A specter is haunting America — the specter of sexual degeneracy.

Across the country, Republican state legislators are proposing bills to prohibit discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity in classrooms, purportedly to “protect” students from the perverted designs of predatory gay teachers. Prominent right-wing activists bandy about groomer as a term of opprobrium, accusing their political adversaries of trying to sexually exploit children while invoking hoary stereotypes of gay men being pedophiles. According to PEN America, a third of the books banned in public schools over the past academic year contain LGBTQ+ characters and themes. And in a troubling sign that a movement once confined to the fringes of American politics may be shaping its contours for years to come, some 30 candidates pledging fealty to QAnon, the far-right conspiracy theory envisioning a ring of cannibalistic child-sex traffickers at the heart of the American republic, are running for Congress.

Sensing political opportunity, some Republicans in Washington have exploited the passions brewing in the provinces. During last month’s confirmation hearings for Ketanji Brown Jackson, Senators Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley attempted to outdo each other in flinging accusations that the newest addition to the Supreme Court had betrayed a soft spot for child-sex predators during her tenure as a federal district court judge. Outgoing representative Madison Cawthorn raised eyebrows with his tales of “the sexual perversion” — specifically, cocaine-fueled orgies — “that goes on in Washington.” Responding to news of an infant-formula shortage, Elise Stefanik, the third-ranking House Republican, blamed “pedo grifters.”

Moral panics are nothing new in America. “We ought to learn by our mistakes,” President Harry Truman bitterly complained in 1950 as Senator Joseph McCarthy accused him and his administration of knowingly harboring communist subversives. “We’ve repeated this sort of hysteria over and over in our history,” Truman continued, reeling off a series of dates referring to the Salem witch trials, the Alien and Sedition Acts, an Anti-Masonic Party presidential campaign, the cresting of the anti-Catholic Know Nothing movement, the founding of the Ku Klux Klan, and the first Red Scare.

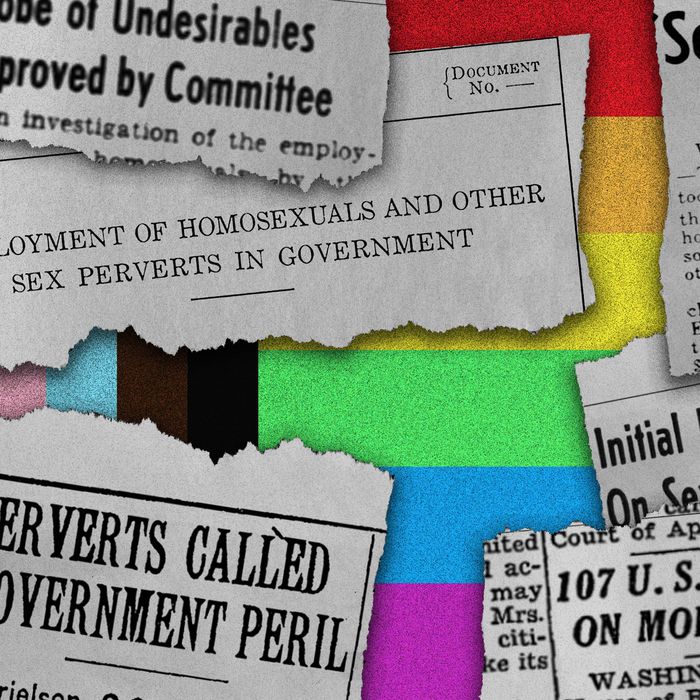

While McCarthyism would exhaust itself several years before the death of its namesake in 1957, a concurrent mass frenzy, chillingly resonant with the present-day fixation over sexual degenerates atop the commanding heights of American politics, would continue for decades. In December 1950, just a few weeks after Truman issued his gripe about the perennial susceptibility of his countrymen to moral panics, a Senate investigative subcommittee released the bipartisan report “Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government.” Commissioned in response to the shocking revelation, uttered in passing by an undersecretary of State at a congressional hearing earlier that year, that the State Department had dismissed 91 employees on the grounds of homosexuality, the report stated, “One homosexual can pollute a Government office.”

