Monsters in horror films aren’t just scary, or dangerous. They also “make one’s skin creep,” the philosopher Noël Carroll wrote: “Characters regard them not only with fear but with loathing, with a combination of terror and disgust.” It’s no coincidence, then, that horror is strewn with characters who are openly, or coded as, queer and transgender—and that they’re almost always the dirty, lecherous, bloodthirsty villains, seldom the victims. Think of films such as The Silence of the Lambs and Psycho, with their suggestion that the gender confusion of their “cross-dressing” villain is the impetus for their violent desires.

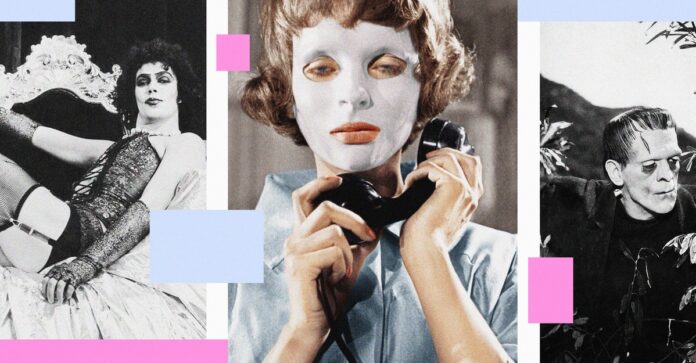

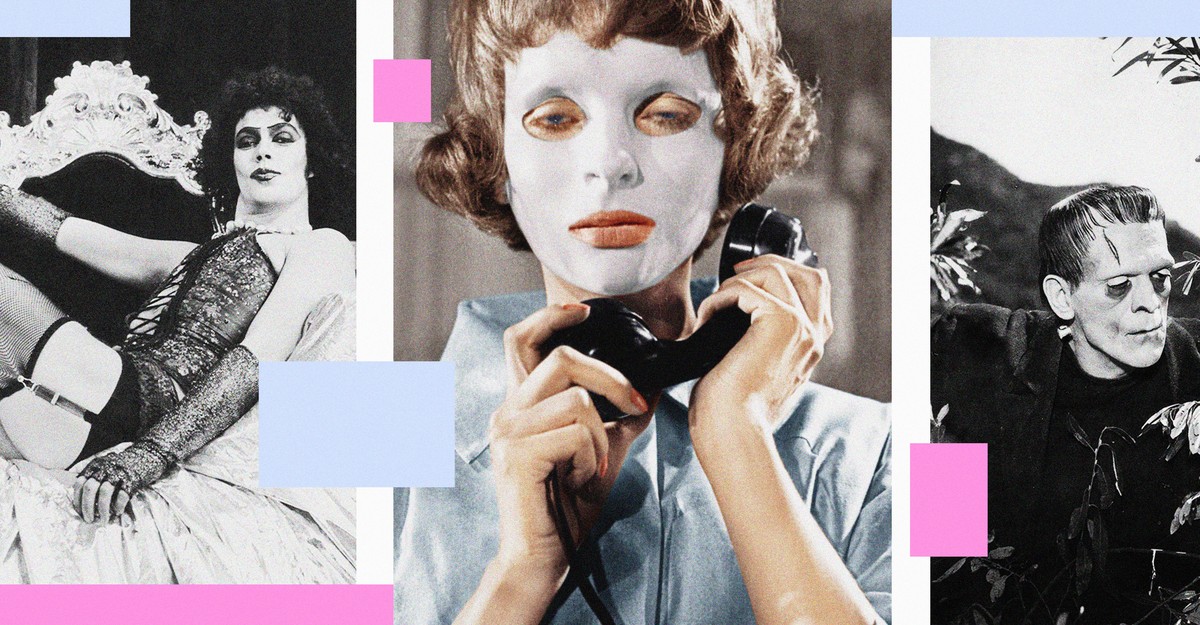

Despite such one-dimensional portrayals, queer and trans people have long found camaraderie in horror. Take Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein, which has inspired countless explicitly queer retellings, including Jeanette Winterson’s 2019 Frankissstein and the 1975 camp classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show. (The latter, if you need a refresher, follows a young couple’s desperate bid to escape the home of the infamous “Sweet Transvestite” Frank-N-Furter, who, among other things, has created a muscle man named Rocky in his laboratory to be his companion.) In a 1994 essay, the transgender writer and theorist Susan Stryker described identifying with the bloody origin story of Frankenstein’s monster: “The transsexual body is an unnatural body. It is the product of medical science. It is a technological construction. It is flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born.”

