It was a warm June day in Fort Worth when a defiant woman took the stage outside the 1998 Texas Republican Convention, facing signs that read “In Texas, we like steers but not queers” and “We can’t tolerate these filthy sodomites.” Several dozen openly gay Republican delegates and alternates gathered outside the convention to protest their lack of inclusion in the proceedings. Opposite them, anti-gay groups attempted to shout them down.

The woman wasn’t a Republican, but she cared about inclusion. She called out a sign telling the gay delegates to go back to San Francisco. She wore a short bob haircut, large aviator sunglasses, and a long blue blazer that she whipped about as she spoke with passion.

“I want you to know, we are not from San Francisco,” she said. “I was born right here in Fort Worth, Texas.” The crowd erupted in applause.

How I came to a video of that speech and wound up befriending an icon of the Dallas LGBTQ community is a story with a few twists. Like all great treasure hunts, it began with a map.

One day last year, in an attempt to avoid traffic, I zoomed in on a map on my phone. For a reason only the Google algorithm knows, I saw a neighborhood name I’d never heard of: Loryland. Near the intersection of Royal and Marsh lanes, it was an area west of Preston Hollow. Call it Northwest Dallas. Poking around online, I found a few people cheering for the digital recognition of what had long been an unofficial moniker for the area. It was named for a real estate broker who had sold homes in the area for decades: Lory Masters.

I went. Masters had sold her first house in the neighborhood and owned a real estate company for 35 years. She threw massive Loryland parties (complete with branded t-shirts) at her house and was an influential organizer and fundraiser in the LGBTQ community. She played professional football for the Dallas Bluebonnets, started a lesbian motorcycle club, and had an archive dedicated to her records at UNT.

I had to meet this woman. I figured she had to be around 70, but her realty company had closed years ago. I thought the chances of connecting with her were slim, but I found a Twitter account that seemed to be active in Dallas with her name. I messaged her, but she didn’t know how Loryland had ended up on Google Maps, so I went straight to the source. Sadly, Google didn’t have a specific explanation of how Loryland had ended up on their map but said, in general, neighborhood names come from public sources, users’ feedback, and third-party neighborhood name providers.

Eventually, I found myself driving to that UNT archive with Masters, touring Loryland, meeting her neighbors, and bringing home feathers for my young sons from Lady Boo, her pet macaw. In my first conversations with her, I discovered what so many already knew. Lory Masters never met a stranger. And it made sense that her reach and influence were so vast that Google had no choice but to label the neighborhood what everyone was already calling it.

The people put Loryland on the map.

The Sculpture In Her Honor

The Interfaith Peace Chapel exudes an otherworldliness that is both unsettling and comforting. Architect Philip Johnson designed it to avoid parallel lines and right angles. The interior white walls and open spaces balance a cavernous openness with warmth.

The small chapel and the main Cathedral of Hope, which sits behind Johnson’s massive bell wall, wouldn’t exist without Masters, who co-led a $40 million capital campaign for the church in the late ’90s. She chaired the effort with her best friend John Thomas, the founder of the AIDS Resource Center and an original member of the Turtle Creek Chorale, with whom he sang for 19 years; the bell wall at the cathedral is named for him. The two traveled the country, raising money for what is now the largest predominantly gay and lesbian church in the world.

Masters cut her organizational teeth with the Business and Professional Women’s Association, where she became a parliamentarian and learned how to run a board meeting. The Dallas chapter of the organization was founded in 1919 to connect professional women, and Masters was able to develop friendships with leaders like Judge Sarah T. Hughes along her way to becoming president of the organization in 1980. Over the years, she also sat on the boards for the Black Tie Dinner, The Women’s Chorus of Dallas, and the Oak Lawn Counseling Center.

Courtesy UNT Libraries Special Collections

Cathedral of Hope; Lesley Busby

“She is the person who you go to when you need fundraising, when you need somebody to serve on a board, when you need somebody to do something for an event,” says De’An Olson Roper, a social work professor at UTA who met Masters as a young activist. “She is always willing to give her money and herself.”

Outside the Interfaith Peace Chapel and adjacent to a garden and shade trees, there stands a red sculpture more than 10 feet tall. The Nic Noblique piece was commissioned to honor Masters’ 70th birthday and was given to her to recognize her work in leading the fundraising for the cathedral.