During the 1952 election that would see them achieve control over both houses of Congress and the White House for the first time since the Great Depression, Republicans placed the problem of gays in the State Department — or, as McCarthy’s colleague Everett Dirksen colorfully called them, “the lavender lads” — at the front and center of their campaign. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover disseminated the rumor that the Democratic presidential nominee, divorced former diplomat Adlai Stevenson, was one such violet-hued fellow. (That Hoover himself was the subject of similar whisperings because of his conspicuous bachelorhood and hobby of collecting antiques — a pursuit commonly associated with gay men at the time — in no way inhibited him from destroying the lives and careers of countless gay people over the course of his nearly half-century career as the most powerful man in American law enforcement.) About three months after taking office, President Dwight Eisenhower fulfilled his party’s pledge to “clean up the mess in Washington” by signing Executive Order 10450, prohibiting those guilty of “sexual perversion” — gays and lesbians — from working for the federal government or federal contractors. Not until 1975 was the gay ban in the civil service lifted, and it would take another two decades for President Bill Clinton to overturn the prohibition on gay people receiving security clearances.

As the long tail of the “Lavender Scare” demonstrates, and what the current spate of bills stigmatizing gay people as sexual predators lamentably still shows, fear of homosexuality has played a large, yet largely unappreciated, role in American politics and society. It has impacted not just gay people but the country itself, poisoning perceptions of reality and dividing us unnecessarily. Thousands of qualified people lost their jobs, and untold numbers more refrained from entering public service because of the irrational terror homosexuality once inspired in the hearts of most Americans.

Central to this fear has been the sense that gay people, by virtue of the secrecy once intrinsic to their existence, operate through subterfuge. (At the signing ceremony for the Parental Rights in Education law, dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law by critics, Florida governor Ron DeSantis declared that the measure’s opponents “support sexualizing kids in kindergarten” and “camouflage their true intentions.”) The fear underwent a dramatic change during World War II, when the concept of national security became a paramount concern and the federal government began developing a bureaucracy for the management of confidential information. If, prior to America’s rise as a global superpower, the conventional view of homosexuality held it to be immoral and a mental illness, by the time the Cold War began, it was elevated to a national-security threat, with gays allegedly more vulnerable to blackmail and therefore potentially enemies of the state. Sexual and political nonconformity came to be conflated, and “sexual deviants” assumed a place in the American political imagination rivaled only by, and frequently intertwined with, that of communists. Indeed, the standing of the homosexual was worse. A communist could leave the party, repent of his evil ways, and inform on his erstwhile comrades. Medically pathologized, morally condemned, and legally proscribed, the homosexual had no such escape from his fate.

Compelled to live in secret, gay people became fodder for all manner of political agendas and social anxieties. What some now lightheartedly refer to as a “velvet mafia” operating in certain artistic fields like fashion and entertainment once had sinister connotations. Gays were accused of subverting schools, communities, even whole nations, and it’s within the context of this long and ignoble history that the present hysteria over malevolent “groomers” working surreptitiously to corrupt the country’s youth must be understood. To comprehend America’s latest moral panic, it is necessary to recognize homophobia as not only a form of prejudice like any other but as a conspiracy theory.

The American penchant for associating sexual and gender nonconformity with political malice dates at least as far back as the election of 1800. Shortly after Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams for the presidency, a pamphleteer supporting the former accused the latter of possessing a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” But the mode of conspiratorial thinking that would come to characterize much of the popular discourse around homosexuality did not take off until the early 20th century. An awesome explanatory power would be imputed to “the love that dare not speak its name” as the motive force behind the decline and fall of ancient empires, the rise of fascism, the advance of communism, and a whole host of other events and phenomena both epochal and mundane. This was a function of two trends associated with western modernity: the growing understanding of gayness as a human identity trait (rather than a mere set of sexual acts) and the rising power of the popular press. A series of high-profile cases involving gay men in the corridors of power congealed into a cultural and political archetype — one whose literary implications Norman Mailer would explore in his 1955 essay aptly entitled “The Homosexual Villain” — with far-reaching consequences across the western world.