If monsters typically function as a mirror for society’s deepest anxieties, writers such as Stryker go a step further. By intentionally mapping themselves onto well-known monster roles, they force a closer reading of what these works actually demonize—whether that’s free gender expression, pleasurable sex beyond the nuclear family, or other ways of living outside of societal norms. The new anthology It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror mines this vein; its contributors suggest, in various ways, that the monster’s perspective isn’t just legitimate, but maybe even morally superior.

Queer writers often mark the tendency of horror-movie villains to wear masks, by force or by choice, as a way of concealing who they are from a terrified and unaccepting public. The writer Sachiko Ragosta speaks to this enduring image in the essay “On Beauty and Necrosis,” about the 1960 horror film Eyes Without a Face, which centers on a young woman whose father attempts to cover up her scarred face with a beautiful synthetic mask. In the character’s plight, Ragosta recognized their own childhood cover-ups—for instance, wearing dresses and bras in grade school to look more like a “girl”—and their struggle to accept that they were nonbinary. “Coming into my queerness,” Ragosta writes, “was an agreement to no longer borrow someone else’s skin to hide myself.”

Even horror narratives with more difficult or unsavory story lines can help people see themselves. For Viet Dinh, 1983’s Sleepaway Camp, in which teenage campers are mysteriously murdered one by one, is one such film. Angela, a bullied and miserable girl, is positioned as the victim until the final scene, in which she’s revealed to be the killer—and shown to have a penis, right before the screen turns black. The double reveal draws a harmful and frustrating connection between transness and violence, and Dinh observes that “being trans has been forced onto [Angela], as opposed to something she adopts for herself.” But he’s also fascinated by her: As a kid, he too had gone to camp and struggled to conform to the gendered social behavior that others expected. He writes that, watching the film, “I found myself: a swirl of gender confusion; the first stirrings of desire; the nexus of rage and confusion; and, perhaps, the hope of love.”

The kinship that some viewers feel with such films complicates the question of what good or harmful representation of queer or trans identity looks like, as Carmen Maria Machado explores in an essay about the 2009 cult horror film Jennifer’s Body. The movie follows Jennifer, a demonically possessed cheerleader (played by Megan Fox) who kills off her male classmates while her best friend, Needy (Amanda Seyfried), desperately tries to stop her. A pivotal scene has since become an internet meme: As Jennifer prepares to kill Needy, the latter says, “I thought you only murdered boys,” to which Jennifer replies, “I go both ways.” Although many now view Jennifer’s Body as a feminist film, some critics denounced the film upon its release, noting its fetishization of young female desire.

Machado, however, argues that the film is a rare and honest portrayal of bisexuality. She points to the many different types of intimacy the protagonists share: The girls exchange longing looks at school that a classmate categorizes as “lesbigay”; at one point, they even kiss on Needy’s bed. Jennifer’s Body succeeds because it portrays curiosity and experimentation between two girls without the pressure of a perfect label or a happy, romantic ending. “How little we know of ourselves at any moment; how distinctly human that is,” Machado writes. “There is such little grace given to the perfect messiness of desire.” As a villain, Jennifer is allowed to experience this desire in a more human way than if she were a regular girl.

To identify with a villain is to recognize that fear is a reflection—of who or what we believe capable of inevitable harm. We see this reflection turned on its head again and again throughout It Came From the Closet, including in S. Trimble’s essay about the demon in The Exorcist and in Bruce Owens Grimm’s queer reading of Hereditary. But embracing monstrosity also transcends horror. I’m reminded of the gay singer-songwriter Perfume Genius, who, in his 2014 smash hit “Queen,” boldly sings, “No family is safe / When I sashay.” Rather than mold his sexuality to fit a straight public’s expectations, he insists on a fully realized existence. Whether in the horror genre or outside of it, queer people will continue to identify with villains until their own identity no longer inspires fear.