Whether you’ve just started your scientific journey at the University of Manchester, or you’ve spent so much time in Simon’s Benugos that you know their whole menu by heart, you should know Manchester’s rich scientific history. Here’s just some of The Mancunion’s Science and Technology Section’s biggest scientific inspirations.

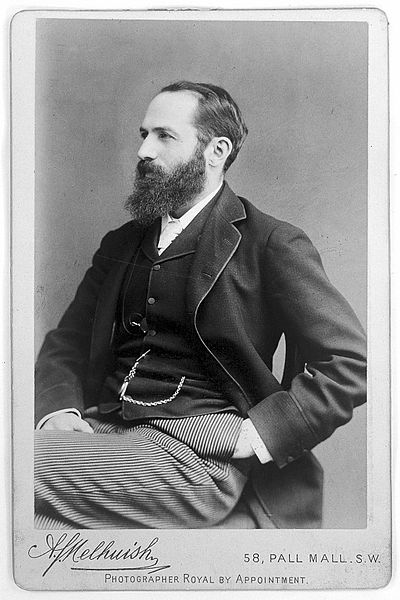

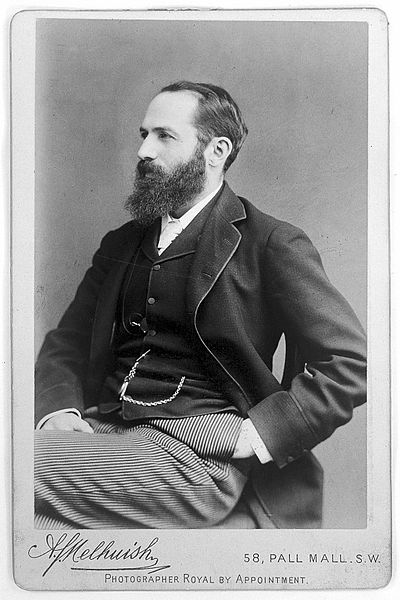

Arthur Schuster (1851-1934)

Sir Friedrich Schuster is a real inspiration for those of us foreigners who come to university seeking an opportunity. In 1900 our well-known physics department, for which he had fought and designed, was officially opened. However, as the son of German immigrants, he struggled to be recognised in the prejudiced British society of World War I. Schuster suffered from the uninformed attacks to which all others in similar circumstances were subject to at the time. By 1915 Schuster had practically stopped publishing as a consequence.

It is therefore even more important today to thank him for laying the foundations of the place where we study.

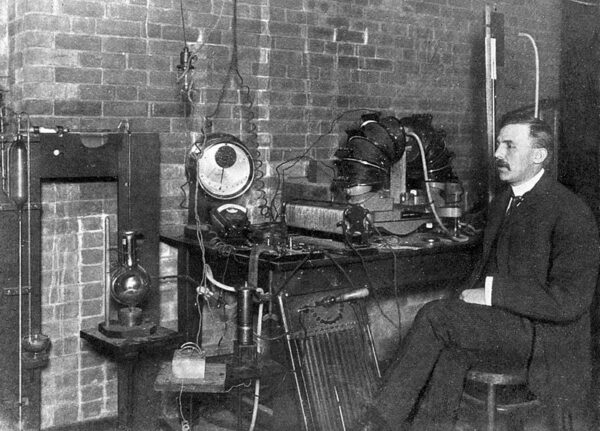

Emma Hattersley: Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937)

I obtained my place at university by going off on a 5 minute tangent on my love for Ernest Rutherford during an interview that was ostensibly about my physics ability. Fortunately, my interviewer shared my passion and didn’t kick me out for going off topic!

Born in rural New Zealand, Rutherford may have seemed an unlikely scientist, with Bill Bryson stating in his book ‘A Short History of Nearly Everything‘,

“Growing up in a remote part of a remote country, he was about as far from the mainstream of science as it was possible to be.”

After winning a scholarship that took him to Cambridge, Rutherford moved to Montreal, where he carried out the work that would later win him the Nobel Prize. The prize was awarded for his groundbreaking discovery that half of a sample of a radioactive element will always take the same amount of time to decay. Rutherford’s Nobel was granted for Chemistry, despite his most famous quote stating that “in science there is only physics; all the rest is stamp collecting.”

