Pakeezah and its central actress Meena Kumari are standing emblems of queer culture in India today. The immediate question to ask is, how can the story the generational love story of a courtesan betrayed in love, played by a woman in a heterosexual marriage that saw massive media scrutiny, have anything to do with the pulse of queer politics in a country like ours. The answer for the same lies in realising queerness as existing beyond pathological orientations and rather as a state of being – something that combines an abiding sense of politics and aesthetic pleasure.

It should be of little wonder that for years on end now, the woman who told a pleading lover “raat gayi baat gayi” after a torrid one-night stand would be anything short of a gay icon in a country like India. Gays who bloom into their dollhood in a post-377 India will be little aware of the extents to which criminalisation of identity could push people to make secret, expressions of their deepest desires and longings. Even today, the queer community is largely dominated by men with repressed notions of sexuality – who choose to seek comfort in the forbidden secrecy of one-night stands with men who would ghost them on a sea of apps the very next morning.

Queerness, especially in a country like India, is largely characterised by cultural trappings of seeing the queer experience as little beyond a campy aesthetic. More than freedom of expression, longing and pining have been registers of queer desire in our country which has demonstratedly been proved to bloom best in exile or secrecy. Such situations are even more problematised by the existence of national cultural icons like Meena Kumari with whom an entire section of the population comes to identify.

The creation of Pakeezah itself was a phenomenon for its audience to reckon with. Fourteen years in the making, the film was supposed to be Kamal Amrohi’s monument to the persona of Kumari herself. Meena Kumari, who agreed to do the film, at the cost of a singular guinea, also underwent separation from Amrohi himself over the course of filming. The last film to be released during her life, the latter years of shooting for the film had Kumari appear erratically on set due to her growing alcoholism. What greater registers of identification would gay men (basking in the knowledge of their constitutional criminality) need?

Subscriber Only Stories

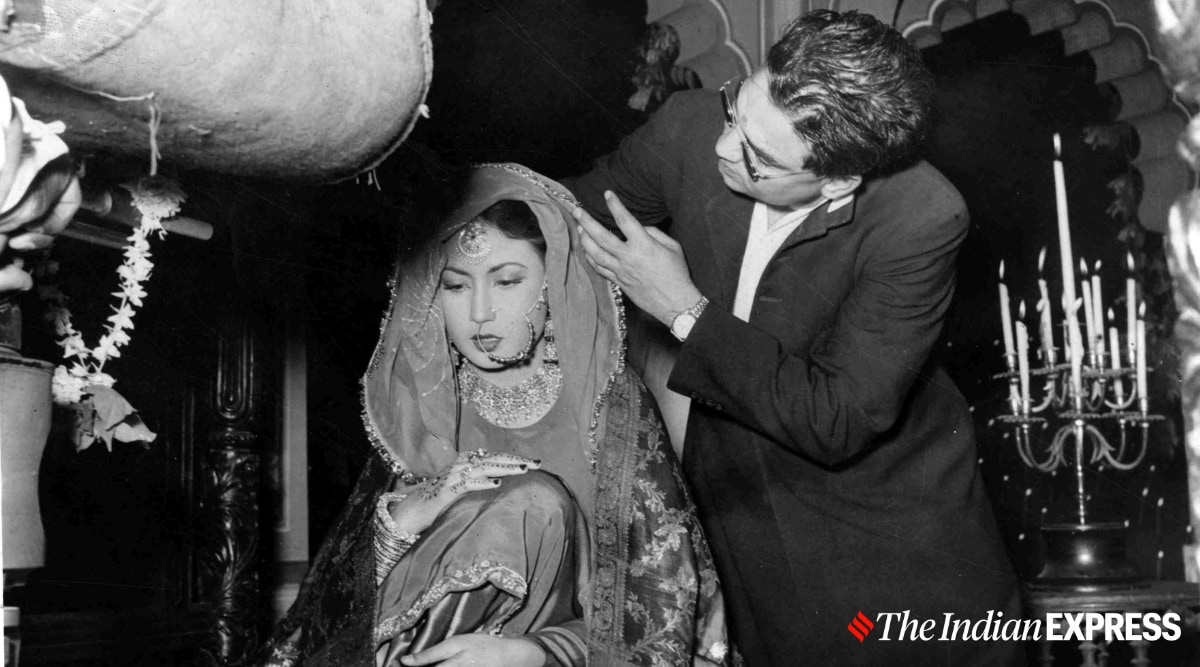

Meena Kumari on the sets of Pakeezah. (Photo: Express Archives)

Meena Kumari on the sets of Pakeezah. (Photo: Express Archives)

