Photo: Liz Hafalia/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

When Jeannie Crowley came up with the idea for a student-run repair center at Fieldston, a private school in the Bronx, she viewed it not only as an opportunity for students to gain technical skills, but also to learn to think more critically about consumption and the environmental toll of replacing devices instead of fixing them. In 2015, as the school’s technology director, she launched the Restart Center: a tutoring program where students could bring their broken devices and learn how to repair them from other students and professional technicians. Armed with replacement parts made by original-equipment manufacturers (i.e., the manufacturers that companies like Apple contract with to produce parts), students set to work on tasks like replacing their cracked phone screens.

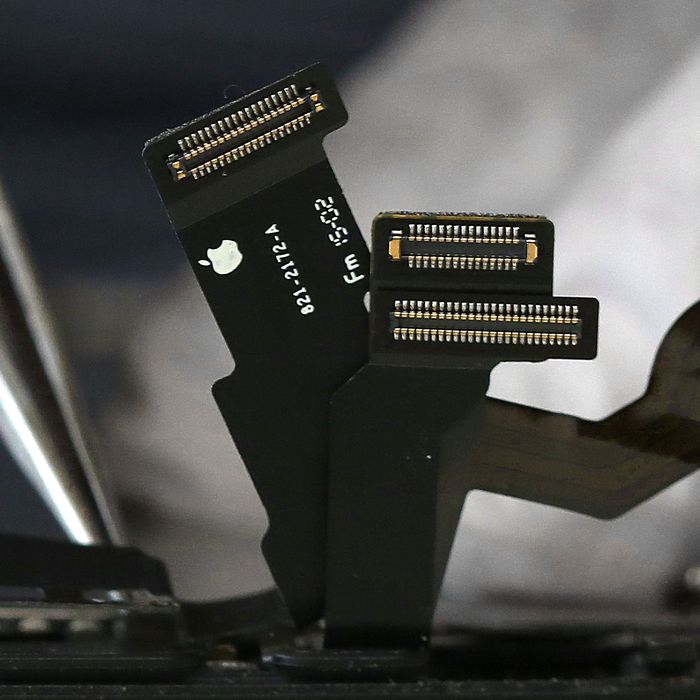

And then, she says, new phone designs nearly killed the program. When the iPhone X came out in 2017, replacement screens more than tripled in price, and manufacturers were often out of stock. Each new feature, too, seemed designed to make the phones more difficult to repair for anyone outside of Apple. On some models, for instance, replacing the screen disabled features like True Tone (which automatically adjusts the display’s color) and auto-brightness, even if the replacement screen was a genuine Apple part. According to Crowley, her students noticed how these changes discouraged independent repair, on top of design practices like assembling smartphones using adhesives.

“We noticed year over year that our ability to repair devices started falling off,” she said. “And some devices were just too difficult, too expensive, or the parts simply weren’t available for us to make repairs.” Before long, her students felt trapped in a “cat-and-mouse game” with Apple. The company developed new methods of making its devices more difficult to repair as soon as the students had conquered the previous obstacles.

That game is one that’s familiar to the international right-to-repair community — a diverse array of repair-shop owners, DIYers, farmers, and climate activists organized around the principle that consumers should be allowed to fix the products they own without interference from the companies that make them. In the early 2010s, as machines from tractors to cell phones grew more complex and companies developed new methods of disincentivizing independent repair, the community coalesced into a political movement referred to as “right to repair.” At the local level, the community hosts events like repair cafés where people can bring their broken devices and help each other fix them. Nationally, the community is supported by resources such as iFixit (a site that provides detailed repair guides and replacement parts for devices) and activist groups like the Repair Association, which has led the U.S. push for right-to-repair legislation, prioritizing state legislatures as a key battlefield.

Those efforts may soon pay off in a big way, as New York is on the verge of passing right-to-repair legislation that would be the first of its kind in the country. Dubbed the Digital Fair Repair Act, the bill centers microchip-powered devices such as smartphones, tablets, and laptops. Taking cues from draft legislation written by the Repair Association, the law would require manufacturers to supply consumers and independent repair shops with the tools, parts, and manuals required to fix their devices at a reasonable cost, effectively democratizing resources that manufacturers increasingly restrict to their own repair networks. To its supporters, the fact that the bill received bipartisan support in Albany offers further proof of the right-to-repair movement’s broad appeal — as a cost-saving initiative for consumers; a lifeline for independent repair businesses; and a step toward reducing e-waste, a fast-growing and notoriously toxic waste stream.

Among those who stand to benefit the most from the legislation are independent repair-shop owners, who have to navigate a different maze of unfriendly design features for every product they work on. Apple, Google, and Samsung, for instance, rely on a strategy called “part serialization,” which allows their products to cease certain functions when an unauthorized repair has taken place. (This is what Crowley’s students encountered when a screen replacement eliminated True Tone.) While larger corporate repair shops cut through some of the red tape by entering partnerships with device manufacturers, such arrangements are often out of financial reach for smaller businesses.

Justin Millman has experienced a version of that firsthand. As the owner of a repair shop in Westbury, New York, that specializes in servicing schools, he says he turned down a partnership with Acer after the company demanded “overly personal information” like his business’s balance sheets, his tax returns, and a credit application. “I said, ‘I don’t want credit from you, I’m not buying anything from you,’” Millman said. (In an email, an Acer spokesperson acknowledged the credit application but claimed to be unaware of “any requirement for tax returns or balance sheets.”) The bigger problem, Millman argues, is that manufacturers don’t produce enough replacement parts, incentivizing customers to “just upgrade next year” — an expensive proposition for Millman’s public-school clients and a damaging blow to his business model.

