Smithsonian Voices National Museum of American History

The History of Getting the Gay Out

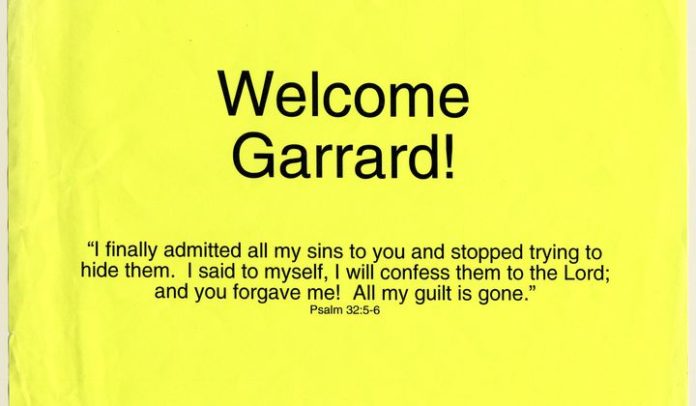

It is dangerous to be different, and certain kinds of difference are especially risky. Race, disability, and sexuality are among the many ways people are socially marked that can make them vulnerable. The museum recently collected materials to document gay-conversion therapy (also called “reparative therapy”)—and these objects allow curators like myself to explore how real people experience these risks. With the help of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., Garrard Conley gave us the workbook he used in 2004 at a now defunct religious gay-conversion camp in Tennessee, called “Love in Action.” We also received materials from John Smid, who was camp director. Conley’s memoir of his time there, Boy Erased, chronicles how the camp’s conversion therapy followed the idea that being gay was an addiction that could be treated with methods similar to those for abating drug, alcohol, gambling, and other addictions. While there, Conley spiraled into depression and suicidal thoughts. Conley eventually escaped. Smid eventually left Love in Action and married a man.

In the United States, responses to gay, homosexual, queer, lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, and gender non-conforming identities have fluctuated from “Yes!” and “Who cares?” to legal sanctions, medical treatment, violence, and murder. When and why being LGBTQ+ became something that needed “fixing” has a checkered history. In the late 1800s attempts intensified to prevent, cure, or punish erotic and sexual desires that were not female-male. Non-conforming behavior underwent a dramatic shift as the word “homosexuality” (coined in 1869)—a counter to heterosexuality—became popular. The main objections to non-binary orientations were based in physiology and psychology, religion, and beliefs about morality and politics.

When non-conforming identities were considered a medical disease, psychiatrists used medical treatments, such as electroconvulsive shock, lobotomy, drugs, and psychoanalysis to cure or prevent “deviancy.” Psychologists in the 1960s and 1970s described being LGBTQ+ as an attachment disorder—that people were attached to inappropriate erotic or sexual desires. They believed that using aversions (such as electrical shock stimuli) could modify behavior and lead to heterosexuality and “cure.” It did not work.

Homosexuality was considered a psychiatric disorder until 1973, when it was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). It returned to later editions under other names, downgraded to maladjustment. After science got out of the bedroom, the law removed itself as well in 2003 with the Lawrence v. Texas Supreme Court decision that invalidated sodomy laws. For the last 20 years or so, conversion therapy has been discredited scientifically and is no longer medically approved as effective or appropriate.

Just as religious conviction and faith are part of some addiction programs, religious beliefs about sexuality and gender form the only remaining justifications for “gay conversion.” Religion justifies conversion, frames the therapy, and is called upon as strength for an individual’s “cure.” Although outlawed in several states, religion-based seminars, camps, and individual sessions continue. Attempts to “save” a person through reforming or curing a desire deemed sinful often have damaging effects. For example, bullying of and discrimination against LGBTQ+ youth contribute to high rates of suicide, addiction, and depression.

Being different can be dangerous.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History’s blog on November 15, 2018. Read the original version here.