I walked [into the gay bar] I didn’t even really spend time with anybody. I just knew immediately I was gay. I was like, this is a reality. I just left immediately and went back to my room and had a complete meltdown.

How difficult was it for you to do that, knowing that you might not go back to Qatar for a very long time or maybe not ever?

It was shattering, to say the least. You have all these pieces that come together that give you your sense of self. The way we’re brought up and how we are together as a society really becomes part of you.

Then when you learn that you’re an LGBT person, you immediately know that you can’t be part of that unit as your true self. The following couple of years before I left, I felt like I was dying from the inside out, to be quite honest.

I had to choose living as myself as a way, without any of my culture or my family.

Those are the real life consequences of this severe censorship. It doesn’t make it go away. It just makes us and our families suffer in silence.– Dr. Nasser Mohamed

Are you estranged [from your family]?

Yes. I came out to my family in 2015 and that conversation was just the beginning of the end. Besides the social rejection aspect of it, and the legal aspects of it, there is also a systematic censorship of the issue.

In Qatar, when I was growing up there, you couldn’t see anything about LGBT community on television or in the schools.

When I came out, my parents didn’t even know what that meant. I actually struggled to find terminology to describe it to them in Arabic because I just was telling them I’m different.

It was tough to explain it to them. Those are the real life consequences of this severe censorship. It doesn’t make it go away. It just makes us and our families suffer in silence and alone when we’re faced with it.

Club de Soccer LGBT+ co-ordinator Raoul Gebert denounces FIFA’s attempt at avoiding discussions around human rights.

Now you’re being critical of the country and you’re openly advocating for the rights of people that are being suppressed.

I’m out advocating for our rights, for our rights to be safe. Without persecution.

When you are critical of the country for any reason in Qatar, you’re just considered a terrorist. Basically, I’m considered a criminal in their eyes.

I thought my family, at least some of them, would be extremely angry with me for coming out publicly, which I’m sure they are. But I think their fear of contacting me is stronger than whatever other emotion they might be having. Nobody has said a word to me since coming out publicly.

Now you’re in this position that LGBTQ2+ people from Qatar are reaching out to you. What are they telling you about their experiences?

There is state sponsored persecution of the LGBT community. There is the hunt, jailing, physical torture, mental torture, and ill treatment and detention of LGBTQ targets.

There’s a conversion therapy centre in Qatar that gets referrals from everywhere. Gets referrals from the mandatory military service. Referrals from families that want to make sure their kids are straight again. It gets referrals from law enforcement. There’s like state orders sometimes mandating people to go to these programs.

Until the final game on December 18th, the World Cup will be on and the world will continue to be watching Qatar. Once that last whistle is blown, do you expect the authorities to double down on their crackdown of LGBTQ people, or do you think that the spotlight on Qatar could spark change in the country?

Putting Qatar in the spotlight is not something that makes them change their policies on anything. You can literally put evidence right in front of them and say, “you have done this and this is the evidence,” and they would deny it. This is just the truth. This is what they do.

Now, there are whispers from the local community about what they call “Western cleansing” after the World Cup – which means doubling down and putting things in order. I don’t know how that’s going to look, but I’m hoping that there will be a platform and a channel to continue to shed light on whatever happens there. So, that’s what I’m hoping to do.

With files from Devin Heroux. Radio interview produced by Pedro Sanchez.