What’s your favorite Yiddish word? Along with Why aren’t you married yet?, it’s among my most dreaded questions. There’s a heavy implication that my answer should be something funny or—God forbid—colorful.

I’d much rather talk about my least favorite Yiddish words, of which there are a few. Farglivert, or congealed, is at the top of the list. Even the thought of it is slightly discomfiting, neither solid nor liquid, farglivert. I was gratified to find that translator Daniel Kennedy has his own problem with the word, and how difficult it is to translate properly.

Right behind farglivert is geshlekht, meaning sex or gender. Feels weird to say that I hate the word sex. But in Yiddish, dos geshlekht (sex) has the word shlekht (meaning “bad”) right up front! Not to mention that it is an extremely unsexy word to say. For years I assumed geshlekht and shlekht were related, a linguistic remnant of some medieval prudery. However, despite being almost identical, it turns out the two words are completely unrelated.

Geschlecht means sex in modern German, too, and it shares a common ancestor with the Yiddish in Middle High German. What’s interesting, though, is that today, the German geschlecht has a much broader semantic field than the Yiddish, including “group” concepts such as race, lineage, and dynasty. That the Yiddish word minds its own business and sticks to sex is frankly something of a relief, and makes me hate dos geshlekht a tiny bit less.

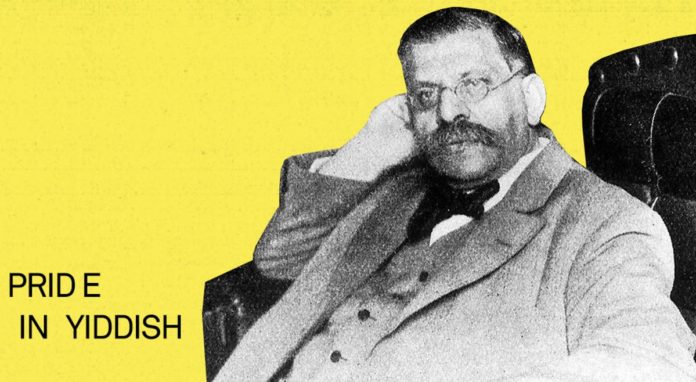

Geschlecht has been on my mind as I’ve been reading about Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935). Hirschfeld was a pioneer in the scientific study of homosexuality, founder of the first clinic to perform gender-affirming surgeries (100 years ago!), and a (sorta) openly gay activist for gay liberation. His title was sexologist, a job that seemed utterly fantastical to me when I read about it as a kid. Among his published work was the five-volume Sexology or, less pleasing to adult me, Geschlechtskunde.

You may not know who Hirschfeld was, but if you’ve ever seen a photo of a Nazi book-burning, it’s likely you’ve seen the destruction of his library without knowing it. In 1919 he founded and became the director of the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin. Within the institute, he collected thousands of books and materials related to his research, many rare and priceless. When Hitler came to power in 1933, he immediately issued an ordinance criminalizing any organization defending or arguing for gay rights. On May 6, Hirschfeld’s institute was stormed by a group of physical education students, members of Hitler Youth. They carted off thousands of Hirschfeld’s books and on May 10, 1933, the books were thrown on one of the Nazis’ first book bonfires.

In 1934, a special police task force was created to target homosexuals, the Reichszentrale zur bekämpfung der Homosexualität. According to historian George Mosse, this task force “made the persecution of homosexuals a priority of the state.” Further, in his Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe, Mosse writes that the “close connection between the persecution of homosexuals and the effort to maintain the sexual division of labor was demonstrated when the same team which combated homosexuals was given the additional task of proceeding against abortions.”

As Mosse further explains, the vilification of nonconforming sexuality was crucial to the working of Nazi propaganda: “All outsiders were to a large degree rendered homogeneous, but Jews and homosexuals, rather than criminals and the insane, were thought to use their sexuality as an additional weapon against society. Whatever the differences in their stereotype, they shared this special dimension of evil.”

In 1934, Hitler ordered the murder of the leader of the Sturmabteilung, the openly gay Ernst Rohm. His murder was ostensibly part of Hitler’s campaign against homosexuals, but in reality, it was his way of eliminating competition and/or opposition. After the murder of Rohm, Mosse tells us, “it was the turn of the Catholic Church to be brought into line through accusations of homosexuality against priests and monks.” Between 1934 and 1937, some 25,000 priests and others were accused. “Such accusations,” writes Mosse, “proved a powerful political weapon at the same time that they legitimized the new regime as a bastion of respectability.”

Hirschfeld had been on a world tour at the time of the book burning in 1933. Unable to return to Germany, he eventually fled to southern France, where he died in 1935. He was famous enough that his death was world news. Even the Tog, a fairly conservative Yiddish newspaper, carried an extensive and respectful obituary for Hirschfeld, detailing his many achievements, noting that his work in geshlekhtlikhe research had an enormous influence. The Tog, however, could not quite bring itself to print the word homosexual, instead speaking of Hirschfeld’s work to reform the laws around sexual crime. This was an oblique reference to Hirschfeld’s ceaseless effort to repeal Germany’s Paragraph 175, criminalizing homosexuality. (The code outlived the Nazi regime, and was only completely repealed in 1994.) They did, however, describe him as teaching that there was male potential within each female and vice versa.

This was likely a reference to Hirschfeld’s doctrine of “sexual intermediacy,” with each human a mixture of male and female attributes, in differing proportions. As Ralf Dose wrote in his biography of Hirschfeld, this doctrine “made fluid the border between male and female in an age that still made enormous and unbending distinctions between the sexes and their respective ‘natural’ attributes.”

