Maigen Sullivan wants folks to know the South isn’t always 20 years behind.

Sullivan co-founded the Invisible Histories Project, which works to collect, archive and preserve the history of LGBTQ southerners, after becoming frustrated with the lack of historical context available while working with queer communities at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

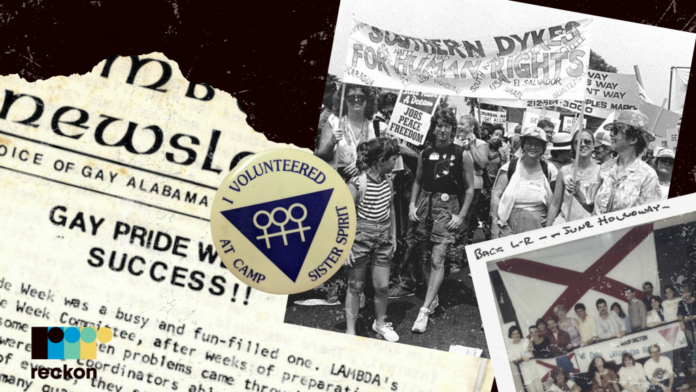

Sullivan said queer folks in the Deep South have been documented organizing and taking care of their communities—even finding success politically— since at least the early 70s, a fact that doesn’t fit neatly into the “lacking South” narrative often highlighted in popular media.

IHP was awarded a $600,000 grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to continue their work preserving LGBTQ history and adding community programs in Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia,

Reckon caught up with Sullivan to talk about why it’s important to gather and highlight queer southern history. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Reckon: How did the Invisible Histories Project start?

Maigen Sullivan: Josh Burford, my co-founder, and I met at the University of Alabama at Birmingham while I was working there doing LGBTQ services and he was working at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, doing a similar position and archiving work in the city. He came down and did a presentation at a conference that we were hosting, and we got to talking about the work that he was doing in Charlotte, and the frustrations we felt in our positions that so much of the work we were doing was very ahistorical. It really wasn’t rooted in the history and the legacies of the folks who had come before and we felt that was missing. So we were like, ‘could we do this work that we’re doing, on a bigger, statewide scale?’ And so we started planning and plotting.

You said your work with queer folks on campus felt ahistorical. Why is it important to have your work rooted in history?

I think it’s important to honor and respect and validate the work of people before us. I think we’ve done a very poor job—we’re getting better at it— of honoring elders and of talking about the legacy of the work that people before us have done. But also ,to give current young people engaging in the work or just trying to figure out who they are, a foundation. Like this has been done. No, you’re not the first. You are one person in a long legacy community who’ve come together to advocate for change—and have been successful. All we hear about the South is how awful it is to be queer and trans here. We hear the statistics; we hear the sad stories; and those are important. But when all we do is talk about the lack, the hurt and the deficit, we internalize suffering. And we have to have moments of joy and moments of triumph in order to keep going and in order to not think that’s all we can be. I think history really does that. It really gives us something tangible to hold on to.

What’s something that you learned about queer history in the South, that has stuck with you or inspired you?

One of the things that I’ve currently become a little obsessed with is Lambda Inc. Lambda Inc. started in 1977. Four friends, two gay man and two lesbians in Birmingham Got together at Bootsy’s Bohemian Cafe and they start talking about how their issues [regarding the LGBTQ community] weren’t really being addressed in any kind of way and there was no concerted effort to provide both space for them to connect with others or advocate for themselves politically. They started Lamda Inc., which was the first LGBTQ Center in Alabama. It led to a lot of the things that we still see like the Birmingham AIDs Outreach. I had never heard of them— going to multiple community events and hearing about people’s stories working at UAB, and never once heard them mentioned… This is living history and I had no idea, and nobody else seemed to, which says to me that we’ve done a poor job letting these folks know that this is invaluable history and it needs to be preserved.

Are there things people can do to participate in collecting the living queer history of the South as well as the preservation of personal archives?]

We are actively accepting collections. Email us at contact@invisiblehistories.org. Twitter, Instagram and Facebook are a really great way to see the kinds of things we’re accepting.