The debate over how best to approach people who identify as transgender or non-binary is many-layered and can be complex. Medical questions about the evidence for the safety and efficacy of specific interventions, and the ethics of treating minors, deserve thoughtful and open discussion. The optimal way to incorporate transgender athletes into competition also could benefit from a good faith debate.

Unfortunately, discussion around transgender issues suffers from at least two sources. First, it has been coopted as part of a politically-motivated culture war. This reality is exactly the opposite of thoughtful good-faith discussion. Second, for most people wrapping their head around a reality that may not conform to traditional notions of strictly binary sex and gender takes a lot or processing. Misconceptions about the basic science are rampant, and are, in fact, encouraged by the culture warriors.

Many of those who are pushing back against trans healthcare and broader acceptance are explicitly premising their position on the claim that biological sex is strictly and obviously binary. They portray themselves as taking the scientific high ground, and anyone who questions this obvious biological fact are the ones engaged in pseudoscience.

For example, in a recent article by James Lyons-Weiler (Biology is the biology is the biology, he begins:

“Most of us are born male of (sic) female. This is not our “assigned gender”: it’s our biological sex. An individuals’s sex is determined in animals (and plants) via the chromosomes one is born with.”

Wrong, right out of the gate (as I will detail below). He goes on:

“For most of us, we ARE male, or we ARE female. Unfortunately, early scientific articles conflated “gender” and “sex”, and much of society conflate them this as well. Depending on context, someone might need to know your sex (karyotype).”

He is saying that sex is strictly binary, it is entirely determined by karyotype, and it is completely distinct from gender. While these views are common, especially among those who are critical of the trans identity, they are also demonstrably scientifically wrong.

Biological Sex Is Not Binary

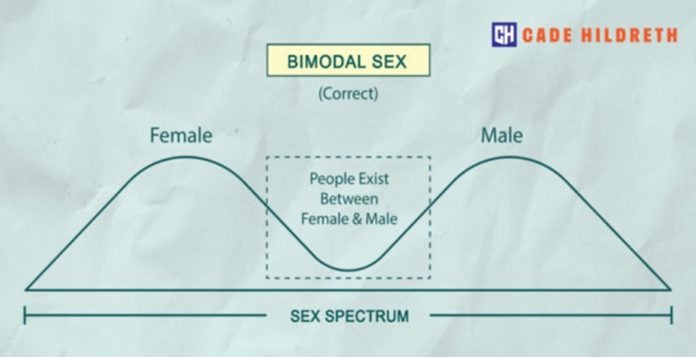

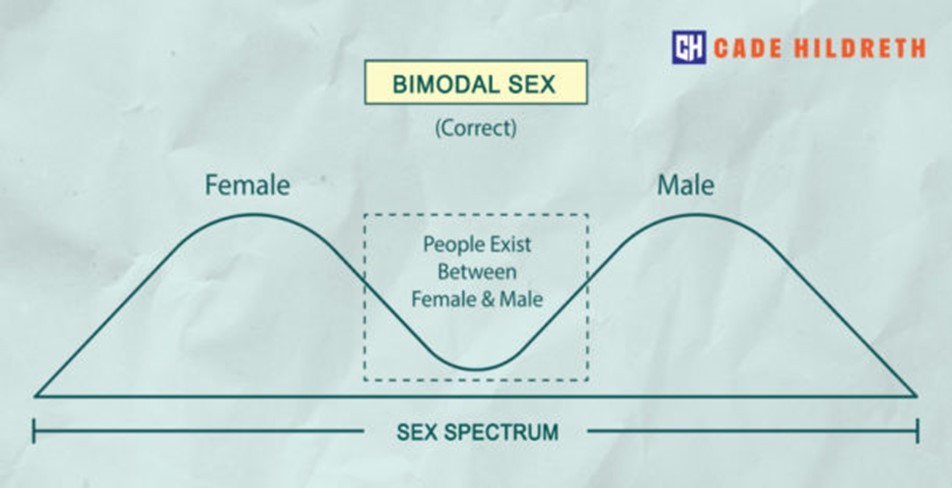

The notion that sex is not strictly binary is not even scientifically controversial. Among experts it is a given, an unavoidable conclusion derived from actually understanding the biology of sex. It is more accurate to describe biological sex in humans as bimodal, but not strictly binary. Bimodal means that there are essentially two dimensions to the continuum of biological sex. In order for sex to be binary there would need to be two non-overlapping and unambiguous ends to that continuum, but there clearly isn’t. There is every conceivable type of overlap in the middle – hence bimodal, but not binary.

This matters, and in fact it is the overlapping middle that is the very point of the discussion. Denying a trans identity is denying that overlapping middle. Let’s review the biology of sex to see what I mean.