“She was an icon,” says Steve Atkinson, who worked at Masters’ realty company and helped organize the effort to commission the statue. “There were quite a few men and women from her generation who were building and founding organizations, making them big and strong. That all led to the powerful LGBTQ community that we have in Dallas. People that didn’t know Dallas would not expect that we would have that, even today, and she was a big part of it.”

The metal sculpture twists up in an arching rotation, like a red ribbon that has been twirled up in the air and then allowed to fall. It’s so close to the exterior of the building that it is practically part of the design.

“I swear we must have all been smoking dope,” Masters says, describing the sculpture. “I don’t know what the hell got them to put up a monument. Oh, but it’s beautiful.”

The Motorcycle Club

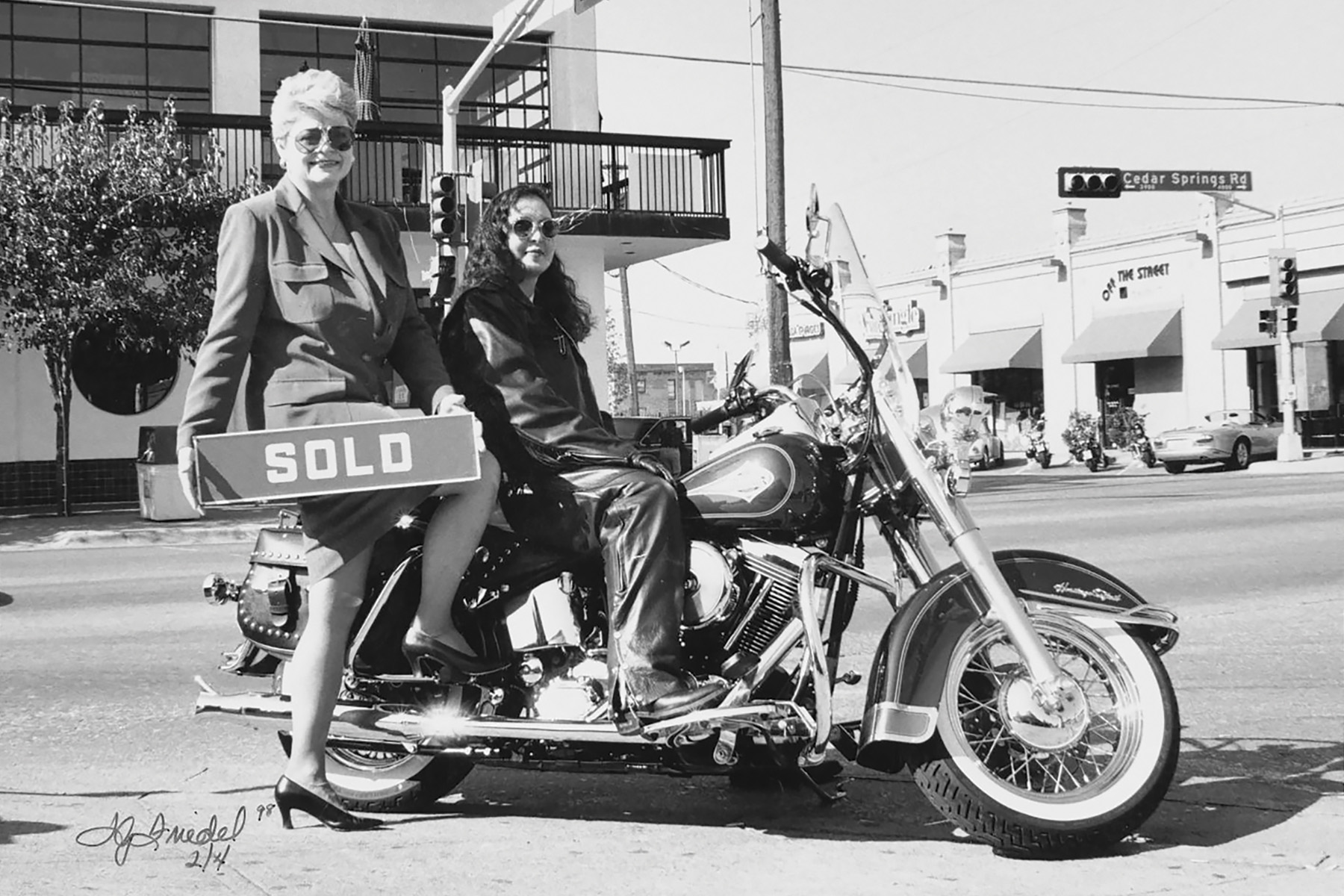

There probably aren’t too many motorcycle clubs that use parliamentary procedure in their meetings, but there aren’t too many parliamentarians who enjoy cruising on the weekends in a chromed-out Harley-Davidson 250 Sprint.