“Even the ones that try and play ball, they don’t produce the quantity for repairs,” Millman said. “They may say, ‘Well, we sell parts.’ But try and go buy 100 motherboards for a computer that has a known failure on its motherboard. It’s not possible.”

The New York legislation wouldn’t require manufacturers to produce more replacement parts, but they would have to be more transparent about what parts they do have, says Nathan Proctor, senior director of the Right to Repair campaign at U.S. PIRG, a consumer-advocacy group. In general, he says, the bill would compel manufacturers to think of repair as an open ecosystem where they can’t obscure as much information. “They will face tougher questions and higher expectations,” Proctor says. “The OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] clearly view the right to repair as the expectation that repair will be available, and I think they are right to do so.”

While manufacturers might view right-to-repair legislation as an inevitability, their aggressive response to the New York bill indicates that they intend to at least delay it and to minimize its eventual impact. Some version of a right-to-repair bill has floated around Albany for almost a decade, but when the current iteration gained momentum in the Legislature back in May, lobbyists sprang into action. “Opposition that we really didn’t know about came out of the woodwork,” said Assemblymember Pat Fahy, the bill’s Assembly sponsor. “Overnight, we had an inch thick of opposition memos.”

Most of those memos, Fahy said, came from companies like John Deere, Caterpillar, and General Electric. In its original form, the Digital Fair Repair Act was far more expansive, covering everything from microwaves and refrigerators to lawn mowers and tractors. After a flurry of lobbying this spring, those products were removed from the legislation altogether. The farming-equipment carve-outs proved particularly disheartening for New York farmers, who continue to raise the alarm about how companies like John Deere and Caterpillar use software locks to prevent owners from handling simple repairs themselves.

“That puts us in a hard spot, because a lot of these companies don’t have enough technicians to cover all the equipment that they have out there,” says Kim Zuber, a dairy farmer in western New York who has advocated for right-to-repair legislation through the New York Farm Bureau. He says an equipment failure during the brief window for planting or harvesting feed crops for his farm’s 3,000 cows can be financially devastating — a situation that’s worsened by having to wait around for a company-certified technician. “Fortunately we have multiple tractors, so when one goes down, we got others to work with,” he says. “But that’s not true for everybody.”

While Fahy regrets having to whittle down the bill, she argues it would have died entirely if they hadn’t removed the farming-equipment issue. “We had no choice if we wanted to move the bill,” she said, noting that the surviving consumer-electronics portion affects more New Yorkers than the tractor component. “I didn’t take the bill to sit on it for another ten years.”

In its current form, the bill sailed through the Legislature with near-unanimous support and now awaits a signature from Governor Kathy Hochul. Even so, the manufacturing lobby hasn’t given up. In October, the Albany Times-Union reported that powerful tech-industry members like Apple, Microsoft, and the trade association TechNet have focused their lobbying efforts directly on the executive branch. The governor’s six-month delay in signing has raised the specter of a potential veto, but the bill’s advocates largely remain confident that she’ll sign it.

If the bill becomes law, Proctor argues it would set a “new floor” for the right to repair in the U.S. If she doesn’t, he admits it’d be a “major setback,” but adds that he doesn’t think that even manufacturers believe they can defeat the movement. Apple, for instance, began selling home-repair kits and replacement parts for some of its devices in April. (Notably, the cost of buying an iPhone screen and renting Apple’s official tool kit comes out to more than simply paying for Apple to replace your screen.) Although right-to-repair advocates welcome these concessions, they argue they’re not a replacement for legislation, and that consumers’ right to repair shouldn’t be left up to the whims of corporations. In 2021, John Deere fueled that argument when it failed to follow through on its promise that the company would make repair tools and diagnostic software available to the masses.

Proctor called the move a “stall tactic,” but corporate jockeying has yet to derail the movement’s legislative momentum. At least 41 states have proposed some form of right-to-repair legislation, and in June, Colorado passed a repair law pertaining to power wheelchairs. Right-to-repair activists hope that future state laws will eventually have an effect similar to a 2014 Massachusetts law that codified rules around automobile reparability, and later established a new industry standard for how manufacturers distributed diagnostics and repair information to independent mechanics.

While the manufacturers continue to raise concerns about being forced to share “proprietary” information, Repair Association executive director Gay Gordon-Byrne points out that the New York legislation only compels them to share resources that are already available to branded repair entities. Manufacturers have also raised concerns about the safety of independent repair. Dusty Brighton, a political strategist representing tech manufacturers’ concerns as executive director of the Repair Done Right coalition, argues that “legislating one-size-fits-all repair rules for manufacturers will compromise the safety and protections consumers expect.” Similar concerns were roundly dismissed in a 2021 report by the Federal Trade Commission, which found that manufacturers “provided no data to support their argument” apart from one example of someone’s phone overheating in Australia in 2011 after a third-party battery replacement.

Despite manufacturers’ ongoing lobbying, Representative Joe Morelle — who has proposed a federal bill similar to the New York legislation — thinks that even manufacturers will eventually want federal right-to-repair regulations. “If you start to have many laws like this and they’re all different,” he said, “I think even the OEMs are going to ask for national legislation so they don’t have a patchwork of different laws, where in each state they have different regulations.”

Crowley — who no longer works at Fieldston but hopes to start a similar repair program in her job with the Scarsdale public-school district — argues that what’s at stake with the right-to-repair movement is a once-hallowed tradition of American innovation. “A lot of people building things in America built things when they were encouraged to open things up, tinker, reverse-engineer things,” she said, pointing out how manufacturers’ unfriendly designs and sternly worded warranties discourage her students from doing the same. “I want them to be sustainable innovators, but I don’t even know if there are going to be innovators at all.”