It is absolutely true that humans display sexual dimorphism, with a typical male and typical female set of traits. There is no third sex, or pole, or sexual archetype. This can be distinguished, for example, from body type which is understood as trimodal – ectomorphic, endomorphic, and mesomorphic – forming a triangle with individuals falling somewhere between the three poles. Biological sex has only two poles, with one axis of variation between them. (See the main image for a good visual representation of binary vs bimodal.)

It is also true that most people tend to cluster around one of the two poles of biological sex. So at first glance, looking superficially at the human population, it may seem binary. This is because binary and bimodal can look very similar if you don’t dig down into the details. So let’s do that.

First we need to consider all the traits relevant to sex that vary along this bimodal distribution. The language and concepts for these traits have been evolving too, but here is a current generally accepted scheme for organizing these traits:

• Genetic sex

• Morphological sex, which includes reproductive organs, external genitalia, gametes and secondary morphological sexual characteristics (sometimes these and genetic sex are referred to collectively as biological sex, but this is problematic for reasons I will go over)

• Sexual orientation (sexual attraction)

• Gender identity (how one understands and feels about their own gender)

• Gender expression (how one expresses their gender to the world)

Let’s start with genetic sex. This may seem like a home run for binary sex, with females being XX and males XY, but on closer inspection this is not true. Again, yes, most people fall into one of these two chromosomal patterns, but we also see other patterns, such as XXY, XYY, XXX, etc. Further, some people can be mosaics, with some cells having XX and others XY.

But I think even more important than these chromosomal states is the fact that chromosomes alone do not fully tell the story of the genetics of sexual dimorphism. There are a number of genes involved in sexual characteristics (not all located on the sex chromosomes), and they can vary dramatically within chromosomal sex types, and even among the cells in an individual person, and throughout one’s life. John Achermann, who studies sex development and endocrinology at University College London’s Institute of Child Health, characterizes the situation this way:

“I think there’s much greater diversity within male or female, and there is certainly an area of overlap where some people can’t easily define themselves within the binary structure.”

Another layer of genetic complexity is gene copy number. For example, XY individuals with extra copies of the WNT4 gene can develop atypical genitals and gonads, and a rudimentary uterus and Fallopian tubes.

Further still, genes alone are not the whole picture of biological sex. There are a host of epigenetic factors at play, including hormone levels at different stages of development, hormone receptor sensitivity, and metabolic factors. All of these influence the development of sexual characteristics, which can vary along a spectrum. For example, there are XY females who are chromosomal males but develop mostly or entirely female because of androgen insensitivity. There are, essentially, women walking around who have no idea they have XY chromosomes.

Let’s move on to the primary sexual characteristics, which are essentially the internal reproductive organs and external genitalia; for females that is ovaries, uterus, and vagina, for males it is testes, prostate and penis. Do these characteristics vary in a strictly binary or bimodal way? When it comes to gametes, these are strictly binary – egg or sperm. However, even here there are intersex individuals with “ovotestes”, some of which can make both eggs and sperm. But, it is fair to say when it comes to reproduction, the system is binary, but sex is about more than reproduction.

This is another concept that many people get caught up on, thinking in evolutionarily simplistic ways. The argument often goes that sex is only about reproduction, and since gametes are binary, sex in total is binary. This is incredibly reductionist, and misses the fact that traits often simultaneously serve multiple evolutionary ends. Sex, for example, is also about bonding, social relationships, power, and dominance. Think about this – what percentage of the time that humans have sex is the express purpose reproduction? How many people have no desire to ever have children, but still have an active sex life? Can there be romance without sex? Why are there so many aspects of sex that are not strictly reproductive?

Other than gametes themselves, other primary sexual characteristics are clearly bimodal but not strictly binary. Developmentally, the penis is the male correlate of the female clitoris. Both vary significantly in size, in rare cases meeting in the middle in what is called “ambiguous genitalia”. In some females labia may be partially fused into a scrotum. There is also no sharp demarcation for how large a clitoris has to be or how small a penis has to be in order to be considered “ambiguous”. Such conditions are also not uncommon. A 2000 review found:

“We surveyed the medical literature from 1955 to the present for studies of the frequency of deviation from the ideal male or female. We conclude that this frequency may be as high as 2% of live births. The frequency of individuals receiving “corrective” genital surgery, however, probably runs between 1 and 2 per 1,000 live births (0.1-0.2%).”

A 2015 review puts the estimate at 1.7%. Still, some may argue this is all not relevant to the question of, for example, gender identity. However, it establishes the complexity of sexual development, which results from not only chromosomes but a host of genetic and epigenetic factors, hormone levels, hormone receptor sensitivity, and metabolic factors. There is no one measure that by itself determines biological sex. And, most importantly, even within the subpopulation who have unambiguously male or female chromosomes, gametes, and genitals, there is considerable variation in their secondary sexual characteristics, which also vary in a bimodal and not strictly binary pattern.

