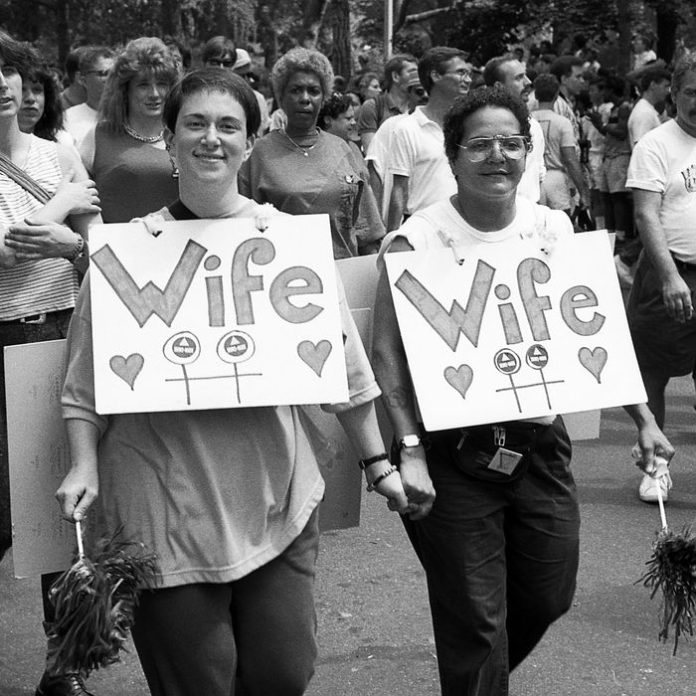

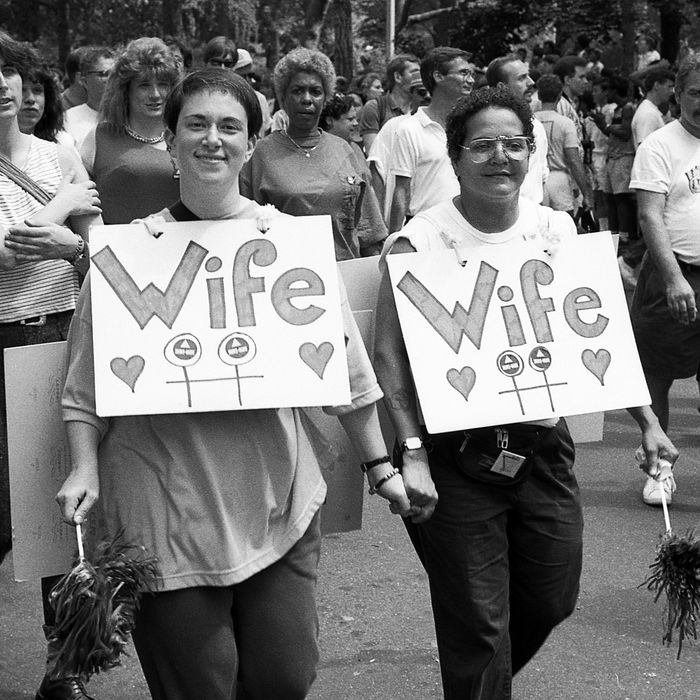

In a single generation, same-sex marriage went from being almost unthinkable to being the law of the land in all 50 states — a pace almost unprecedented in American history for a civil rights movement. In his new book, The Engagement, author Sasha Issenberg traces the twisting path that marriage equality took to become an almost unquestioned aspect of American life. Issenberg, a critically acclaimed political journalist who has covered presidential elections for publications like The Boston Globe and Bloomberg News — as well as the author of the book The Victory Lab, which is about the science behind political campaigns — spent nearly a decade chronicling the battle for same-sex marriage. He spoke to Intelligencer about what he learned while researching the book and the lessons the marriage-equality fight holds for other political movements, such as the fight for transgender rights.

An idea that was sort of fringe 30 years ago is now acceptable, and an almost unquestioned part of the fabric of American life. How did this happen?

We stumbled into this as a country. I think there is this natural impulse as we look back from the outcome, a Supreme Court decision that guaranteed marriage equality nationwide, to assume it was inevitable. It certainly wasn’t inevitable that it was going to end with this becoming the law of the land, not as quickly as it did. But it was not even inevitable that we were going to fight over this! It was not inevitable that this was going to be a goal of the gay rights movement.

