The 1901 Dorland’s Medical Dictionary defined heterosexuality as an “abnormal or perverted appetite toward the opposite sex.” More than two decades later, in 1923, Merriam Webster’s dictionary similarly defined it as “morbid sexual passion for one of the opposite sex.” It wasn’t until 1934 that heterosexuality was graced with the meaning we’re familiar with today: “manifestation of sexual passion for one of the opposite sex; normal sexuality.”

Whenever I tell this to people, they respond with dramatic incredulity. That can’t be right! Well, it certainly doesn’t feel right. It feels as if heterosexuality has always “just been there.”

A few years ago, there began circulating a “man on the street” video, in which the creator asked people if they thought homosexuals were born with their sexual orientations. Responses were varied, with most saying something like, “It’s a combination of nature and nurture.” The interviewer then asked a follow-up question, which was crucial to the experiment: “When did you choose to be straight?” Most were taken back, confessing, rather sheepishly, never to have thought about it. Feeling that their prejudices had been exposed, they ended up swiftly conceding the videographer’s obvious point: gay people were born gay just like straight people were born straight.

The video’s takeaway seemed to suggest that all of our sexualities are “just there”; that we don’t need an explanation for homosexuality just as we don’t need one for heterosexuality. It seems not to have occurred to those who made the video, or the millions who shared it, that we actually need an explanation for both.

There’s been a lot of good work, both scholarly and popular, on the social construction of homosexual desire and identity. As a result, few would bat an eye when there’s talk of “the rise of the homosexual” – indeed, most of us have learned that homosexual identity did come into existence at a specific point in human history. What we’re not taught, though, is that a similar phenomenon brought heterosexuality into its existence.

There are many reasons for this educational omission, including religious bias and other types of homophobia. But the biggest reason we don’t interrogate heterosexuality’s origins is probably because it seems so, well, natural. Normal. No need to question something that’s “just there.”

But heterosexuality has not always “just been there.” And there’s no reason to imagine it will always be.

When heterosexuality was abnormal

The first rebuttal to the claim that heterosexuality was invented usually involves an appeal to reproduction: it seems obvious that different-genital intercourse has existed for as long as humans have been around – indeed, we wouldn’t have survived this long without it. But this rebuttal assumes that heterosexuality is the same thing as reproductive intercourse. It isn’t.

“Sex has no history,” writes queer theorist David Halperin at the University of Michigan, because it’s “grounded in the functioning of the body.” Sexuality, on the other hand, precisely because it’s a “cultural production,” does have a history. In other words, while sex is something that appears hardwired into most species, the naming and categorising of those acts, and those who practise those acts, is a historical phenomenon, and can and should be studied as such.

Or put another way: there have always been sexual instincts throughout the animal world (sex). But at a specific point in time, humans attached meaning to these instincts (sexuality). When humans talk about heterosexuality, we’re talking about the second thing.

Hanne Blank offers a helpful way into this discussion in her book Straight: The Surprisingly Short History of Heterosexuality with an analogy from natural history. In 2007, the International Institute for Species Exploration listed the fish Electrolux addisoni as one of the year’s “top 10 new species.” But of course, the species didn’t suddenly spring into existence 10 years ago – that’s just when it was discovered and scientifically named. As Blank concludes: “Written documentation of a particular kind, by an authority figure of a particular kind, was what turned Electrolux from a thing that just was … into a thing that was known.”

Something remarkably similar happened with heterosexuals, who, at the end of the 19th Century, went from merely being there to being known. “Prior to 1868, there were no heterosexuals,” writes Blank. Neither were there homosexuals. It hadn’t yet occurred to humans that they might be “differentiated from one another by the kinds of love or sexual desire they experienced.” Sexual behaviours, of course, were identified and catalogued, and often times, forbidden. But the emphasis was always on the act, not the agent.

So what changed? Language.

In the late 1860s, Hungarian journalist Karl Maria Kertbeny coined four terms to describe sexual experiences: heterosexual, homosexual, and two now forgotten terms to describe masturbation and bestiality; namely, monosexual and heterogenit. Kertbeny used the term “heterosexual” a decade later when he was asked to write a book chapter arguing for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. The editor, Gustav Jager, decided not to publish it, but he ended up using Kertbeny’s novel term in a book he later published in 1880.

