There’s a secret in the Mount Cemetery of Guildford, an English town about 32 miles southwest of London.

There, buried in one of the graves, are two gay lovers: Edward Carpenter, a man called the “gay godfather of the British left” and his longtime partner George Merrill.

Though some may not recognize them by name, both men bucked the homophobia of the late 18th and early 19th centuries by living together in an out gay relationship, providing romantic inspiration for two books written by well-known gay authors in the process.

Their final resting place has recently been designated as an LGBTQ historic site by Historic England, an organization that helps people care for, enjoy and celebrate England’s spectacular historic environment.

Who was Edward Carpenter?

Born in 1844, Carpenter knew he was gay from an early age. In his diary, cited by Surrey Live, he wrote, “At the age of eight or nine, and long before distinct sexual feelings declared themselves, I felt a friendly attraction toward my own sex, and this developed after the age of puberty into a passionate sense of love.”

He studied at the prestigious Trinity Hall college at the University of Cambridge. There, he developed romantic feelings toward his friend Edward Anthony Beck, who also served as Trinity Hall’s master. When Beck eventually ended their friendship, Carpenter was heartbroken.

Carpenter said the work of gay American poet Walt Whitman caused “a profound change” in him, as Whitman urged people to find divinity in nature and within themselves rather than in religious society. Though Carpenter served in the Anglican ministry until age 30, he gradually grew dissatisfied with church and university life. He left both to begin publicly lecturing on astronomy, historic Greek women, and music.

When he moved to the town of Sheffield at age 31, he encountered many manual workers. Historians note that his poetry around this time expressed attraction to these workers, to “the grimy and oil-besmeared figure of a stoker” and “the thick-thighed hot coarse-fleshed young bricklayer with a strap around his waist.”

Carpenter’s romance with a working-class laborer

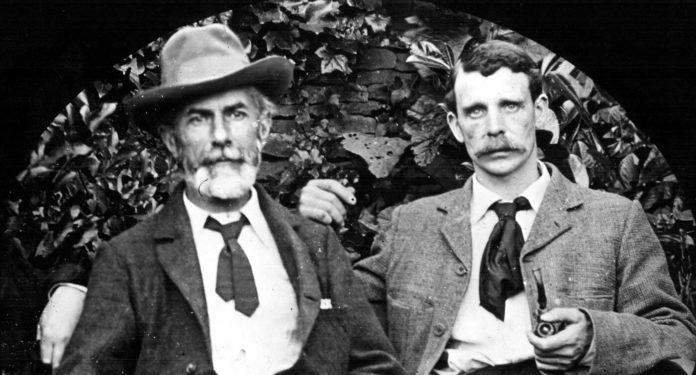

As such, it’s hardly surprising that at age 47, he met and fell in love with Merrill, a working-class man who (unlike Carpenter) grew up in the slums and had no formal education. The couple met on a train after Carpenter returned from travels in India. Merrill worked numerous blue-collar jobs at a newspaper office, a hotel, and an ironworks. Seven years after meeting, the two men moved in together into Carpenter’s small farm home in Millthorpe, Derbyshire.

There, Merrill officially served as Carpenter’s servant, cooking, cleaning, and decorating their home in fresh flowers. Carpenter liked Merrill’s baritone voice and enjoyment in singing comical songs. Carpenter once wrote of him, “George in fact was accepted and one may say beloved by both my manual worker friends and my more aristocratic friends.”

Their living openly as a gay couple was especially notable considering that, at the time, the United Kingdom had laws punishing “buggery” with prison time. Famed Irish playwright Oscar Wilde was placed on trial for homosexuality in 1895 and shunned by society — countless other men had their lives ruined under similar offenses.

But despite this, Carpenter openly defended same-sex relationships in his 1895 book Homogenic Love, his 1896 work Love’s Coming of Age, and 1908 creation The Intermediate Sex, calling same-sex couples “not only natural but “inevitable,” Surrey Live reported.

The books generated controversy, even leading one of Carpenter’s neighbors to report him to the Derbyshire Police. The police pledged to keep a “discreet watch” on him and his activities.

Carpenter and Merrill’s impact on history

Carpenter became friends with Whitman and other influential writers like Indian writer Rabindranath Tagore and gay English authors D.H. Lawrence and E.M. Forester. Carpenter’s relationship with Merrill reportedly inspired the gay romance in Forster’s posthumously published novel Maurice and the straight romance in Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, both of which involved people in romantic relationships with men from lower social classes.

Beyond the couple’s notoriety, Carpenter himself is also celebrated for being a socialist whose early works opposed environmental pollution, cruelty to animals, worker exploitation, and other positions which have since become mainstays of different social justice movements.

Merrill died in 1928. In May of the same year, Carpenter had a paralytic stroke. After 13 months, Carpenter too died.

The men’s gravestone reads, “Do not think too much of the dead husk of your friend, or mourn too much over it, but send your thoughts out towards the real soul or self which has escaped-to reach it. For so, surely you will cast a light of gladness upon his onward journey, and contribute your part towards the building of that kingdom of love which links our earth to heaven.”