Like many stereotypes related to sexual decadence, the origins of the gay conspiratorial mythos can be traced to Germany. In November 1906, the editor of a Berlin-based newspaper, Maximilian Harden, started publishing a fusillade of attacks against Prince Philipp Eulenburg, a friend and adviser to Germany’s last emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II. Eulenburg, Harden claimed, sat at the center of a homosexual clique exercising a malign and perverse influence over the German ruler. As evidence, Harden cited a collection of intimate letters he had obtained in which Eulenburg and his confederates address one another by a series of effeminate endearments. (Eulenburg was called “Philine,” and Wilhelm was referred to as Liebchen, or sweetheart.) According to Harden, what the late chancellor Otto von Bismarck had called a “camarilla of pederasts” surrounded the kaiser, manipulating him into a pacifist and internationalist foreign policy that would lead imperial Germany to ruin. (One of the men Harden named as part of this gay intrigue, the French ambassador to Berlin, was referred to by the chief of the city’s police department as “the king of the pederasts.”) Loyal not to king and country but rather to their own deviant kind, these men, Harden wrote, were responsible for nothing less than “a national calamity” that risked “danger to the fatherland.” In language that would come to be used against gay men decades later when they were decimated by a deadly disease, the liberal politician Friedrich Naumann referred to them as an “international infection of sin.”

Comprising a series of libel trials and military courts-martial that continued for three years, the “Eulenburg Affair” was the first gay panic of the modern era. More than 50 journalists from around the world descended upon Germany to cover the scandal, which was comparable to the 1895 trial of Oscar Wilde for the adverse cultural and political impact it had upon what was then still a nascent popular conception of the “homosexual,” a term that had been coined less than three decades earlier. Harden’s allegations were amplified by another relatively new phenomenon: the popular, scandal-hungry “yellow” press, which zealously weaponized the charges against what it portrayed as a weak and lily-livered aristocracy. In the words of one newspaper, the Eulenburg circle was the “actual carrier of this meager and unmanly policy of reconciliation … whose after-effects we still suffer from today.” Another called for the military to be “mercilessly” purged of homosexuals. Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow demanded Wilhelm eliminate “those disgusting boils” as part of a necessary “cleansing process.”

According to the historian Robert Beachy, “More than any single event or publication, the Eulenburg scandal broadcast and popularized the notion of a homosexual identity.” And it was an identity perceived as being inextricably linked with conspiracy, treason, and moral corruption. Homosexuals were confederates in what one Swiss journalist termed “a new Freemasonry” transcending national borders, covert enemies of the state who advocated cosmopolitanism and diplomacy over nationalism and martial virtue. During one of the libel trials his articles provoked, Harden complained that, because of the notoriety of the Eulenburg faction, the prevailing view of the German government in foreign courts was that “they are homosexuals … and for that reason, there is no need for political anxiety on our part.”

Much in the way QAnon has emboldened a new generation of far-right media outlets dedicated to exposing the depraved sexual peccadilloes of America’s corrupt ruling class, so did the Eulenburg affair mark a major moment in the ability of the mass media to instigate and shape populist passions. By leveraging public anger over an elite circle of “pederasts,” the German popular press exerted unprecedented influence over traditional institutions of authority such as the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the military. In 1914, five years after the furor subsided, the Berlin correspondent for the New York Times observed that “the upheaval caused by Harden’s revelations was the most stirring victory wrought in the name of public opinion which Modern Germany has yet witnessed.” Some faulted the attitudes inflamed by the scandal for the policies that plunged the Continent into war. In 1933, the year another authoritarian and militaristic political movement took power in Germany, the pioneering gay-sex researcher Magnus Hirschfeld reflected that the Eulenburg affair was “no more and no less than a victory for the tendency that ultimately issued in the events of the World War.”

Whatever the accuracy of these claims, the verdict issued by one liberal German newspaper at the time of the scandal would prove prescient: “No more insulting accusation can be made against a man than that of abnormal sexual inclination. It ruins him psychologically and socially.”

The myth of the traitorous homosexual would seemingly be reinforced through two more political scandals, both from the German-speaking world. In 1913, the intelligence service of the Austro-Hungarian Empire discovered that its own counterespionage chief, Colonel Alfred Redl, was spying for czarist Russia. Redl was given a pistol with which to commit suicide, and after his death, the regime encouraged a narrative conflating his homosexuality with his treason. Citing evidence acquired after raiding his “thickly perfumed homosexual pleasure cave,” Austro-Hungarian authorities claimed the Russians had blackmailed Redl into working for them. When Russia declared war on Austria-Hungary the following year, the story of Redl’s treason swelled into that of legend as self-serving generals blamed their battlefield defeats on the dead colonel who had disclosed their military plans. Redl’s disgrace was so notorious that his two surviving brothers changed their surnames, and in a feature about the Redl case published more than a quarter of a century after he committed suicide, the New York Daily News, then one of America’s highest-circulation newspapers, denounced him as the “Murderer of a Million Men” who had betrayed his country “so he could buy a boyfriend a car.”

