In 1984, George Michael released a song called “Freedom” with his pop duo Wham! Six years later, he put out one of his own called “Freedom! ’90.” And six years after that? A song called “Free” closed his third solo album, “Older.”

The specifics of the liberation he’s describing in each tune vary; so too did the shape of the British singer’s stardom at the time he wrote each of them. But to listen to these songs now — half a decade after Michael’s shocking death at age 53 and amid a swelling of interest in his work tied to several new retrospective projects — is to confront the fact that the reason he kept singing about freedom is because he kept not finding it.

“George’s life was shot through with disappointment,” says James Gavin, author of an exhaustive and empathetic biography, “George Michael: A Life,” published this week. “For all the tragedy I uncovered in writing this book, though — for all the childhood sadness and the unhealed wounds from his relationship with his father and from losing the great love of his life to AIDS — none of it in the end overrode the joy in his music.”

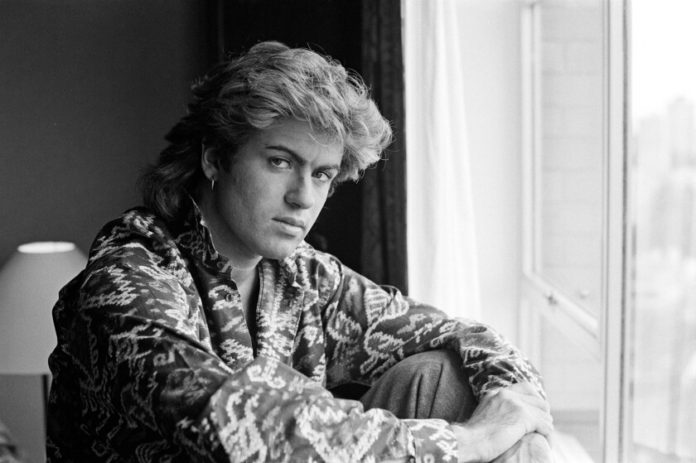

George Michael during Wham!’s 1985 world tour.

(Michael Putland / Getty Images)

Gavin is right about that: From “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” to “Faith” to “I Want Your Sex” to “Fastlove,” Michael’s classic songs practically vibrate with exuberance, his from-the-guts singing pitched between a snarl and a coo, the cleverly detailed grooves (which he devised as his own writer and producer) pushing ever forward. Even his slow, sad ones — “Careless Whisper,” “One More Try,” “Praying for Time” — have a kind of mournfully ecstatic quality, as though he couldn’t bear to stop luxuriating in their melancholy.

The purity of emotion in Michael’s music, not to mention his good looks and quick wit, is what made him a superstar in the ’80s and ’90s, with 21 top-10 hits (including 10 No. 1s) on Billboard’s Hot 100. In 1985, he and his Wham! partner Andrew Ridgeley became the first major Western pop act to play in China; in 1989 Michael’s solo debut, “Faith,” won album of the year at the Grammy Awards.

Yet compared with the other titans of the MTV era — Madonna and Michael Jackson and Prince and Bruce Springsteen — Michael’s legacy seems less secure today than those of his onetime peers with the Broadway shows and the Hollywood biopics and the obvious stylistic inheritors. (Try to name a current artist who comes anywhere near as close to emulating George Michael as the Weeknd does Michael Jackson.)

What makes his phantom-ish presence, at least in this country, especially curious is that in many ways Michael was laying important groundwork for pop stars to come, even if he’s not the first inspiration they cite. Think of Michael’s fluid performance of gender for an audience of adoring female fans and the path that opened for Harry Styles. Think of his legal battle with Sony Music over what he considered an unfairly restrictive contract and the precedent it set for Taylor Swift to wage war with Scooter Braun. Think of his successful transition, later replicated by both Styles and Swift, from a lucrative gig in the bubblegum factory with Wham! to a widely acknowledged role as a grown-up auteur beginning with “Faith.”

There’s also, of course, the temptation to view Michael as a queer icon, which to many he certainly was.

“George was a huge pioneer,” says songwriter Justin Tranter, who’s penned hits for Selena Gomez and Justin Bieber, among many others, and who serves as a board member of GLAAD. “I mean, Wham! was the most fabulously gay thing that ever happened.”

But as Gavin documents in his deeply researched book, for which he spoke with more than 200 people in the singer’s orbit, Michael was an imperfect spokesperson — a man for whom the burden of coming out of the closet felt as oppressive as the burden of staying in.

Why the reluctance? Gavin describes the crushing fear of his father’s disapproval, an idea shared by manager Michael Lippman, who oversaw the singer’s career (with Rob Kahane) during “Faith” and was managing him again at the time of his death. “George didn’t want to come out to his family,” Lippman tells The Times.

But there was a clear professional risk too for a pop heartthrob who’d built an audience in part through his deft use of traditional masculine iconography. Here in 2022 we’d like to think that pop music has shed its old prejudices — that a gay musician would no longer have to confront the kinds of choices Michael did. Yet Tranter points out that “we’ve still never — ever, ever, ever — had a superstar who started their career out of the closet.”

Freddie Mercury, Elton John, Melissa Etheridge, Sam Smith, Lil Nas X — each was able to own the fullness of their identity only after they’d attained success. And once they came out, their queerness came to define their music in the eyes of the public, a fate Michael actively resisted; for some, like Smith, coming out has arguably dampened the trajectory of their careers. So it’s not hard to understand why Michael declined to engage the question or why some who worked with him sought a kind of plausible deniability.

“People would ask me if he was gay and I didn’t have the answer,” Lippman says. “I wasn’t being coy.”

