Best told Armstrong that he had informed a few other Republican activist types about these incidents and was confounded by their nonchalance. “Big deal,” he said was the reaction of Egil “Bud” Krogh, head of the Nixon Plumbers unit. “There were lots of gays in the Nixon administration too.”

At one point in the spring of 1980, Best said he confronted Deaver over lunch about Hannaford’s proposition. “It’s your partner and you ought to know,” Best told him.

“Who else knows?” Deaver asked.

“I told two groups,” Best said he replied. “Those I needed to talk to and those I needed to protect me.”

Deaver, Best said, evinced no reaction as he continued eating his lunch. “You could probably keep eating if I told you that World War III had started,” Best said he remarked, adding that Kemp as the VP pick would be a “giant mistake,” an assertion with which Deaver apparently agreed.

Best also told Armstrong about the man, a then 17-year-old volunteer on Reagan’s first gubernatorial campaign named William Seals Jr., who claimed to have had sex with Reagan. Best said Seals told him the encounter took place on the night of Reagan’s first inauguration in Sacramento. Reagan, wearing nothing but a bathrobe, had invited Seals into his hotel suite. “If Reagan is elected president,” Best said Seals boasted to him, “I could be first lady.” Seals further asserted that he had participated in the alleged Lake Tahoe orgy and had “gone to bed” with Kemp. Despite his best efforts, Armstrong was unable to track down this elusive figure, and Best and Seals have both since passed away.

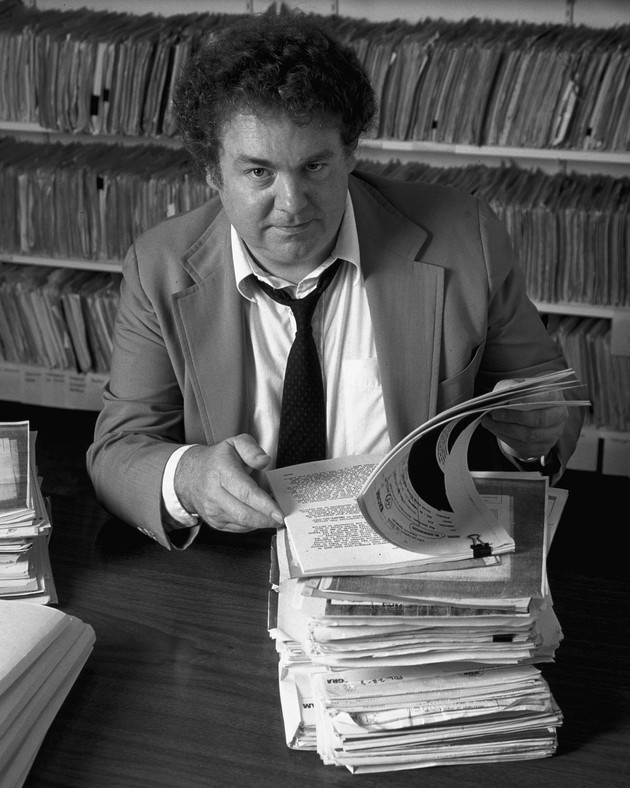

The essence of Best’s allegations, Armstrong wrote in a memo to his colleagues, was that submission to the sexual demands of an influential circle of gay men was “the sine qua non of success in the Reagan organization.” Best, he wrote, was “sane, sober, careful and restrained,” not “flaky or kooky.” In appearance, he was “sort of Calif. Preppy (Woodward as beachboy)” and “probably jail bait when he was in his early 20s.” But Best also struck Armstrong “as a man who has seen a flying saucer on two separate occasions and can’t get anyone to believe him,” which left the reporter with the feeling that the story lacked legs.

“Count me out until someone on this list [of alleged homosexuals] is actually serving in a presidential administration with access to national security information or until a more current pattern of some group is evident,” Armstrong concluded.

Reporter Ted Gup tracked down Bouchey in a depressed suburb outside Dallas, where the think tank director was with his wife and children visiting his father-in-law at his mobile home. Bouchey was “shocked” that a Post reporter would come all the way to interview him, Gup later wrote in a memo, but he agreed to speak outside, in the 112-degree heat, away from his family. As Bouchey described the events of June 25 and 26, he reenacted for Gup the moment that sent Livingston fleeing to the basement of the Rayburn Building, grabbing Gup’s “knee and thigh firmly” in a “quick unexpected action.” (“His hands were strong,” Gup recounted. “I thought, ‘My God, if he grabbed Livingston that way, no wonder the guy spent the night in the gym.’”) As for ordering “hits,” Bouchey unreservedly denied that “any of his contacts were terrorists or violent,” and he expressed bewilderment that Livingston had felt fearful for his safety. He was less surprised, however, about the suggested existence of a “gay network” surrounding Reagan.

“He didn’t laugh at the idea,” Gup wrote. “He took it seriously. He did not question the legitimacy of a reporter inquiring into it.”

Bob Woodward interviewed Livingston, whom McCloskey had apparently not bothered to consult before relating their conversations to the Post. “I’m petrified and paranoid about this,” Livingston said, according to notes taken by Woodward, who wrote that there was “lots of pushing necessary to get him to talk.” Woodward repeatedly declined to speak with me about these events.

According to Woodward’s notes, Livingston disputed McCloskey’s characterization of his early morning phone call from the House gym, specifically that he told McCloskey that Bouchey had alluded to assassinations. “McCloskey’s imagination went wild,” Livingston said. That grumble aside, Livingston was concerned about the hidden gay network, which he even suggested to Woodward could possibly be tied to the office of Sen. Jesse Helms, the viciously anti-gay North Carolina Republican and conservative ally of the Reagan campaign. Livingston told Woodward it would take “months to do this story right” but he hoped the Post would pursue it because “I don’t want to see the world run by a bunch of weirdos.” While Livingston allowed for the possibility that what he took as a sexual advance on the part of Bouchey might have been a mere drunken misunderstanding, “I would never base a story on just what happened to me. If you guys ever prove it, it will be world-shaking.”