The next time the word was published was in 1889, when Austro-German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing included the word in Psychopathia Sexualis, a catalogue of sexual disorders. But in almost 500 pages, the word “heterosexual” is used only 24 times, and isn’t even indexed. That’s because Krafft-Ebing is more interested in “contrary sexual instinct” (“perversions”) than “sexual instinct,” the latter being for him the “normal” sexual desire of humans.

“Normal” is a loaded word, of course, and it has been misused throughout history. Hierarchical ordering leading to slavery was at one time accepted as normal, as was a geocentric cosmology. It was only by questioning the foundations of the consensus view that “normal” phenomena were dethroned from their privileged positions.

For Krafft-Ebing, normal sexual desire was situated within a larger context of procreative utility, an idea that was in keeping with the dominant sexual theories of the West. In the Western world, long before sex acts were separated into the categories hetero/homo, there was a different ruling binary: procreative or non-procreative. The Bible, for instance, condemns homosexual intercourse for the same reason it condemns masturbation: because life-bearing seed is spilled in the act. While this ethic was largely taught, maintained, and enforced by the Catholic Church and later Christian offshoots, it’s important to note that the ethic comes not primarily from Jewish or Christian Scriptures, but from Stoicism.

As Catholic ethicist Margaret Farley points out, Stoics “held strong views on the power of the human will to regulate emotion and on the desirability of such regulation for the sake of inner peace”. Musonius Rufus, for example, argued in On Sexual Indulgence that individuals must protect themselves against self-indulgence, including sexual excess. To curb this sexual indulgence, notes theologian Todd Salzman, Rufus and other Stoics tried to situate it “in a larger context of human meaning” – arguing that sex could only be moral in the pursuit of procreation. Early Christian theologians took up this conjugal-reproductive ethic, and by the time of Augustine, reproductive sex was the only normal sex.

While Krafft-Ebing takes this procreative sexual ethic for granted, he does open it up in a major way. “In sexual love the real purpose of the instinct, the propagation of the species, does not enter into consciousness,” he writes.

In other words, sexual instinct contains something like a hard-wired reproductive aim – an aim that is present even if those engaged in ‘normal’ sex aren’t aware of it. Jonathan Ned Katz, in The Invention of Heterosexuality, notes the impact of Krafft-Ebing’s move. “Placing the reproductive aside in the unconscious, Krafft-Ebing created a small, obscure space in which a new pleasure norm began to grow.”