The story I tell starts in 1990. And at that point, there’s not a single national gay rights organization that has endorsed marriage rights as an objective. None of the religious conservatives who spent their days fighting gay rights were trying to stop gay people from getting married. There was hardly a politician in the United States who had ever been asked his or her opinion on the subject. And where the book starts is with a PR stunt in Honolulu where a local activist brings three couples in to request marriage licenses from the Health Department. And he’s not a lawyer. He doesn’t have a legal strategy. But due to a sort of freakish set of events, the Hawaii Supreme Court rules in his favor. Part of this history that becomes familiar to people starts with the Defense of Marriage Act, then a state-by-state battle through Vermont and Massachusetts, is effectively the rest of the country responding to this thing that came out of nowhere in Hawaii.

Reading the book, you get the feeling that there was this set of coincidences that happened. How unique is this? You think of the civil-rights movement, or women’s rights, where they had a strategy and a plan for what they’re going to accomplish.

The conventional story that is told about school desegregation starts 40 years before Brown v. Board of Education, with lawyers at Howard University law school plotting the sequence of incremental cases that will allow them to eventually try to desegregate public schools. Suffrage, there was a 50-year organized movement. What is remarkable is that there was not a national strategy to win marriage equality until gay marriage was already the most divisive issue in the country. I wrote about how, in 2005, a group of lawyers and representatives of the big gay-rights organizations met in Jersey City to set a national strategy. And they laid out a plan where they thought that they could win marriage nationwide by 2025. But at that point, they were already catching up to the emergence of this as an issue. In 2005, gay couples were already marrying in Massachusetts. The president of the United States had already campaigned for re-election supporting a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage. Nearly 20 states had already banned it in their constitutions. So the strategy followed, rather than catalyzed this movement.

And as the strategy unfolded, it felt like a lot of cultural shifts followed, too. You write even when same-sex marriage was deeply politically unpopular, there was still not a desire for people to identified opposing publicly.

I think that there’s really an elite opinion story here that’s different than the popular opinion story. There were three trials over gay marriage: In Hawaii, in 1996, in federal court in San Francisco in 2010, and then, a few years later, in federal court in Detroit. And every time, the problem got worse and worse for opponents of same-sex marriage. In each case, a state had to present a rationale for excluding gay and lesbian couples from marriage. And they could not find credible, expert witnesses. They wanted to argue that, basically, the children raised in same-sex households were worse off than those in opposite sex households. And there actually was not social science research that demonstrated that. But also, I think there was a cultural shift. Even in 1996, gay marriage may have been polling at 27 percent nationally, but finding a tenured academic anywhere in the United States who wanted to be seen as the face of that opposition in a high profile trial was impossible. And that’s obviously all happening as people were coming out of the closet in greater numbers, and creating a sort of street level atmosphere of familiarity with not just gays and lesbians, but the types of relationships that they have.

I keep on thinking back to the Steve Bannon line about politics being “downstream of culture,” and how much elite opinion really ended up shaping popular opinion. Were elites in 2000 where popular opinion was in 2010?

Yeah, with the exception of one category of elites, which is politicians. Elected officials and candidates were almost always followers of public opinion, not leaders of it. A lot of the story I tell through Barack Obama, because his entire career took place in the 25-year period that I write about. The arc of his career is incredibly revealing, because he always manages to find what seems to be the safest position for the constituency that he’s looking to represent.

In 1996, he’s running for the Illinois state senate from a liberal Hyde Park district in Chicago, and he says that he supports gay marriage. He later disowns that, and basically blames a staffer for having mis-answered a questionnaire. But four years later, he’s running against Bobby Rush in an overwhelmingly African American South Side district for Congress, a district in which Black churches play a big role. And now he’s not a supporter of same-sex marriage any more. And as civil unions emerged that year, in 2000, as this kind of compromise, Obama becomes a civil-union supporter. He runs for Senate in Illinois (which outside of the Chicago area is a socially conservative place) as a same-sex marriage opponent who supports civil unions. And what you see is that Obama only comes out as a supporter of same-sex marriage until the issue has broken 50 percent in national polls. And I think that’s pretty illustrious.

Hollywood executives and creative types, the people who edit the New York Times wedding sections, which started including gay couples before this was a nationally popular issue, social scientists who were being asked to testify — they were probably ahead of public opinion. But politicians were almost always behind it.

Same-sex marriage is legal in all 50 states, and it seems relatively unquestioned on the right. Is the war over?