When a friend of Masters’ and a local judge she declines to name began taking weekend motorcycle rides in the early ’70s, Masters decided to join them. The group slowly grew, using a phone tree to spread the word and make plans for weekend rides. But when the crew became too large, Masters knew they needed to get serious. So she formed a lesbian motorcycle club.

She created a 501(c)(3) for the group in 1976, the first LGBTQ motorcycle club nonprofit in the South. She wrote the bylaws and the mission statement, kept minutes, and ran the club business with the tidy organization of a board meeting. The club operated for more than 30 years.

She named the group The Flying W, inspired by a moment in the 1971 Oscar-nominated motorcycle racing documentary On Any Sunday. In one scene, a racer flies over his handlebars, arms extended to brace his fall. Just before he hits the ground, his arms and helmet form a W.

In addition to weekend rides, campouts, and road trips to ski in New Mexico, the group would travel around Texas and Louisiana, putting on lesbian drag shows that raised funds for other LGBTQ organizations. Masters emceed the events.

She describes her Harley years this way: “I was an exhibitionist with hair down the back of my—you know. Oh, God, I had fun.”

The Brief Football Career

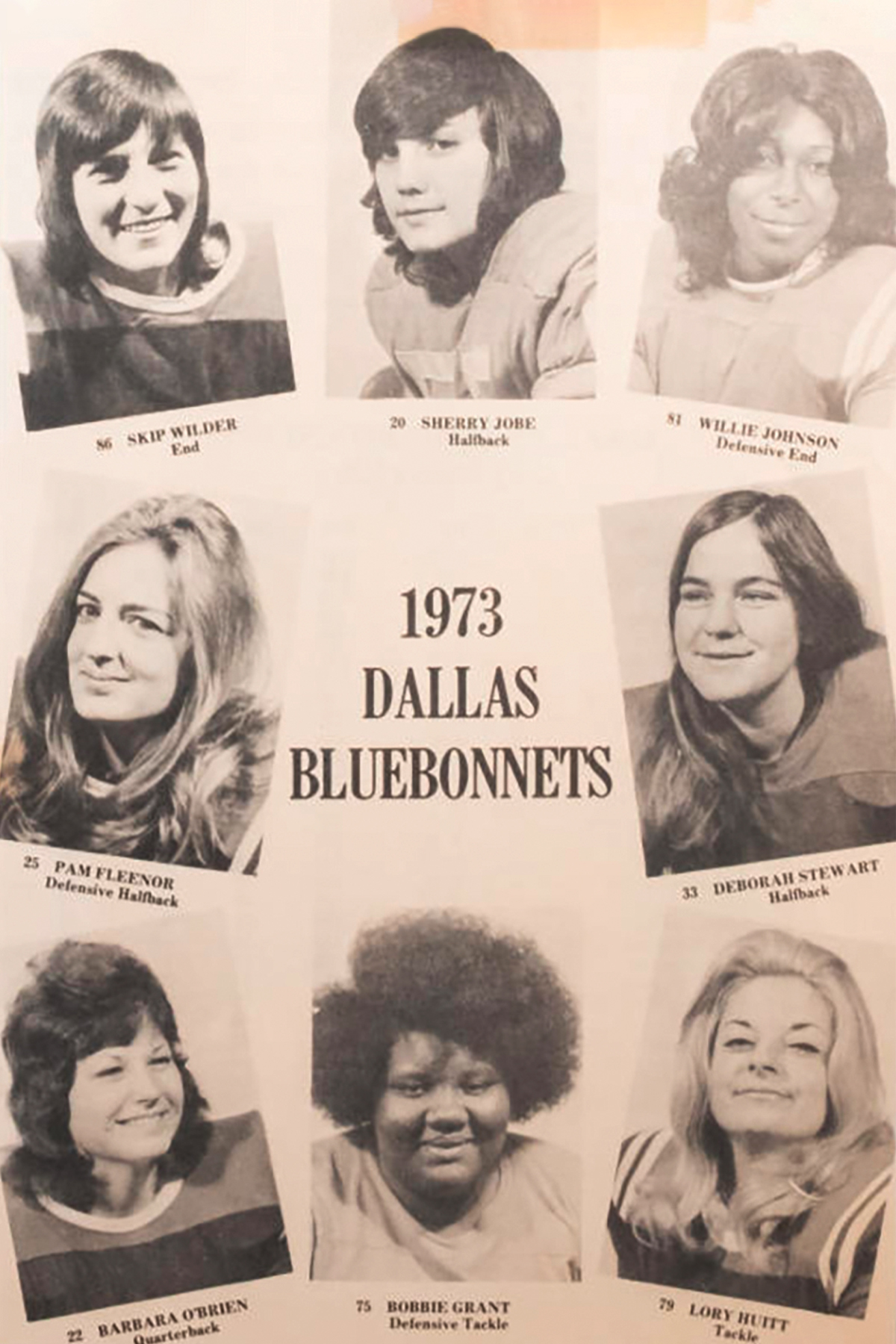

Until she took the field for the Dallas Bluebonnets, Masters had never played football before. It was the team’s inaugural season. She lasted a year; the team lasted two.

A friend named Pam Fleenor, who played what was termed defensive halfback, reached out to Masters about playing. Masters wondered why Fleenor was calling her; she didn’t even know the rules of football. But Masters is a joiner, so she suited up.

A 1973 promotional poster shows Masters (then Lory Huitt) squinting at the camera with a sly smile, her long blond hair resting on her shoulder pads. She is listed as a tackle. A contemporaneous article describes the team’s arrival: “Look out Cowboys, ‘Bluebonnets’ prove football [is] for chicks, too.”

The Bluebonnets were part of the National Women’s Football League and played at Texas Stadium. Masters remembers the first game vividly. The Bluebonnets lined up against the Toledo Troopers, who would go on to dominate the league. A Trooper flattened Masters early in the game, and she looked to the team’s enforcer, defensive tackle Bobbie Grant, for help.

