Instead of focusing on the killer, Green opts to humanize his victims. This proves a thorny task when dealing with men who led pointedly secret lives. In the book’s epilogue, he explains that he was motivated by the lives that these men “wanted but couldn’t have. Here was a generation of men, more or less, for whom it was difficult to be visibly gay. To be visibly whole.” I would have put the emphasis on visibly rather than on whole. Closeted gay people do, of course, lead rich, satisfying existences, even if they leave fewer traces. One of the perils of writing about marginalized murder victims is that their lives can be framed as one long sorrowful arc of victimization — in a sense fated to be found dead in a trash bag on the side of the road. Gay men pressured to hide their sexuality at the height of the AIDS epidemic are particularly susceptible to all-consuming tragic narratives.

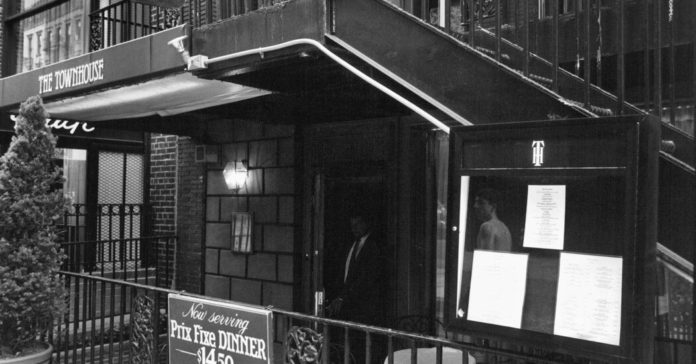

Green seems to anticipate this journalistic conundrum. With great compassion, he widens his scope to explore the social value of gay bars to the queer community and the vital work of grass-roots groups like the New York City Anti-Violence Project, which fought for fair treatment for gay crime victims during a period when they were often treated like career criminals. He also fills the narrative void by telling the stories of bar patrons and employees, including those of the cultishly popular piano players who serenaded the victims and their murderer. As a result, Green proves a conscientious crime writer. He provides an adrenalized police-procedural plot without ever losing sight of the fact that these were innocent human beings who were duped, butchered and discarded. We are never allowed a moment of perverse awe for the murderer.

Ultimately, that strength is also the book’s weakness. In 2000, thanks to advances in forensic science, the trash bags were reanalyzed for fingerprints, which led back to Richard Rogers Jr., a nurse at Mount Sinai Hospital who lived on Staten Island. In the chapter devoted to his life, he is described in all the ways a person never wants to be remembered unless he is an opportunistic murderer: normal, average, gangly, introverted, unassertive, round-shouldered and sunken-chested, someone who walked without swinging his arms. Rogers was tried but not convicted of murdering a male roommate in 1973, and it is likely that his killing rampage exceeded the number of victims found by chance on roadsides in the early ’90s.

Green acknowledges that Rogers, who is serving two consecutive life terms in prison, declined his attempts to interview him. That missing confrontation creates a fissure in his otherwise impressive reporting. Exactly how, where and why Rogers killed remains a vexing mystery. More than once in the abrupt final chapters, in the midst of reading about him, I forgot the murderer’s name. But it is to Green’s credit that I never forgot the names of the four known victims. How many serial-killer victims can you name?