One thing that’s apparent is that there is not any effort to approach Obergefell v. Hodges the way that the right has approached Roe v. Wade. I don’t know anybody who thinks that the core holding of Obergefell, which is that the fundamental right to marriage extends to same-sex couples, is likely to be reversed by the Supreme Court at any point.

What has happened since that ruling in 2015 is that the political and legal energies of the religious conservatives who had been fighting and lost the marriage fight have sort of gone in two separate directions. One is toward religious-liberty exemptions, often on issues related to marriage. There’s now a case before the Court about whether a Catholic social-service agency has to place foster children with same-sex parents. There’s a good chance, in this case, that this right-leaning Court in particular will get very deferent to people who claim that having to accommodate gay marriage in their private actions offends their religious values. If the Court rules in favor of these religious exemptions, the right’s demands are only going to get bigger in future cases. And I could easily imagine a scenario where an employer can decide that they will give dental insurance to the opposite-sex spouses of their employees, but not to the same-sex spouses of their employees. We could end up in a position where the right is arguing really directly that, “Yes, gay couples are allowed to legally marry in states. But nobody has to actually treat those marriages as interchangeable with heterosexual ones.”

That’s one big push. And then the other thing is, obviously, all the transgender issues. One thing that happened even before the Obergefell decision, that religious conservatives acknowledging that they had lost the fight over gay marriage decided to go where public opinion was friendlier. And that was towards all sorts of issues relating to transgender rights and identity.

Is it fair to view some of that as rear-guard actions by religious conservatives? They’ve lost the broader war, but they’re trying to at least pick a couple of pockets on friendlier terrain. This is them fighting from the bunker.

Yes. You know? I think that this is the one position where they can still claim that they’re majorities. On most basic gay rights issues, they cannot marshal majorities. The whole movement that once called itself the quote-unquote “moral majority” is now, often, describing themselves as a besieged minority. I mean, watch Fox News for five minutes at any point of the day, and the message is no longer, “This is a Judeo-Christian country. The law should reflect our conservative values.” It is, “Religious conservatives are a minority besieged by powerful political, academic, media, business interests who need special protection from the courts because they can’t get their way through the political process.” And in some ways, the trans fights are a throwback to where the right was on gay marriage and other gay issues in the 1990s and the 2000s, when they could look at polling and say, “Hey, there’s a majority here for our view.” One thing: I doubt it’s likely to last, and for a variety of reasons. One thing we saw with gay marriage that we also see on trans issues, is that young people are always more liberal than older people across race, ethnicity, and gender. And so the generational change is going to push us only in one direction. The other big variable is that the science is still in flux. And one thing that dramatically changed the foundation on which the political fight over gay marriage was waged was that we have a very different understanding of how and why people end up gay now than we did in the ’90s. Everybody basically accepts that heredity plays some major role in this, and it becomes a lot harder to justify discriminatory policies when you’re not talking about it as a lifestyle choice. And I suspect that in five, ten, 20 years, our understanding of the biological underpinnings of gender identity are going to be dramatically different than they are now. And much in the same way that our understandings of sexual orientation are dramatically different than they were 30 years ago.

One similarity between the fight over trans rights that’s similar to the fight over marriage is that a lot of this was pushed by business interests that are not part of the traditional progressive coalition. How important is that?

I think the really important thing is that at the state level this became seen as a basic competitiveness issue. Some of the fights that have taken place after Obergefell over LGBT rights were Walmart pushing back in Arkansas and Eli Lilly pushing back in Indiana. It’s probably hard enough to get engineers, analysts, and coders to move from San Francisco to Bentonville to work for Walmart without having to deal with the issue that they’re going to potentially lose all of the material benefits that come along with being a legally married couple, and that they would have basic civil-rights protections where they live. A lot of the states that have been laggards on LGBT-rights issues — we’re talking largely southern and rural states here — are deeply involved with a few large employers who have a lot of leverage in the legislature, and in terms of public opinion. One of the shifts that took place in the marriage debate was the emergence of a handful of major donors that raised gay marriage to the top of the gay-rights agenda, but also a few well-targeted boycotts and shaming campaigns that made folks on the other side of the issue really reticent to be associated with it. We’re now seeing that LGBT rights are kind of a core plank of the corporate agenda in the United States.

It seems very hard to replicate a path in which an issue that is a view that’s not widely held becomes a base part of the corporate agenda in a generation. Can that be replicated?