Without an institution or students to carry on his legacy, Hirschfeld’s work fell into obscurity. But at least for a few years after his death, his name still had currency. Dose notes that after his death, Hirschfeld was still being flogged in the Nazi press as a “Jewish type.” And in 1937, he was named in Hans Diebow’s The Eternal Jew as “the most repulsive of all Jewish monsters.”

Hirschfeld turns up in a slightly more surprising place in November 1941. Writing under Yitschok Varshavski, one of his regular Forverts pseudonyms, Isaac Bashevis Singer published a long screed about the sexual perversions of Nazis, with repeated references to the work of Magnus Hirschfeld.

The headline is “The Nazi Army and Navy Is Full of Men Who Lead Disgusting, Abnormal Lives.” Bashevis opens by stating his view of male-female relations: Females, whether animal or human, will always choose the strongest male and a human male must distinguish himself in some way while the female waits patiently.

But experience proves, he says, that “in times of war, upheavals return the masses to their ancient instincts.” Not only does war bring out man’s cruelty, he writes, “but for a large portion of women, war causes them to lose every shame, every control,” abandoning themselves to wantonness. Bashevis cites one of Hirschfeld’s books (though he never says which one) supposedly showing how during WWI, German women lost all sense of morality. And as much as the German soldiers exhibited a wild barbarity, so did the German women show their own depravity. He cites a different scholar to show that “German farm women literally raped Russian and French war prisoners.”

He goes on to say that “it’s a known fact that Hitler, Goering, Goebbels, Hess and the other present day Nazi leaders are homosexuals.” In fact, he says, Rudolf Hess’ bizarre flight to England is easily explained. Hess was actually Hitler’s vayb (wife) but they had a fight and Hess did what women do after a fight: pitched a dramatic fit and pretended to leave.

It goes on and on like that. Hirschfeld is invoked again in regard to the gay men who wanted to serve in the German army and Hirschfeld’s involvement in evaluating their cases. Hirschfeld had an interest in proving that homosexuals were just as manly, just as patriotic as any other. He wanted the larger society to see homosexuals and other sexual minorities as fully human, and fully German. The point of Bashevis’ screed, however, is to paint the German military as full of homosexuals and thus, full of depraved men, all of whom have nothing to lose. And it’s not just men. He goes on another long tangent about women who disguise themselves as men in order to go to war. German women, he says, are especially known for doing this, as they have a drive to battle. The whole thing is so grotesque, so lurid, it starts to read more like a Penthouse letter than a Bintl Brif—though the second part of the article is actually printed on the Bintl Brif page.

The piece was written in 1941 and, of course, it’s obvious that those watching helplessly from America would be searching for ways to vent their rage at Hitler’s demonic rampage. But from my own standpoint of 2022, it’s a truly stomach-turning read, an attack on the right people (Nazis) using the innocent and well-intentioned as rhetorical ammunition.

There are, however, some kernels of truth hidden among the steaming heaps. As historian Elena Mancini explains in Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom:

Hirschfeld, in fact, helped thousands of homosexual men and women, transvestites, and heterosexual women to enter the war by instructing them on how to pass as a “normal” soldier. His Sittengeschichte des Weltkrieges (Sexual History of the World War), a two-volume compendium on wartime sexual mores that he edited, is rife with accounts on how male and female homosexuals successfully passed as male soldiers. Although women were officially allowed to serve, they were banned from the front. Hirschfeld openly argued the legitimacy of their service. In many cases in which homosexual activity was discovered in the military, Hirschfeld intervened, with success, on those soldiers’ behalf to mitigate penalties.

The opening of WWI saw Germans swept up in pro-war, pro-military excitement, and Hirschfeld was no exception. He’s a fascinating figure and deserving of our attention as a pioneer in LGBTQI research and activism. He was also very much a man of his time, as recent scholarship has shown. Like all people, he was complicated. Indeed, Bashevis, himself a very complicated person, closes his Forverts piece with one thing I agree with:

Lang konen mishugoyem di velt nisht firen

The mishugoyem can’t rule the world for long

Pride in Yiddish: Sure, we all know about Yidl mitn fidl’s cross-dressing adventures. But there’s a lot more to Yiddish drag, as demonstrated by Digital Yiddish Theatre Project’s terrific Yiddish drag timeline. If you want to go further in depth, Zachary Baker writes about two intriguing occasions when The Dybbuk was staged with the lead male role, Khonen, played by a female actor.

ALSO: YIVO’s Yiddish Civilization Lecture Series is underway and the offerings are fabulous and free. It’s hard to choose among so many great programs, but I’m especially excited about my friend Sonia Gollance’s talk about Tea Arcizewska’s play Miryeml and Yiddish women playwrights. July 14 at 2 p.m. … Tsvey Brider and Baymele are on tour together. Tsvey Brider is a duo featuring Dmitri Gaskin and friend of the column, singer-composer Anthony Russell. Baymele is a Bay Area trio, also featuring Dmitri Gaskin. Upcoming dates include the Yiddish Book Center’s Yidstock on July 10 and Brooklyn’s Jalopy on July 12 … Yugntruf’s weeklong, Yiddish-only retreat, Yidish-Vokh, is open for registration. Located in beautiful Copake, New York, Aug. 17-23 … Have you written and recorded a new Yiddish song between September 2021 and today? You can now submit it to the Bubbe Awards. It’s sort of like the Grammys for new Jewish music. The categories are: Best New Yiddish Song, Best Original Partially Yiddish Song, Best New Klezmer Instrumental Theme, and Best Jewish Music Video. Deadline for submission is July 31.