The Redl affair convinced generations of western spymasters (Allen Dulles, the first civilian director of the Central Intelligence Agency, most prominent among them) that gay people were inherently susceptible to treason. According to documents uncovered in Russian government archives in the early aughts, however, Redl’s treachery was motivated by what his Vienna neighbor, Stefan Zweig, termed “the pleasures of the senses,” not the pleasures of male flesh. Like many traitors, Redl had very expensive tastes, such that recruiting him “required no effort,” in the words of an officer from the Italian intelligence service, to which Redl also sold secrets. Redl’s gayness was also apparently unknown to his Russian handler, who referred to him as “a lover of women.”

The next gay man to solidify the apparent link between political and sexual corruption was Ernst Röhm. Founder of the Nazi paramilitary Sturmabteilung — or SA, also known as the “Brownshirts” — Röhm was unapologetic about his homosexuality. Though this made him the target of left-wing attacks, with one Social Democratic newspaper publishing his intimate correspondence with other men, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was willing to overlook his brutish lieutenant’s deviation from sexual norms. After all, he said, the SA was “not an institute for the moral education of genteel young ladies, but a formation of seasoned fighters.” Soon after taking power, however, Hitler began to view the SA as a threat, and in 1934, he ordered the execution of Röhm and his top deputies in the infamous “Night of the Long Knives.” In an impassioned speech before the Reichstag, Hitler cited the trait he had quietly tolerated for years as the reason for liquidating the Röhm cabal, denouncing

within the SA a sect sharing a certain, common orientation, who formed the kernel of a conspiracy not only against the moral conceptions of a healthy Volk but also against state security. A review of promotions carried out in May led to the terrible discovery that, within certain SA groups, men were being promoted without regard to National Socialist and SA service but only because they belonged to the circle of this orientation.

The association of Nazism and gayness — burlesqued most famously in The Producers, with its prancing, nelly Hitler and Busby Berkeley–style musical number featuring “German soldiers dancing through France, played by chorus boys in very tight pants” — was one taken quite seriously at the highest reaches of the U.S. government. Just weeks after America entered the Second World War, the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the CIA, considered a proposal to draft “patriotic homosexual men,” otherwise barred from military service, for the purposes of infiltrating the Nazi high command. A few months later, the New York Post perpetrated the first outing in American politics when it named Massachusetts senator David Walsh as the patron of an all-male brothel near the Brooklyn Navy Yard heavily populated with sailors and, allegedly, Nazi spies. Commenting on the case, the newspaper columnist and radio host Walter Winchell (who in 1933 had accused Hitler of being “a homo-sexualist, or as we Broadway vulgarians say — an out and out fairy”) crowed about “swastika swishery.”

The development of the homosexual villain reached a milestone in 1948, “the year,” John Cheever observed, “everybody in the United States was worried about homosexuality.” The root cause of their worry was Alfred Kinsey’s study Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, which found that 10 percent of American men were “more or less exclusively homosexual” for a period of at least three years between the ages of 16 and 55. The report shocked America. No longer was homosexuality a rare aberration, associated with only criminals and other disreputable elements, but one to be found “in every age group, in every social level, in every conceivable occupation, in cities and on farms, and in the most remote areas of the country.” Homosexuality was a shockingly widespread if invisible threat. “If these figures are only approximately correct,” a leading psychiatrist observed, “then the ‘homosexual outlet’ is the predominant national disease, overshadowing cancer, tuberculosis, heart failure, and infantile paralysis.”