There are definitely folks across social movements today who are hoping that there is some sort of off-the-shelf playbook from gay marriage that they can apply to their issues. And I don’t think it’ll be that easy for any of them. There are things about the marriage fight that are distinctive and don’t translate to other issues. But I think there are a bunch of discrete lessons from the history of this that are useful.

One thing is understanding the intersection of political and legal activity. The early victories were won through the courts, and in the case of Hawaii and Vermont were lost through the political process [in Hawaii, a court decision on marriage was over turned via referendum, and in Vermont, the legislature passed civil-unions legislation] , because there hadn’t been the political organizing and lobbying ahead of time to keep politicians out of a constitutional process. For gay marriage activists, they have to fight really hard at the legislature to basically just keep politicians from amending the state’s constitution to ban something after the top court has ruled. So I think that there are areas where — because of the structure of interest groups — the people who do lawsuits and the people who do campaigns are fairly far apart from one another. And I think this is just a really instructive lesson that strategies need to take both those things into consideration and anticipate.

A big thing that happened was the development of a single-issue group called Freedom to Marry whose only objective was marriage equality. One of the critiques of existing LGBT groups — most notably the Human Rights Campaign — was that they hadn’t fought hard enough for marriage. I don’t think it was that they necessarily were wimping out. I think the issue was that they had defined a very broad coalition whose interests they served, and that forces them to be concerned about long-term relationship building. Why does it make sense to pick a fight with a moderate Democrat who votes the wrong way on the Defense of Marriage Act if that means it’s going to be harder for you to get into their office the next time you’re asking for AIDS funding? What was novel about Freedom to Marry was that it said, “We have this one goal, and we’re going to put ourselves out of business as soon as we get it.” And they did that after, in 2015. Most interest groups end up serving the goal of their own existence. They care about satisfying donors, members, and their long-term relationships. And they make a lot of probably reasonable decisions about priorities and trade-offs with those values in mind. Freedom to Marry didn’t have to do that. And so they could invest deeply in research just focused on how you win people over to marriage and then they also could support more adversarial politics against opponents of same-sex marriage because they weren’t necessarily worried about blowback onto other related issues.

Another thing there that struck me is that there was no real focus at all on federal legislation.

I think it became clear to them at some point that they were going to have a better chance of overturning the Defense of Marriage Act at the Supreme Court than they would through Congress. But otherwise, this was a state-by-state fight. And that meant that in just about every state in the country, they had to be in the position to be on offense and defense simultaneously. Freedom to Marry, it’s very conscious of the broader cultural environment in which justices would rule on this. So they focused on getting public opinion over 50 percent so that when Anthony Kennedy opened up his newspaper and saw polling on gay marriage, he would be aware that if he decided to strike down state bans on same-sex marriage, he would not be getting out ahead of what the American people wanted. And then they ended up spending a significant amount of resources during those years trying to move public opinion. They were not going to actually have an effect on state laws by moving opinion in those places, but they could help build an environment in which justices felt that they weren’t going to be seen as going farther than the public could stomach.

That it wasn’t going to be a Roe v. Wade situation where there was concern that the justices had jumped in advance of public opinion.

Exactly. I think that the backlash to Roe v. Wade hung over a lot of the calculations made by folks as they looked at when and how you go before the Supreme Court, and the potential dangers of going there prematurely. Even if you think justices will be responsive to your legal arguments. That either they might be ambivalent about the backlash, or that you might not be able to defend. You might create new opposition just by dint of how they handled it.

Is there any political movement right now that has the potential to be this successful over the next 20 years? 30 years?

Cannabis legalization feels pretty similar to me. I think 20 years ago, there wasn’t a politician in the United States that was in favor of legalizing any drugs. NORML was seen as a kooky outlier organization. I do not think this was treated by the media and the political class as a serious political objective. And what we’ve seen is a significant shift in state laws. We’ve seen, obviously, a massive jump in public opinion on this. And, not unlike marriage, while states have a lot of leeway to set their own policies around substance availability, ultimately, you need a coherent national framework for things to happen. We’re starting to see with the efforts to reform federal banking laws that a sort of similar effort to standardize the federal architecture around drug laws so that states can pursue their own policies on this. It’s now totally normal for major national politicians to say they support cannabis legalization. And we’re starting to see serious, ambitious politicians say they support legalization of harder drugs. We may end up in a situation where, similarly, business communities that were not first movers on this thing see it as a sort of economic development issue if their states are being left out.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.