“Bobbie, she hurt me,” Masters pleaded.

“The next play,” she tells me, “Bobbie got her.”

Masters tore a ligament in that game but didn’t want to stop playing. She asked the team medic to deaden her foot and tape her up so she could get back in.

“I got pretty damn hurt several times,” she says.

Masters loved the camaraderie of the Bluebonnets. In a North Dallas cafe 50 years later, she rattles off 10 names of her teammates from that season, as if she had just finished practice. “A lot of these people are still here,” she says.

The Giving Spirit

On a road trip with Masters to visit the archive devoted to her personal collection of LGBTQ history in Dallas, she tells me about her two current houseguests. These aren’t family members or anyone she has lived with for a long time but two friends who needed a place to stay. One is an older woman dealing with mental health issues. Masters took her in, no questions asked. She helps her grocery shop, makes sure she gets her meds, and tries to provide social interaction. She lives in one of Masters’ guest bedrooms in her midcentury ranch in the Disney Streets, the beating heart of Loryland. The other houseguest is a young man who travels a lot for work and needs a place to stay sporadically.

Over the years, as a matriarch of the Dallas LGBTQ community, Masters has been generous with her time and money. But she also knows what it is like to need support. She has been sober for nearly 40 years and is always ready to offer whatever she can to those in recovery.

Courtesy UNT Libraries Special Collections

Courtesy UNT Libraries Special Collections

“I can remember several people living with us for a couple of months at a time until they got back on their feet,” says Cindy Huitt, Masters’ daughter. “If there was somebody in need, she never met a stranger.”

“She makes you feel like you’re the only one in the room, and that you’re the most important thing to her,” says Olson Roper, the UTA professor. “She raises millions of dollars, and then you sit down with her and she’s so real.”

“There’s nothing Lory Masters could need or want or ask me to do that I wouldn’t do for her,” says Atkinson, who lived in Loryland for decades. “She’s like family, and I am only one of many people that feel that way about her.”