The same week Kinsey’s report sparked a nationwide opening of closet doors, a young writer named Gore Vidal published his third novel, The City and the Pillar. Its title a reference to the biblical tale of Sodom and Gomorrah, the book was the first major work of American fiction to feature a gay protagonist sympathetically. Later that month, another quasi-autobiographical novel by a precocious young gay man, Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms, made the Times best-seller list, propelled in no small part by its scandalously come-hither author photograph. “There’s a lot of queers here,” one of Vidal’s characters observes of New York City. “They seem to be everywhere now.”

That June, Congress passed and President Truman signed into law a measure providing for the indefinite commitment of “sexual psychopaths” (a vague category including habitual homosexuals) at St. Elizabeths Hospital, a mental institution. And later that year, homosexuality played a prominent if subterranean role in the nation’s first live televised congressional hearing, at which Time magazine senior editor and confessed ex-Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers told the House Un-American Activities Committee that the former high-ranking State Department official Alger Hiss had been a co-conspirator in the communist underground. Hiss and his allies began a whisper campaign alleging that Chambers, who had secretly confessed his past “homosexualism” to the FBI, was a spurned lover out for vengeance against Hiss, and the drama between the two men established in many prominent minds a link between communism, treason, and sexual deviancy.

The politician who exploited this presumed link most effectively was McCarthy, whose infamous February 9, 1950, speech to the Republican ladies of Wheeling, West Virginia, alleging a vast communist conspiracy in the State Department was followed just weeks later by the revelation that 91 gay people had been fired from working there. Of the 25,000 letters sent to McCarthy’s office in the ensuing weeks, only one of four was primarily concerned with communist infiltration; the vast majority decried “sex depravity.” McCarthy read the public mood and tailored his message accordingly. The State Department, he declared that April, was honeycombed with “Communists and queers who have sold 400 million Asiatic people into atheistic slavery and have the American people in a hypnotic trance, headed blindly toward the same precipice.” According to the Washington columnist for the New York Daily News, “the foreign policy of the United States, even before World War II, was dominated by an all-powerful, supersecret inner circle of highly educated, socially high-placed sexual misfits, in the State Department, all easy to blackmail, all susceptible to blandishments by homosexuals in foreign nations.” In its attribution of national disaster to a gay clique, the article was a direct echo of what one German paper claimed at the height of the Eulenburg scandal: “Since 1889, German policy, especially foreign policy, has been under the aegis of the unmanly, effeminate, indecisive soft-soap Eulenburg. This perverse eunuch-and-homunculus-policy without backbone, without juice and strength, has greatly reduced Germany’s prestige and influence in the world.”

The notion of a “Homintern” — a play on the Comintern, or Communist International — was devised in the late 1930s to refer to a particular set of interwar gay English literary figures. After the defection of Guy Burgess, a flamboyantly gay British diplomat, to the Soviet Union in 1951, this sly portmanteau acquired an ominous new meaning. If Redl was the archetype of the traitorous homosexual who sells his country’s secrets under threat of blackmail, Burgess became the classic subversive of the nuclear age, the sinister queer who sabotages his country by abetting its enemies. The following year, an article in the conservative magazine Human Events warned darkly about the threat that the “Homosexual International” posed to the free world. Echoing Marcel Proust’s timeless observation (and Kinsey’s scientific validation) of gayness as a phenomenon “numbering its adherents everywhere, among the people, in the army, in the church, in the prison, on the throne,” the article’s author claimed, “This conspiracy has spread all over the globe; has penetrated all classes; operates in armies and in prisons; has infiltrated into the press, the movies and the cabinets and it all but dominates the arts, literature, theater, music and TV.”

Like antisemitic conspiracy theories, which have blamed Jews for both communism and capitalism, for being both “rootless cosmopolitans” and national chauvinists, the concept of the Homintern offered its purveyors an ideologically adaptable frame for simplifying complex and disturbing events. In 1967, New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison charged a gay businessman, Clay Shaw, as the ringleader of a conspiracy to assassinate President John F. Kennedy. The murder, Garrison privately told reporters, was a “homosexual thrill-killing” perpetrated by a coterie of right-wing, anti-communist “high-status fags.” In a cover story for Confidential, a scandal magazine that pioneered the practice of outing closeted gay public figures in the early 1950s, one of Garrison’s investigators wrote, “Two shocking parallels tie the various suspected plotters together at every turn: overt homosexuality and frustrated attempts to liberate Cuba, culminating in the Bay of Pigs affair.” Though the jury took less than an hour to acquit Shaw, Oliver Stone made Garrison’s reckless prosecution the basis of his 1991 film JFK, and he reiterated the slanderous case against Shaw in his 2021 documentary JFK Revisited.

