IN HER SUPERB new story collection Light Skin Gone to Waste, Toni Ann Johnson follows the Arrington family, starting in the not-so-distant world of 1962. From there, via parents Phil and Velma and daughter Maddie, we travel through the ’70s, ’80s, and up to 2005, along the way visiting the Bronx, West Africa, and New Jersey, but always firmly anchored in uptight Monroe, in Upstate New York. Each story is an emotional journey through the complexity of an upper-middle-class Black family attempting to live their lives in a virtually all-white community. The stories create an emotional resonance that continues to thrum long after the reader has finished the book.

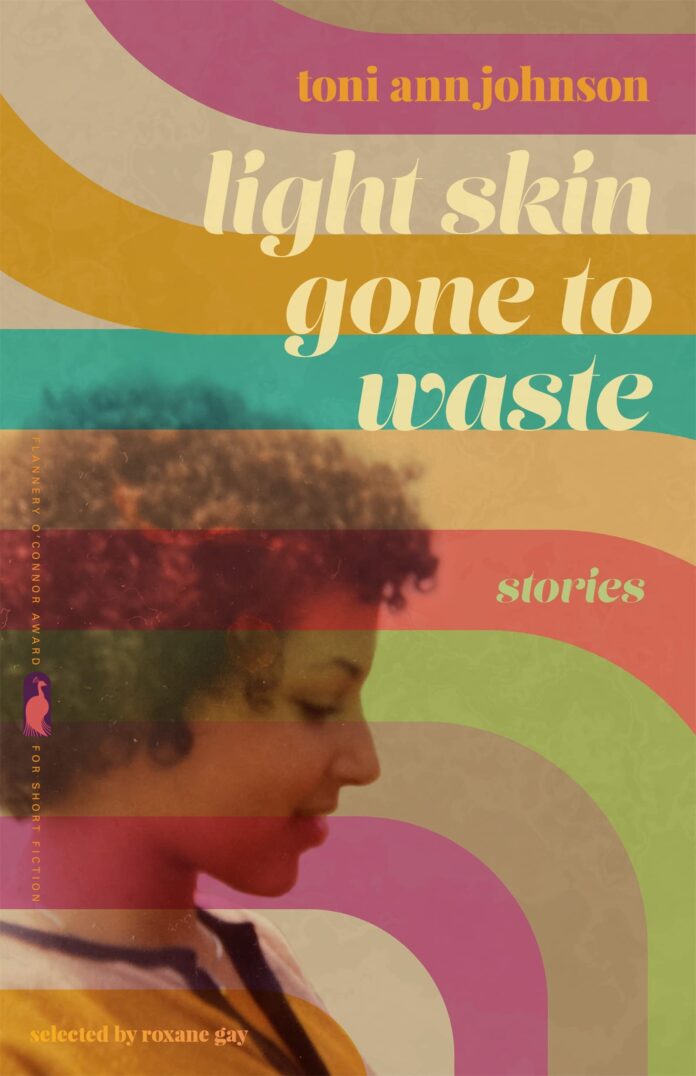

Toni Ann Johnson is an amazingly gifted writer with a long history of awards and successes, from being nominated for an NAACP Image Award for her 2014 novel Remedy for a Broken Angel to winning Accents Publishing’s inaugural novella contest for Homegoing (2021) to being a two-time recipient of the Humanitas Prize for her teleplays Ruby Bridges (Disney, 1998) and Crown Heights (Showtime, 2004). This collection, published by the University of Georgia Press, was selected by Roxane Gay.

We meet first Philip Arrington, a man who has decided he will transcend his race, whether or not the world at large agrees. He works in a mental health clinic. It is 1962, and he is about to rent a home in verdant Upstate New York, dressed nattily because, as his second wife Velma says, “Good grooming puts White people at ease.” For the first time during his 15-minute ride from Goshen to Monroe, Phil’s eyes have stopped scouring the road for Black drivers. He had hoped to see at least one, but with this view, it doesn’t matter anymore. If being a lone pioneer is what it costs to enjoy this small-town beauty, he’ll pay. He notes that his friendly greetings are shunned by the locals he passes, yet he continues on and ultimately rents the home, even after being told not to “expect the neighbors to welcome you with cakes or invite you to their barbecues.”

Phil is an educated Black man with a PhD from Yeshiva University and aspirations to open a private practice and live his life somewhere beautiful. Johnson’s title, Light Skin Gone to Waste, immediately signals internalized anti-Blackness, and in the opening story, we see Phil’s mother scolding him about the upcoming move: “Don’t wanna have to come up there and cut your big-shot britches down from a tree.” Meanwhile, his wife Velma reminds him that it’s Upstate New York, not the Jim Crow South.