Some secondary sexual characteristics are present from a young age while others emerge during puberty, and include bone structure, fat distribution, shape of the pelvis, muscular development, height, pitch of voice, and degree and pattern of hairiness. For all of these characteristics there are clusters of typically male or typically female, but these are statistical only with great variation within groups. For example, if the only thing you knew about someone was how tall they were, or how hairy they were, you would likely not be able to determine their sex. Men are statistically taller and stronger than women, but many men are shorter than or weaker than many women. I have less body hair than many women I know.

If what I have discussed up to this point were all there were to sex, I honestly don’t think the topic would be that controversial. All biological traits vary in a complex and messy way, and sexual characteristics are no exception (why would they be?). Most of the controversy surrounds sexual dimorphism and the brain. Again, here we see that there are statistical differences only, with greater variation within the sexes than between them.

One brain feature that gets a lot of attention, however, is sexual orientation. I know I am framing this with a conclusion that some people contest, that sexual orientation is essentially determined by brain development, but that is the current consensus of scientific evidence and opinion. People are generally born with their sexual orientation, even if it is not fully realized until they go through puberty. In fact, I would consider sexual orientation to be part of biological sex (which is why I divided up sexuality as I did above).

Especially before the science dealing with this issue was more mature, this was a controversial question. Those who opposed gay rights claimed (and some still claim) that homosexuality is a choice, or a product of social influences, perhaps even a mental disorder or pathology. Years of research has lead to the conclusion that sexual orientation among humans is simply more fluid than old-school strictly binary concepts. People are heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual (romantic feelings are blind to sex or gender), asexual, and everything in between. I don’t think that anyone can reasonable defend today the position that sexual orientation is strictly binary, and any deviation is pathological.

If, then (as seems clear), sexual orientation is a brain function largely determined by genes, hormones, receptor sensitivity, and other epigenetic factors all affecting brain development and physiology, then it’s reasonable to consider sexual orientation an aspect of biological sex also. In a 2018 commentary published in PNAS, neurobiologist Dick F. Swaab begins:

“Current evidence indicates that sexual differentiation of the human brain occurs during fetal and neonatal development and programs our gender identity—our feeling of being male or female and our sexual orientation as hetero-, homo-, or bisexual.”

What does this mean for our binary vs bimodal sex question? I think it makes it pretty clear that biological sex is not strictly binary, because we can see any combination of morphological sexual characteristics and sexual orientation – you can’t know someone’s sexual orientation by looking at their genitals.

This is where communicating these ideas gets tricky, because some experts might express this reality by saying that there are more than two sexes. I think this may be counterproductive conceptually. I prefer the “bimodal but not binary” approach. But understand the real point – a strictly binary definition of biological sex cannot possibly capture all of the actual variation, which includes many possible states of sexual orientation. You can also see, on the other side, that claiming there are only two sexes because “gametes” is hopelessly reductionist and poorly informed.

The situation gets more complex when we turn to gender identity. All the old arguments that were marshalled against homosexuality (that it is deviant, pathological, a choice, a social contagion) are now being applied to those with a non-traditional gender identity, and with just as little scientific basis. The scientific research is not as well developed as it is for sexual orientation, but what we have so far strongly suggests (just as it did in previous decades for orientation) that people are essentially born with their gender identity. Many people who identify as trans knew their gender identity from a very young age, similar to sexual orientation. The principle of parsimony would suggest gender identity is also a brain phenomenon, and therefore just another aspect of biological sex.

What researchers find when they simply describe gender in the population are people who display pretty much every combination of morphological sex, gender identity, expression, and sexual orientation. Gender identity does not appear to be binary at all, and does not even fall into categories as cleanly as sexual orientation. What we know is that a small percentage of the population does not identify with the sex that they were assigned at birth. Why would I say it that way? This too has become an issue of controversy, as if sex is an opinion. However, given everything I reviewed above, what is the alternative? “Biological sex” doesn’t work, because it probably includes gender identity, so that becomes self-contradictory. Sex is assigned at birth based entirely (in most cases – unless for some reason there was a genetic test) on examination of the external genitalia. Sure, because we are a bimodal species, this is a reasonable marker for biological sex for many people. But of course it does not capture all of the biological aspects of sex we reviewed (such as genetics and hormone levels), does not capture sexual characteristics that do not emerge until puberty, and does not capture anything to do with brain development and function.

To take the position that the gender assigned at birth is completely objective and unambiguous, the beginning and ending of biological sex, is to also believe that external genitalia as manifested at birth are 100% determinative of every other aspect of biological sex. But we know this not to be true. It’s definitely not true for secondary sexual characteristics, which can vary significantly, it’s not true for sexual orientation, and it’s not true for gender identity.