No president was more obsessed with the gay menace than Richard Nixon, a fascination that offers a window into his paranoid, conspiratorial mind. Repeatedly in conversations with his aides, fortunately preserved for posterity by his White House taping system, Nixon can be heard blaming “fags” for everything from the collapse of ancient Greece (“You know what happened to the Greeks. Homosexuality destroyed them”) to the ruining of women’s fashion (“One of the reasons that fashions have made women look so terrible is because the goddamned designers hate women”). The obsession went beyond mere locker-room talk. It was partly in hopes of finding evidence of Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg’s nonexistent secret gay life that Nixon ordered the break-in of his psychiatrist’s office, the incident that led to the unraveling of his presidency.

No less an icon of the American right than Ronald Reagan was once tarred with the brush of the homosexual conspiracy. Early into his first term as governor of California, Reagan was rocked by a scandal involving alleged homosexuality among his staff. “Because he came out of the Hollywood scene, where homosexuality was almost the norm,” Reagan’s then–communications chief Lyn Nofziger recalled, “I also feared the rumors would insinuate that he, too, was one.” As I reveal in my book Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign was nearly derailed by charges from adversaries within his own party that he was a “Manchurian candidate” being “manipulated” by a cabal of “right-wing” homosexual advisers. The allegations were taken so seriously by Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee that he ordered a team of his top reporters, including Bob Woodward, to investigate. Though the Post did uncover the presence of several closeted gay aides, the imputation that they were up to something nefarious lacked proof, and Bradlee killed the story days before Reagan was nominated. Nonetheless, the fear that Reagan would be perceived as too chummy with gays — or possibly even gay himself — helps explain why he kept silent about the AIDS epidemic for the duration of his first term.

One of the reasons the allegations of a right-wing gay cabal controlling Reagan didn’t stick is that, by 1980, political homophobia had taken on a new guise. The increasing visibility of gay people in the years after the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion, and the concomitant rise of the religious right in reaction, fundamentally altered the politics of homosexuality. Once gay people were permitted to work for the federal civil service in 1975, the charge that they were secretly conspiring to subvert the government on behalf of foreign paymasters lost its charge. Although they would still be formally barred from obtaining security clearances for another two decades, in the eyes of a wary public, gays posed less of a threat to the security of the nation than they did to the integrity of the family. Homophobia still had a conspiratorial tinge, to be sure, but the fearsome machinations of the “Homintern” were updated to that of a “homosexual agenda” whose goals (equality in marriage, military service, and the workplace) were now out in the open.

Surveying the broad sweep of American history, the recurring waves of anti-gay hysteria form a pattern, with episodes of progress and visibility provoking cultural backlash and political repression. The historian John D’Emilio has likened World War II to a national “coming-out experience” as the mass mobilization brought millions of gay people, seemingly isolated in their existence as sexual minorities, into contact with one another for the first time. This greater societal awareness of homosexuality, described in postwar American literature and given the imprimatur of science in the Kinsey Report, collided with the nuclear anxieties of the Cold War, generating a “Lavender Scare” whose effects would be felt for decades. Likewise, the post-Stonewall efflorescence of gay liberation contributed to the rise of the Christian right, Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign, and the revival of social conservatism more broadly. What Vanity Fair lauded as “the Gay Nineties,” an era of unprecedented gay cultural visibility and a progression from what Frank Rich had described as “the Gay Decades” of the ’70s and ’80s, was followed by a campaign to insert anti-gay discrimination into the U.S. Constitution in the form of an amendment barring same-sex marriage. Today, seven years after the Supreme Court legalized gay unions, two years after it outlawed discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, and with the first openly gay Senate-confirmed member of the Cabinet, we are witnessing but the latest sex-themed moral hysteria in a country sadly prone to them.