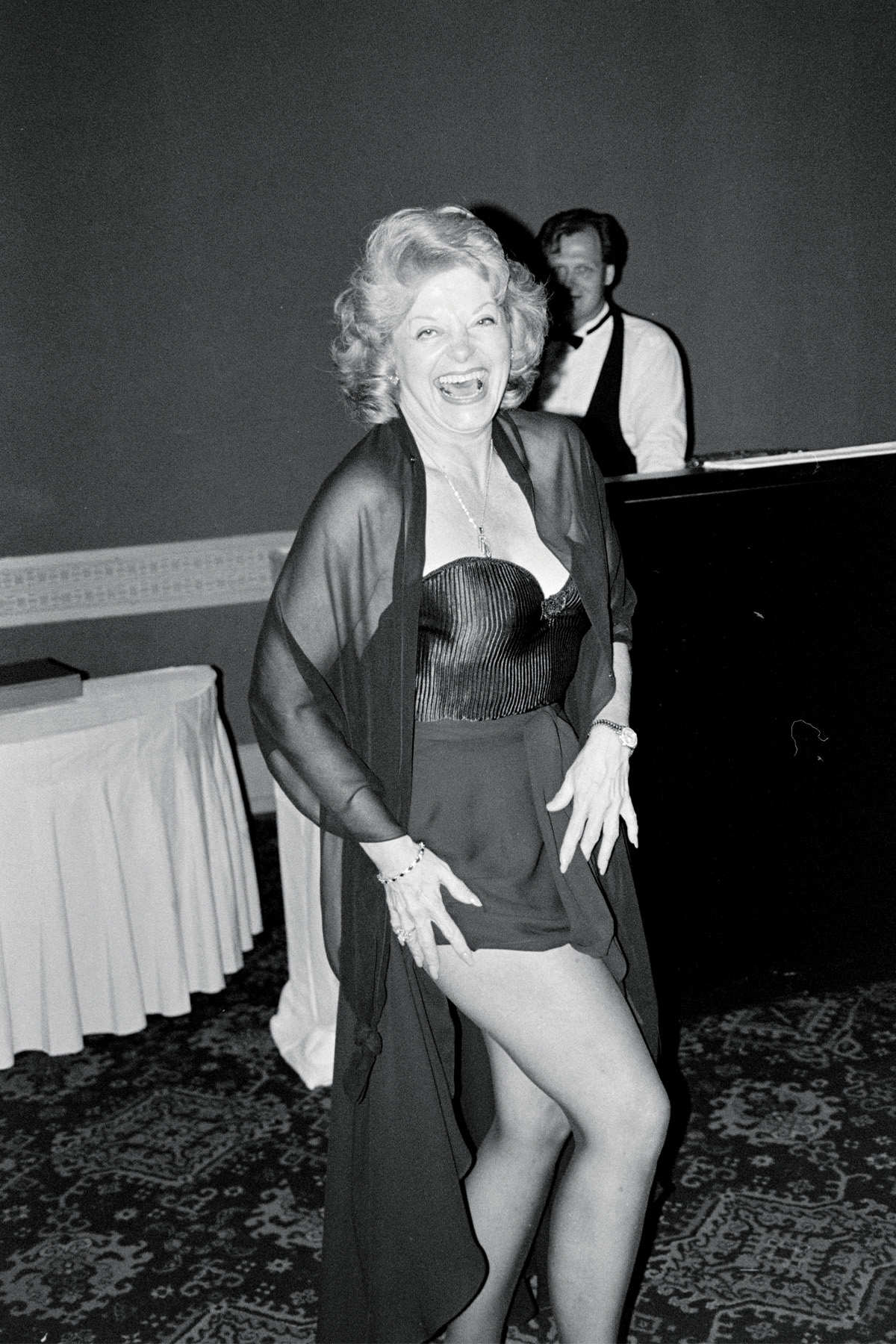

One of Olson Roper’s first memories of Masters was made inside a foggy, disco-lit bar on Oak Lawn in the ’90s, when she was 19. There weren’t as many established organizations then, and the LGBTQ community often held fundraisers in the bar. The music was loud, and women danced as Masters strode onto a stage. Then the lights came up, and the music stopped. People fell silent. Olson can’t recall the cause, but she remembers the women holding hands in a circle and passing a bucket to collect money.

“We were giving what we had and were moved by this emotional connection and sadness and hope at the same time,” Olson Roper says. “Lory was at the center of it.”

This story first ran in the July issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Force of Nature.” Write to [email protected].

Author

Will Maddox

Will is the managing editor for D CEO magazine and the editor of D CEO Healthcare. He’s written about healthcare…