The Magician Colm Tóibín Viking, €19.99

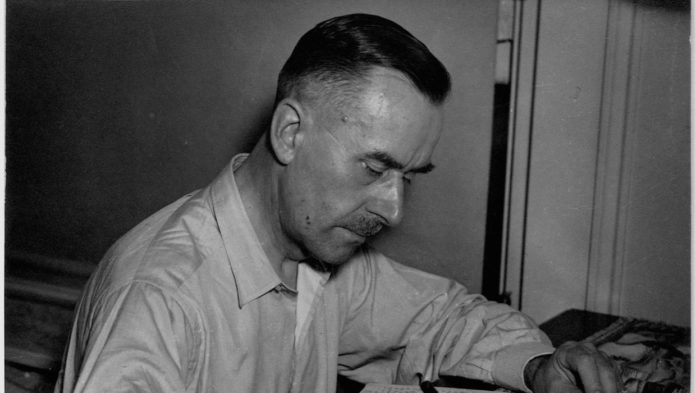

In 2008 Colm Tóibín published, in the London Review of Books (LRB), an essay on Thomas Mann and his family. The Manns – honoured, execrated, and gossiped about prodigiously during Thomas’s lifetime – called forth Tóibín’s great gifts as a literary portraitist.

Thomas Mann was, Tóibín wrote, “an immensely complex figure, conservative in his manners and ambiguous in his politics… He could have been a senator and businessman like his father had it not been for something rich and almost hidden in his nature that set him apart.”

Here, perhaps, we can glimpse the tension that may have suggested Mann to Tóibín as the potential subject for a novel. Tóibín has, of course, written before about a writer with “something rich and almost hidden in his nature” in The Master, his extraordinary 2004 novel about Henry James.

In fact, the theme of the hidden, or half-hidden, inner life and its tensions is central to almost all of Tóibín’s fiction, from The South (1990) to Nora Webster (2014). In this sense, Mann makes an obvious candidate for inclusion in Tóibín’s canon of novels about the collision of inner and outer worlds.

Like The Master, The Magician recreates the life of a great novelist who was, as Tóibín himself put it in that LRB essay, “gay most of the time”.

The “something rich and almost hidden” that marked both James’s life and Mann’s isn’t, I think, merely homosexuality, but rather homosexuality in combination with something else, to wit, the necessary furtiveness of the artist, who perforce lives two lives: one public and usually staid, the other private and almost always scourged by obsession.

Mann’s obsessions, revealed in his posthumously published diaries, tended to revolve around beautiful young men. The two major biographies of Mann in English – Ronald Hayman’s (1995) and Donald Prater’s (1995) – characterise Mann as at least partly bisexual.

Clive James summed up the “nagging question” of Mann’s sex life when he remarked that: “The quickest answer is that Thomas Mann, the solid paterfamilias, also led a fantasy life cast with handsome young men, most of them barely glimpsed in reality: a smile from a waiter could get him started on a novel.”

A divided life. In Tóibín’s telling, Mann consummates several affairs with young men in his youth. It may have happened thus. We don’t know for sure.

What we do know is that after his marriage to Katia Pringsheim in 1905 (she was wealthy and Jewish, as the Nazis did not fail to notice), Mann’s homosexual desires seem to have found expression only in his diaries and in his fiction.

He believed that publishing Death in Venice (1912), in which the lauded writer Aschenbach pines for the beautiful Polish boy Tadzio, was a risk.

Tóibín’s Mann, planning the novella, reflects that Aschenbach’s desire “could never be socialised or domesticated or made acceptable to the world”.

But contemporary reviewers understood Death in Venice as a meditation on decadence, Mann’s perennial theme.

Gay readers, of course, got the point before everyone else did. Like The Master, The Magician restores or completes our understanding of a great gay writer who could speak about his sexuality only indirectly: as symbol, as coded theme.

“Some things ran in the family,” Tóibín notes in his LRB essay. “Homosexuality, for instance.” Thomas and Katia had six children. Erika, the eldest, was gay; so was her younger brother, Klaus. They were also both writers, as was Thomas’s brother Heinrich, and another son, Golo, who was also gay.

Erika and Klaus thrived during the Weimar Republic. They were open about their sexualities in a way Thomas never could be. They also understood what Hitler represented long before Thomas did (as did Heinrich, who foresaw, as early as 1936, that the Jews of Europe would be “systematically annihilated”).

In The Magician, Thomas ignores history for as long as he possibly can. We watch as the stolid bourgeois life that has grown up around his dreamily evasive self collides, at last, with history, and with all that history entails: upheaval, exile, loss.

Line by line, Tóibín’s prose is simple. He is interested in creating, by the remorselessly patient accumulation of small actions, a fully rounded portrait.

Although there is something Mann-like about this method (as Mann himself declared, “only the exhaustive is truly interesting”), The Magician is not an especially Mann-like novel.

Where Mann was ponderous, Tóibín moves swiftly. Where Mann was essayistic, Tóibín prefers action – and in his novels, thinking, too, always feels like action.

Alongside The Master, The Magician stands as one of the richest and most perceptive novels ever written about the inner life of an artist.

Colm Tóibín has already written several truly extraordinary novels. The Magician may be the very best of them.

Kevin Power’s novel ‘White City’ is published by Scribner UK. Colm Tóibín will be in conversation with Kevin Power at the Civic, Dublin on October 17 at 6pm; civictheatre.ie