Also uniting these panics is their character as expressions of anti-elite populism, with homosexuality singled out as a trait supposedly prevalent among a revolutionary vanguard seeking the destruction of America’s moral foundations. It is a common habit among people lacking power to devise conspiracies that explain their lack of it. From the supporters of McCarthy to the QAnon diehards of today, the purveyors of anti-gay panic speak the language of dispossession, of anger at the bewildering changes taking place around them in a country they no longer recognize. “The paranoid style is an old and recurrent phenomenon in our public life which has been frequently linked with movements of suspicious discontent,” the historian Richard Hofstadter famously wrote in 1964. In the minds of those gripped by this complex, “America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they are determined to try to repossess it and to prevent the final destructive act of subversion.” In our time, that final destructive act is being undertaken by liberal elites who both control the levers of power and prey on America’s children and turn them gay.

For those engaged in it, the moral panic over “grooming” accomplishes what earlier iterations of the Homintern, like any conspiracy theory, did: offer soothingly simple explanations for perplexing phenomena. If the latest anti-gay hysteria could be attributed to a single statistic, it would be the one reported by Gallup last year that the percent of adults identifying as other than heterosexual has doubled over the past decade from 3.5 percent in 2012 to 7.1 percent. Much of this increase owes to the 21 percent of Gen Z that identifies as LGBTQ+. While it’s certainly possible the LGBTQ+ proportion of Americans born between 1997 and 2003 is twice that of millennials and nine times that of baby-boomers, a more likely explanation is that as societal acceptance of nonnormative sexual orientations and gender identities has increased, so has the propensity of young people to claim those orientations and identities for themselves — or at the least experiment with them.

For a loud minority of Americans, the enormous social progress won by gays and lesbians over the past 75 years — the most dramatic transformation in the status of any minority in history — is deeply unsettling, as is the increased visibility of trans people. And it is for the purpose of explaining this dramatic transformation that “groomer” discourse has proliferated. As gay people marry and serve openly in the military with no adverse consequences for the rest of society, the anti-gay movement has become increasingly desperate, to the extent that it is now ginning up hysteria about pedophile elites. During an earlier time, when gay people were forced to lurk amid the shadows like communist agents, this rhetoric was fatally effective. Today, nearly every American knows somebody who is gay. Fortunately, we are no longer living under the specter of the Homintern.

Long before armchair psychoanalysis of the American president became a national hobby, two prominent authors insinuated that the failure of the Treaty of Versailles was due to President Woodrow Wilson’s repressed homosexuality. In Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study, the former senior American diplomat William C. Bullitt and Sigmund Freud alleged that Wilson suffered from an Oedipus complex that compelled him to seek “an affectionate relationship with younger and physically smaller men, preferably blond.” Wilson, they explained, “met the leaders of the Allies not with the weapons of masculinity but with the weapons of femininity: appeals, supplications, concessions, submissions.” Published in 1966, the book caused a scandal upon its release, drawing a critical reception that The Times Literary Supplement characterized as “a practical unanimity of condemnation that has had few parallels in recent historical controversy.”

During the war, the federal government commissioned two studies by acclaimed Harvard medical doctors, both of which dwelled at length upon the supposed connections between homosexuality and Nazism. “The fact that underneath they feel themselves to be different and ostracized from normal social contacts usually makes them easy converts to a new social philosophy that does not discriminate against them,” Walter C. Langer observed of homosexuals in The Mind of Adolf Hitler. “Being among civilization’s discontents, they are always willing to take a chance on something new that holds any promise of improving their lot, even though their chances of success may be small and the risk great.”

Ribaldry linking the State Department with gay men was hardly limited to the right. In his 1949 book The Vital Center, no less a paragon of mainstream American liberalism than Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote of the State Department as a repository of “effete and conventional men who adored countesses, pushed cookies and wore handkerchiefs in their sleeves.” A 1950 New Yorker cartoon shows a job applicant pleading with an employer, “It’s true, sir, that the State Department let me go, but that was solely because of incompetence.”

“At best the elimination of homosexuals from Government agencies is only one phase of combating the homosexual invasion of American public life,” the author R.G. Waldeck wrote before offering an observation that would not be out of place in today’s debates over how sexual orientation ought to be discussed, if at all, in schools. “Another phase, more important in the long run, is the matter of public education. This should be clear to anyone who views with dismay the forbearance bordering on tenderness with which American society not only tolerates the infiltration of homosexuals everywhere but even allows them to display their perversion in public.”