Sample Guru Dutt’s magnificent Saheb Bibi Aur Ghulam, where Kumari played the role of the iconic Chhoti Bahu. In a paean to the fading days of landed feudalism in our country, Meena Kumari immortalised the largely meta character of the wife who drowns herself in substance abuse and the company of a younger man, while her husband chooses the company of a courtesan. The classic Na Jao Sayiyan Churake Baiyan is filmed entirely on Meena Kumari herself. Dutt fills his frames with extreme close-ups of the actress’ face. We see her quivering lips as she urges her lover to not desert her. She is clearly under the influence of alcohol and her eyes flicker. Yet in that fleeting moment there is a presence of abject desire that is unmistakeable to the queer eye. The song itself never veers into the sexual (although there is a high incidence of masochism in the same), but Kumari performs it in monochrome to a campy pitch of perfection. It is a performance in every sense of the word – her hair goes all over the the frame of her body and our screens, her bangles travel up her plump arms and her eyes flicker. Yet there is pain in her eyes. It is Kumari and her juggling of the desire and pathos that makes her the most astute embodiment of queerness in the cultural currency of our country.

Beyond drag parties and pride parades and the sheer sequins of Zeenat Aman and feathery boas of Hema Malini, queerness too has been about the erotic that is fused with an abject sense of the pathetic. The expression of a desire that is inexpressible, especially in a society that has no vocabulary to understand the same, offers a two-fold understanding of the same. The first is to see desire as something so explosive that it inspires a literal death drive in the self. For Chhoti Bahu, this drive becomes apparent in the end of the song itself, where she ends by confessing that the pursuit of her passions would cause her to either live or die at his feet.

In Pakeezah too, the burgeoning nature of this desire takes form in overt instances of masochism. Sample the song Teer-e-nazar. The melody is an echo of the earlier song Chalte Chalte. That song was about the beginning of a relationship. A clarion call of sorts. Nothing short of a declaration of love. But in the finale song of the film, this song assumes different connotations. The idea of the feet are still present. There, the feet were to facilitate walking together through life. But here the feet, as they deliberately dance on shards of broken glass, become a site for self-inflicted pain that becomes the alternate in the absence of eliciting pleasure out of your own unfulfilled desire.

It is at this point that the pathetic enters the scene. We realise that the last song has been laced with images of violence all along. The name itself bears hints of images of archery and hunting, followed by (my favourite) the phrase zakhm-e-jigar. This is probably Bollywood’s earliest visualisations of the phenomena of zakhm kahin lagta hai, par dard kahin aur hota hai (the wound is one place, the hurt/pain in another). While the song itself talks about a wounded, or rather ailing heart, it is the feet which quite literally become deliberately wounded – thereby becoming an external manifestation of the internal ailment of the heart.

Kamal Amrohi and Meena Kumari on the sets of Pakeezah. (Photo: Express Archives)

Kamal Amrohi and Meena Kumari on the sets of Pakeezah. (Photo: Express Archives)

In a way, this singular sequence becomes a cultural reminder of the thousands of nameless men who gave up their lives in the face of societal ostracisation. Of all the men who fell in love with men who were straight or who would never transgress hetero-normative boundaries for a life of queer desires. Despite the aesthetic trappings of such a projection of excessive, all-consuming desire, these films of Kumari, also dubbed as The Tragedy Queen of India, touched one emotionally.

The well of alcoholism Chhoti Bahu descends into or the source of Sahibjaan’s pining and longing for Salim is a reckoning of their own deep rooted loneliness. Chhoti Bahu stands abandoned by her husband and Sahibjaan is denied marital bliss due to her status as a courtesan. Loneliness and unfulfilled desires hence become registers of queerness in a country on the brink of globalisation – where consumerist product adverts will soon dangle the image of happy conjugal lives to drive home ideas of consumption. And that is where Kumari steps in with her body of work.

It is in her that we trace the lineage of Chandramukhi from Devdas who speaks of a joyful passion that threatens to kill. Of Silk from The Dirty Picture, who chooses a Cleopatra-esque end to her career in an attempt to find a semblance of dignity through a profession built on her indignity. But despite the bleakness of modern queer politics in app-driven hook-up cultures, Kumari’s fictional tragedies hold little light to the larger triumph of her own career. Despite several attempts, Amrohi could never re-cast Meena Kumari, who ultimately over 14 years of stardom shot the film to completion. But is it truly then his monument to her? Or is it little more than monument of her own construction to the longing desires and sighs of queer lifestyles steeped in excesses? Methinks, the closing couplet of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 bears the only viable answer to that!