He made his winning discovery by carrying out tedious work that would normally have been given to more junior researchers. Such as counting alpha particle scintillations on a screen for hours and hours.

However, Rutherford is widely considered to have carried out his best research post his Nobel Prize, after he moved to Manchester. It was between 1909-1913, that he carried out his famous scattering experiment. This led to his conceptualisation of the nuclear atom. He was assisted in this task by Marsden, who was a 20-year-old undergraduate student at the time – the primary reason why I already feel washed up aged 22!

Alongside the work of Neils Bohr, Rutherford’s research brought us far closer to our modern understanding of the structure of the atom. In 1917, he carried out the first artificial nuclear reaction, cementing Manchester as the ‘birthplace of nuclear physics’.

However, it is not his scientific achievements that inspire me most, but his tenacity. He was not considered particularly gifted at maths. In fact, he was sometimes so lost in equations that he would give up in lectures and tell the students to ‘work it out for themselves’. His colleague, James Chadwick, stated that Rutherford wasn’t especially talented but simply possessed a determined and open mind.

Like Rutherford, I wouldn’t consider myself a ‘natural’ mathematician or physicist. For this reason, he remains a huge motivation for pursuing my degree. STEM is hard! It’s hard for everyone, and it might be harder for some than others. That doesn’t mean it’s not worth pursuing.

(A large amount of this information came from Bill Bryson’s book ‘A Short History of Nearly Everything’, which I highly recommend borrowing from the University Library).

Anna van der Zwaluw: Kathleen Drew-Baker (1901-1957)

Another favourite Manchester-based scientist of mine is Kathleen Drew-Baker (1901 – 1957). Although not so well-known here, she is celebrated as the ‘Mother of the Sea’ in Japan for her industry-saving findings. Without Kathleen Drew-Baker, many of us would never have experienced highly popular and delicious Japanese sushi dishes.

Kathleen studied for both her undergraduate degree and PhD at UoM, before working as a lecturer and researcher in botany at the university from 1922 until the end of her life.

Perhaps surprisingly, this Mancunian’s work was the saviour of the Japanese sushi industry. Her study included the life cycle of the red alga Porphyra umbilivalis – better known as nori seaweed used in sushi.

Nori’s reproductive life cycle has 2 phases; haploid and diploid. The haploid phase is macroscopic and recognisable as harvestable seaweed. The diploid stage, she discovered, is instead microscopic so was previously thought to be a different algal species.

Before her findings were published in Nature in 1949, nori seaweed suffered unpredictable harvests and the industry had almost ceased. Afterwards, the newfound knowledge allowed growers to develop techniques to artificially seed the crop. This significantly increased commercial production of nori, which saved this food’s industry.

In Japan, the so-called ‘Mother of the Sea’ has a dedicated shrine and is celebrated annually in the city of Uto in the eponymous Drew festival.

Matilda Leonard: Alan Turing (1912-1954)

I’m very keen to enter the world of technology after I graduate. For this reason, I am incredibly influenced by the work of computer scientist, Alan Turing. Turing lived in Manchester following his work breaking the Enigma machine during the Second World War.

He was prolific in his work, going far beyond cryptanalysis and delving into fields such as philosophy and biology. Many of his contributions to the field are still relevant today – such as the Turing Test.

Turing is also remembered for his struggle to live as an out gay man at a time when gross indecency laws existed.

Lauren Manning-Brenda Milner (1918-Present)

My favourite Mancunion scientist is Brenda Milner, a pioneering Neuroscientist born in Manchester. Milner provided vital insights into the inner workings of the human brain. Particularly how different regions of the brain interact and contribute to learning, memory and language. Her research focused on the effects of brain lesions on cognitive function. At 104 years old, Milner is still passionate in her research.

These scientists are just a small selection of the many world-changing researchers who have called Manchester home. As a section, we encourage everyone to take an interest in the history of our university, whether scientist or not. If you want to find out more, why not start by researching the scientist your lecture building is named after?