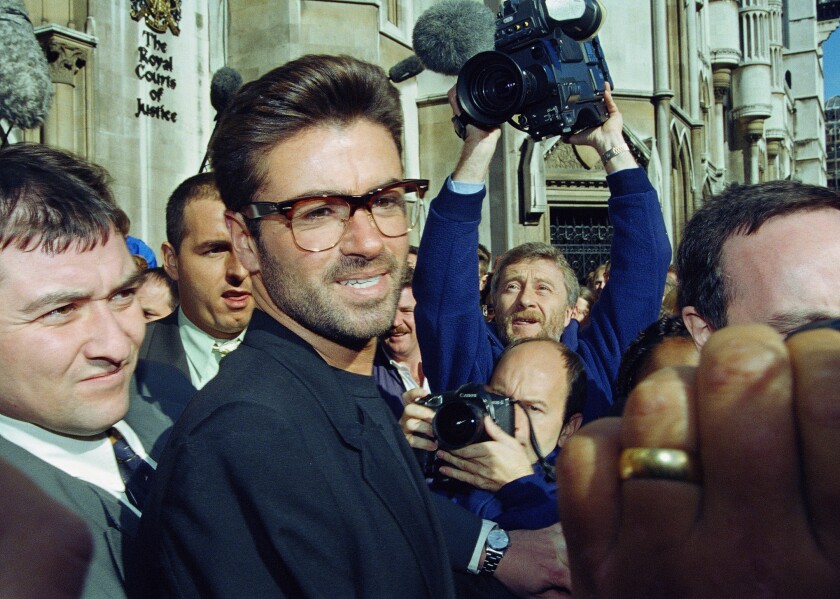

George Michael at the start of his legal action against Sony Music Entertainment in 1993.

(Alistair Grant / Associated Press)

Given that context, 1996’s “Older” is particularly fascinating to revisit; indeed, it was the first of Michael’s albums to catch the interest of Gavin, whose previous books told the stories of Lena Horne, Peggy Lee and Chet Baker. Set to be reissued in August as a deluxe box set, “Older” came out two years before Michael was famously outed as a result of his arrest on charges of lewd conduct in a men’s room at Beverly Hills’ Will Rogers Memorial Park. Yet the songs, which Gavin compares to a “set of diary entries,” tenderly depict his romantic relationship with Anselmo Feleppa, whom he’d met in Brazil in 1991 and who died a mere two years later.

Michael’s singing on tunes like the sumptuous, bossa-nova-inflected “Jesus to a Child” is the gentlest he ever recorded even as the song’s lyrical conceit skirts various cultural taboos. “I thought it was really courageous,” says Lenny Waronker, the veteran record exec who led Michael’s then-new label, DreamWorks Records, which launched with “Older’s” release. “He was an artist reaching out to do something that wasn’t necessarily predictable.”

According to Gavin, “Older” was Michael’s favorite of his albums — and also the one where “gay people knew George was speaking to them,” even if its sometimes-coded language may have limited its broader standing as a queer touchstone.

The singer’s attempt to control the way his work was perceived — to control the way he himself was perceived — was a through line in his life, and it remains one now that he’s gone. Last week, Michael’s estate released an expanded edition of a documentary titled — what else? — “George Michael: Freedom,” which he directed with his lifelong friend David Austin before Michael was found dead at his home on Christmas Day in 2016.

A quick-moving account of his rise to global celebrity, the new cut of the film improves slightly on the original, with the addition of some touching home-movie footage of Michael and Feleppa to go with all the gushing talking-head interviews. But it’s still a shallow gloss on a life of considerable complexity. Unlike Gavin’s book, the movie has virtually nothing to say about the final decade and a half or so of Michael’s life, when he struggled mightily to find a creative spark (and struggled even worse with substance abuse).

Of the decision to put the film in theaters just days before the publication of his unauthorized biography, Gavin — who’s heard the estate “is not at all happy with the book” — says, “Make of that what you will.” The writer persuaded scores of Michael’s collaborators and intimates to go on the record with him, though Austin and a few others declined to talk. (Austin likewise declined to comment for this story.) Gavin is philosophical about the suspicion he encountered.

“Because George lived so much of his life in hiding, and because so much scandal shrouded his later life, anyone who pops up as I did asking questions is bound to be seen as one of those guys from The Sun,” he says, referring to the gossipy British tabloid.

Yet modern pop stardom relies to some extent on a willingness to let one’s public image loose in the slipstream of social media, which perhaps is why George Michael, or the idea of him anyway, feels less connected to our time than he should.

Wham!’s George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley perform at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in1983.

(Pete Still / Redferns via Getty Images)

Lippman, who ordered Gavin’s book on Amazon — “I’m curious,” he says — insists that he has a plan to uphold the singer’s legacy. “It’s been very slow and quiet because of his family,” the manager says. “It’s a question of doing the right things at the right time.”

Asked if material exists in a vault like the one Prince left behind, Lippman says, “He was working on stuff, but nothing was really finished. And until George finished the music, it wasn’t real.”

But maybe the effort to keep Michael’s spirit alive won’t have to come from the top down. Tranter, who identifies as gender nonconforming and uses they/them pronouns, says that at least once a month on TikTok they encounter a clip from Michael’s 2004 interview with Oprah Winfrey, when the singer was making the rounds to promote that year’s “Patience.”

“Are you worried about American fans — now even, with this new album — accepting you as a gay artist?” Winfrey asks.

“I have to be totally straightforward here,” Michael replies. “I’m not really interested in selling records to people who are homophobic.” He says it easily, betraying none of the effort it took him to reach such a conclusion. Then he smiles.