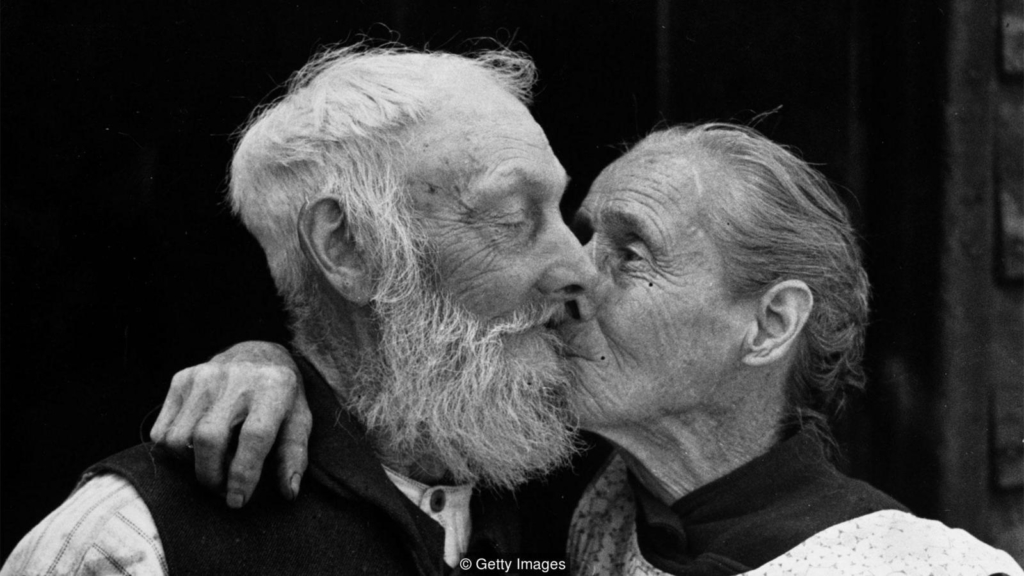

The importance of this shift – from reproductive instinct to erotic desire – can’t be overstated, as it’s crucial to modern notions of sexuality. When most people today think of heterosexuality, they might think of something like this: Billy understands from a very young age he is erotically attracted to girls. One day he focuses that erotic energy on Suzy, and he woos her. The pair fall in love, and give physical sexual expression to their erotic desire. And they live happily ever after.

Without Krafft-Ebing’s work, this narrative might not have ever become thought of as “normal.” There is no mention, however implicit, of procreation. Defining normal sexual instinct according to erotic desire was a fundamental revolution in thinking about sex. Krafft-Ebing’s work laid the groundwork for the cultural shift that happened between the 1923 definition of heterosexuality as “morbid” and its 1934 definition as “normal.”

Sex and the city

Ideas and words are often products of their time. That is certainly true of heterosexuality, which was borne out of a time when American life was becoming more regularised. As Blank argues, the invention of heterosexuality corresponds with the rise of the middle class.

In the late 19th Century, populations in European and North American cities began to explode. By 1900, for example, New York City had 3.4 million residents – 56 times its population just a century earlier. As people moved to urban centres, they brought their sexual perversions – prostitution, same-sex eroticism – with them. Or so it seemed. “By comparison to rural towns and villages,” Blank writes, “the cities seemed like hotbeds of sexual misconduct and excess.” When city populations were smaller, says Blank, it was easier to control such behaviour, just as it was easier to control when it took place in smaller, rural areas where neighbourly familiarity was a norm. Small-town gossip can be a profound motivator.

Because the increasing public awareness of these sexual practices paralleled the influx of lower classes into cities, “urban sexual misconduct was typically, if inaccurately, blamed” on the working class and poor, says Blank. It was important for an emerging middle class to differentiate itself from such excess. The bourgeois family needed a way to protect its members “from aristocratic decadence on the one side and the horrors of the teeming city on the other”. This required “systematic, reproducible, universally applicable systems for social management that could be implemented on a large scale”.

In the past, these systems could be based on religion, but “the new secular state required secular justification for its laws,” says Blank. Enter sex experts like Krafft-Ebing, who wrote in the introduction to his first edition of Psychopathia that his work was designed “to reduce [humans] to their lawful conditions.” Indeed, continues the preface, the present study “exercises a beneficent influence upon legislation and jurisprudence”.

Krafft-Ebing’s work chronicling sexual irregularity made it clear that the growing middle class could no longer treat deviation from normal (hetero) sexuality merely as sin, but as moral degeneracy – one of the worst labels a person could acquire. “Call a man a ‘cad’ and you’ve settled his social status,” wrote Williams James in 1895. “Call him a ‘degenerate’ and you’ve grouped him with the most loathsome specimens of the human race.” As Blank points out, sexual degeneracy became a yardstick to determine a person’s measure.

Degeneracy, after all, was the reverse process of social Darwinism. If procreative sex was critical to the continuous evolution of the species, deviating from that norm was a threat to the entire social fabric. Luckily, such deviation could be reversed, if it was caught early enough, thought the experts.

The formation of “sexual inversion” occurred, for Krafft-Ebing, through several stages, and was curable in the first. Through his work, writes Ralph M Leck, author of Vita Sexualis, “Krafft-Ebing sent out a clarion call against degeneracy and perversion. All civic-minded people must take their turn on the social watch tower.” And this was certainly a question of civics: most colonial personnel came from the middle class, which was large and growing.

Though some non-professionals were familiar with Krafft-Ebing’s work, it was Freud who gave the public scientific ways to think about sexuality. While it’s difficult to reduce the doctor’s theories to a few sentences, his most enduring legacy is his psychosexual theory of development, which held that children develop their own sexualities via an elaborate psychological parental dance.