But a brick thrown through his daughter’s window reveals the risks of his move. In response, Phil arms himself and, with a white friend, walks up and down his street while firecrackers go off around him. Enraged, he spies a lake shimmering in the distance: “If he does make it down, he plans to dive into that beauty and let it drown everything that smolders inside him.” He thinks that “what he wants to do is wake from this nightmare, this battle born from his audacity to start a life.”

Despite this cruel reception, the family remains in Monroe, ultimately buying a home. He may, by virtue perhaps of his education and charm, be able to navigate the predominantly white world, which he feels is his place, and leave the scrabbling and the misery to his Harlem-raised wife and his mislaid daughter Maddie. Phil is a smooth socializer, and Velma is a beauty: “[P]eople in Monroe expected Black women to look like Aunt Jemima and that’s why they were so amazed Velma was attractive.” But Maddie is the only Black girl in her class, and in her hometown, her skin color marks her as alien.

It’s Maddie’s heart we see pummeled. It’s her young life we begin to understand as incoherent, lost, and, worst of all, neglected. The racism of her world causes a childhood friend to abandon her. In seventh grade, during her first kiss, she has a heart-shredding epiphany about her boyfriend: “[W]hen […] cool girls with Farrah Fawcett wings and thin backsides would notice him, and boys with bowl haircuts would tell him the rules of the game, and before they even stopped kissing, she knew that she couldn’t compete.”

In addition to the constraints of the world at large, we witness the terrors of a dysfunctional family. In Monroe, both Velma and Phil are fleeing lives of neglect and trauma, reshaping their world into something gleaming and glittery: tennis clubs, antique shopping, modern art, international travel. Phil has a fondness for white women, and they have a taste for him. Later, when Phil admonishes his daughter to date white boys — as if somehow his success with white women is translatable — he reveals how completely disconnected he is from the isolation Maddie is enduring in the community he has chosen.

One of the most striking stories in this collection filled with them is “Lucky,” set in West Africa in 1972, where we follow eight-year-old Maddie through a series of misadventures with her parents. She watches them as they collide into cultural miscommunications in Senegal; then they travel to Côte d’Ivoire, where Maddie watches, from the back seat of their rented car, a Frenchman, white, in a police uniform, beat a Black African man with a club. It shocks and scares her, yet her parents drive by with no mention of it. How unsurprising that, as Maddie encounters the reality of African colonialism, her parents do not remark upon it. That violence has nothing to do with them! This compact story illuminates Maddie so beautifully: a brief moment of belonging, a deep feeling of exile from her family (particularly as her father rails against the fact that they had to bring her along in the first place), followed by an episode of profound and unconscionable neglect by her parents so intense that, as we near the story’s ending, we nearly weep with relief.

The power of these stories lies not only in their crisp and elegant writing but also in the growing horror of the unconscionable damage two self-involved adults wreak upon — or allow to happen to — their own daughter. While Velma seems, on the surface, to be impeccably poised, she is often inexplicably angry, and sometimes violently abusive, towards Maddie. When her ire is raised, she can even reveal her combat-ready Harlem upbringing to the neighbors: in response to a complaint about her dog, she growls, “Bitch: you and what brigade? You slap me, Sally, and I promise, that’ll be the last thing you do this side of the grave.” It isn’t until the collection’s second half that we hear from Velma directly — her contradictory voice, her unquenchable desires, her cracked heart. There are moving and enraging moments with her white housekeeper, prompting Velma to observe that “[e]ven White trash likes to have somebody they can feel better than.”

Johnson gives us fully realized characters with complex identities, negotiating often very painful episodes. Phil and Velma, who have endured their own generational tragedies, are now visiting their traumas on their daughter and each other. Yet as self-involved and oblivious to Maddie’s needs as they can be, each has a moment of surprising compassion — but these are moments that, alas, Maddie is not present to witness. Johnson fills the stories with the small details — a crappy piece of sculpture from Phil’s lover, an unexpected babysitting gig — that resonate as emblems of betrayal and loss.

Light Skin Gone to Waste is a brilliant collection that fully demonstrates Johnson’s craft and artistry. It is a tale of racism, victimization, and narcissism told with wit and beauty, and it takes the reader on a rich emotional journey, ending on a stunning moment of compassion and grace.

¤