In practice, therefore, someone who is trans (or gender non-binary or gender queer) does not have a gender identity that traditionally aligns with their external genitalia (as it is apparent shortly after birth). This is no different than people who have a sexual orientation that does not traditionally align with their external genitalia. This is not at all surprising once we understand the complex messiness of sexual development. In my opinion, a reasonably thorough and objective review of the current scientific understanding of biological sex results in the unavoidable conclusion that human sex is bimodal but not strictly binary.

Some people, however, may accept the specific arguments but reject the conclusion with what I consider to be dubious logic. One approach is to say – what is the practical difference between bimodal and binary? Why should sexuality in any way be defined by the 2% (to use a representative round figure) rather than the 98%? But this misses the actual issue, which is how we think about the 2% – are they part of biological diversity or can we define them out of existence?

The point of promoting the fiction of strictly binary sex is that it eliminates the middle ground. There are two sexes and nothing in between. Anyone who does, in some way, fall in between is clearly an “aberration”. Further (and this is often the point) they claim that any conflict between genitals and sexuality must be a mental disorder. Given all the biological evidence, however, it seems unavoidable to conclude that human sexuality is bimodal, with lots of variation in the middle. From this perspective trans individuals are just one more manifestation of the full and demonstrably biological diversity that is human sexuality.

The other related approach is to pathologize the trans identity. Just as with homosexuality in decades past, this view holds that a trans identity must be pathological, because there are only two “correct” gender identities, the ones that traditionally align with one’s external genitalia. This position ultimately rests on either circular reasoning or a flawed appeal to nature (again, because gametes).

With homosexuality, the question of “nature” is easier to answer. Homosexuality exists pretty much in every animal species we examine and to similar levels. Some (like bonobos) have extremely high rates of homosexual/bisexual behavior. So it’s hard to argue that homosexuality is “unnatural”. There is no equivalent to gender among non-human animals, however. Because gender expression is so cultural, it is hard to scientifically examine what an animal’s gender identity might be. Inferring from sexual behavior would be difficult to separate from sexual orientation. (There is some interest in researching this question among primates, however.)

It is also possible to argue that sexual orientation, which is pretty clearly biological, may be phenomenologically different in nature from gender identity – that while sexual orientation is biological, gender identity is not. This is not impossible, and we do need further research to have a confident answer. But given what we do know the simplest answer is that gender identity is a brain function as much as sexual orientation is. Gender identity awareness is usually established by age 2-3, which itself is strong evidence it is biological. Further, the position that “gender identity is all psychocultural” should not be treated as the default answer, and it is not reasonable to place the burden of proof entirely on the biological side of the question.

We could also approach this question scientifically by looking at the brains of cis vs trans individuals to see if there is a difference. This research is preliminary, with mixed findings, but is trending in the direction of showing some differences between cis and trans brains. Overall studies do find differences in some measured features, with trans brains looking more like the identified gender than the apparent biological sex (even prior to any medical interventions). A 2015 review found:

A difference in brain phenotype of people with GI compared to natal sex controls in various brain measures suggests a sex-atypical development of the brain. However, it remains unclear whether these changes originate from prenatal organization alone. Knowledge of the development of the brain during adolescence (Giedd et al., 2012), and the importance of puberty in the clinical presentation of GI (Steensma et al., 2013), suggest that this period is pivotal in understanding the development of GI. Recent work that found subtle deviations in GM volume (Hoekzema et al., 2015), and brain activation during executive functioning from their natal sex (Staphorsius et al., 2015), as well as a response to a pheromone-like substance that was similar to their experienced gender in transgender adolescents (Burke et al., 2014), underscores the need to determine the timing and nature of sex-atypical organization.

“These results on brain structure are thus partially in line with a sex-atypical differentiation of the brain during early development in individuals with GD (gender dysphoria), but might also suggest that other mechanisms are involved. Indeed, using resting state MRI, we observed GD-specific functional connectivity in the visual network in adolescent girls with GD. The latter is in support of a more recent hypothesis on alterations in brain networks important for own body perception and self-referential processing in individuals with GD.”

Overall it’s too early to form a confident conclusion, but the data is trending in the exact same direction as similar research into sexual orientation – the brains of trans individuals appear to be different than their cis counterparts.

All things considered, I think an objective look at the science of biological sex indicates that humans are sexually dimorphic and bimodal, but that biological sex is much more complicated than it may at first appear and is not strictly binary. While we still need to do a lot more research to fully understand the trans / gender non-binary phenomenon, it seems that variations in gender identity are just one more manifestation of biological sexual variability. There is also no one system to categorize all of biological sex (do we use chromosomes, genes, hormone levels, genitalia, gametes?), and certainly humanity cannot be placed entirely into two categories. The binary system breaks down in the middle.