For Freud, heterosexuals weren’t born this way, but made this way. As Katz points out, heterosexuality for Freud was an achievement; those who attained it successfully navigated their childhood development without being thrown off the straight and narrow.

And yet, as Katz notes, it takes an enormous imagination to frame this navigation in terms of normality:

According to Freud, the normal road to heterosexual normality is paved with the incestuous lust of boy and girl for parent of the other sex, with boy’s and girl’s desire to murder their same-sex parent-rival, and their wish to exterminate any little sibling-rivals. The road to heterosexuality is paved with blood-lusts… The invention of the heterosexual, in Freud’s vision, is a deeply disturbed production.

That such an Oedipal vision endured for so long as the explanation for normal sexuality is “one more grand irony of heterosexual history,” he says.

Still, Freud’s explanation seemed to satisfy the majority of the public, who, continuing their obsession with standardising every aspect of life, happily accepted the new science of normal. Such attitudes found further scientific justification in the work of Alfred Kinsey, whose landmark 1948 study Sexual Behavior in the Human Male sought to rate the sexuality of men on a scale of zero (exclusively heterosexual) to six (exclusively homosexual). His findings led him to conclude that a large, if not majority, “portion of the male population has at least some homosexual experience between adolescence and old age”. While Kinsey’s study did open up the categories homo/hetero to allow for a certain sexual continuum, it also “emphatically reaffirmed the idea of a sexuality divided between” the two poles, as Katz notes.

The future of heterosexuality

And those categories have lingered to this day. “No one knows exactly why heterosexuals and homosexuals ought to be different,” wrote Wendell Ricketts, author of the 1984 study Biological Research on Homosexuality. The best answer we’ve got is something of a tautology: “heterosexuals and homosexuals are considered different because they can be divided into two groups on the basis of the belief that they can be divided into two groups.”

Though the hetero/homo divide seems like an eternal, indestructible fact of nature, it simply isn’t. It’s merely one recent grammar humans have invented to talk about what sex means to us.

Heterosexuality, argues Katz, “is invented within discourse as that which is outside discourse. It’s manufactured in a particular discourse as that which is universal… as that which is outside time.” That is, it’s a construction, but it pretends it isn’t. As any French philosopher or child with a Lego set will tell you, anything that’s been constructed can be deconstructed, as well. If heterosexuality didn’t exist in the past, then it doesn’t need to exist in the future.

I was recently caught off guard by Jane Ward, author of Not Gay, who, during an interview for a piece I wrote on sexual orientation, asked me to think about the future of sexuality. “What would it mean to think about people’s capacity to cultivate their own sexual desires, in the same way we might cultivate a taste for food?” Though some might be wary of allowing for the possibility of sexual fluidity, it’s important to realise that various Born This Way arguments aren’t accepted by the most recent science. Researchers aren’t sure what “causes” homosexuality, and they certainly reject any theories that posit a simple origin, such as a “gay gene.” It’s my opinion that sexual desires, like all our desires, shift and re-orient throughout our lives, and that as they do, they often suggest to us new identities. If this is true, then Ward’s suggestion that we can cultivate sexual preferences seems fitting. (For more of the scientific evidence behind this argument, read BBC Future’s ‘I am gay – but I wasn’t born this way’.)

Beyond Ward’s question is a subtle challenge: If we’re uncomfortable with considering whether and how much power we have over our sexualities, why might that be? Similarly, why might we be uncomfortable with challenging the belief that homosexuality, and by extension heterosexuality, are eternal truths of nature?

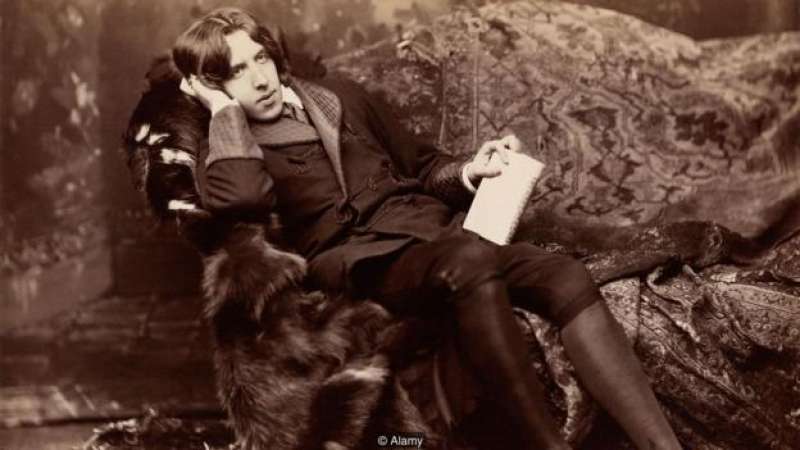

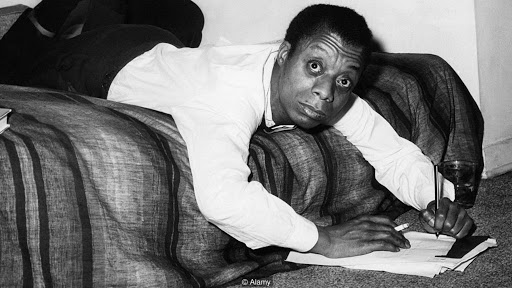

In an interview with the journalist Richard Goldstein, the novelist and playwright James Baldwin admitted to having good and bad fantasies of the future. One of the good ones was that “No one will have to call themselves gay,” a term Baldwin admits to having no patience for. “It answers a false argument, a false accusation.”

Which is what?

“Which is that you have no right to be here, that you have to prove your right to be here. I’m saying I have nothing to prove. The world also belongs to me.”

Once upon a time, heterosexuality was necessary because modern humans needed to prove who they were and why they were, and they needed to defend their right to be where they were. As time wears on, though, that label seems to actually limit the myriad ways we humans understand our desires and loves and fears. Perhaps that is one reason a recent UK poll found that fewer than half of those aged 18-24 identify as “100% heterosexual.” That isn’t to suggest a majority of those young respondents regularly practise bisexuality or homosexuality; rather it shows that they don’t seem to have the same need for the word “heterosexual” as their 20th-Century forebears.

Debates about sexual orientation have tended to focus on a badly defined concept of “nature.” Because different sex intercourse generally results in the propagation of the species, we award it a special moral status. But “nature” doesn’t reveal to us our moral obligations – we are responsible for determining those, even when we aren’t aware we’re doing so. To leap from an observation of how nature is to a prescription of nature ought to be is, as philosopher David Hume noted, to commit a logical fallacy.

Why judge what is natural and ethical to a human being by his or her animal nature? Many of the things human beings value, such as medicine and art, are egregiously unnatural. At the same time, humans detest many things that actually are eminently natural, like disease and death. If we consider some naturally occurring phenomena ethical and others unethical, that means our minds (the things looking) are determining what to make of nature (the things being looked at). Nature doesn’t exist somewhere “out there,” independently of us – we’re always already interpreting it from the inside.

Until this point in our Earth’s history, the human species has been furthered by different-sex reproductive intercourse. About a century ago, we attached specific meanings to this kind of intercourse, partly because we wanted to encourage it. But our world is very different now than what it was. Technologies like preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and in vitro fertilisation (IVF) are only improving. In 2013, more than 63,000 babies were conceived via IVF. In fact, more than five million children have been born through assisted reproductive technologies. Granted, this number still keeps such reproduction in the slim minority, but all technological advances start out with the numbers against them.

Socially, too, heterosexuality is losing its “high ground,” as it were. If there was a time when homosexual indiscretions were the scandals du jour, we’ve since moved on to another world, one riddled with the heterosexual affairs of politicians and celebrities, complete with pictures, text messages, and more than a few video tapes. Popular culture is replete with images of dysfunctional straight relationships and marriages. Further, between 1960 and 1980, Katz notes, the divorce rate rose 90%. And while it’s dropped considerably over the past three decades, it hasn’t recovered so much that anyone can claim “relationship instability” is something exclusive to homosexuality, as Katz shrewdly notes.

The line between heterosexuality and homosexuality isn’t just blurry, as some take Kinsey’s research to imply – it’s an invention, a myth, and an outdated one. Men and women will continue to have different-genital sex with each other until the human species is no more. But heterosexuality – as a social marker, as a way of life, as an identity – may well die out long before then.