Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

Derek Jeter is driving through his local coffee shop on his way to loanDepot park, where he is four years into his tenure as chief executive officer and part owner of the Miami Marlins. Caffeine helps, but so would a little more hitting.

In each of his four seasons, the Marlins have been a bottom three team in the National League in slugging, including last season when they surprisingly slipped into the playoffs and won a wild-card series against the Cubs. They rely on superb young pitching. All but seven of their games over the past three years have been started by pitchers in their 20s.

Without much power, and often engaged in tight, low-scoring games, the Marlins must play the way Jeter did: fundamentally sound team baseball. Lapses are costly, such as two nights earlier when 23-year-old Jazz Chisholm was thrown out trying to steal third base with two outs and the team’s best home run hitter, Adam Duvall, at the plate. Miami lost, 2–0.

“I’m thinking to myself, What are you doing?” Jeter says. “But then I’m like, well, hold on a minute. I did the same thing.”

Yes, Jeter made mistakes, though the overwhelming narrative of his Hall of Fame career is as one of the savviest, winningest players in baseball history. Jeter is the only player to play in more than 1,600 winning games and win five world championships. He turned winning into a convenience, like this coffee run through the drive-through, which he begins with a “please” and ends with a “thank you” and “have a great day.”

Gay Talese wrote as the Jeter legend coalesced, “He’s rather unique for a young man in the 1990s … In this era of boorish athletes, obnoxious fans, greedy owners and shattered myths, here’s a hero who’s actually polite, and that has to have come from good parenting. You can’t compare him to Joe DiMaggio, for DiMaggio didn’t have bad manners—he had no manners. Where have you gone, man with manners? Here you are, Derek Jeter.”

The wonder of the Jeter aesthetic is that he seemed to arrive that way in the big leagues—a polished winner right out of the box. He would like to set the record straight on that notion.

Derek Jeter is four years into his tenure as chief executive officer and part owner of the Miami Marlins

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

“I’ll give you a story,” Jeter says.

Well, now. This is akin to Garbo granting an interview or the Sphinx allowing direct passage into Thebes. Jeter is about to tell a story about himself from 1996, his rookie season and the birth year of the greatest baseball dynasty of the modern game. Once the Yankees put Jeter at shortstop and Joe Torre in the dugout as manager, they won four World Series titles in five years, a run not seen since 1953, and a run made more astounding by the added exit ramps and tripwires that come with expanded playoffs.

“You’d have to ask Mr. T,” Jeter says, referring to Torre, about whether to print the story. “But I don’t think he would share it like this.”

In Jeter’s rookie season, MLB revenues were $706 million. In his last season, 2014, they had soared to $9 billion. No player carved a more impactful role in the sport’s greatest economic expansion than Jeter, especially because he filled prime-time television screens virtually every October in a baseball version of Game of Thrones before there was a Game of Thrones. Jeter is the all-time postseason leader in games, at bats, hits, runs, total bases, doubles, singles and video highlights. His jersey is the best-selling jersey of all time.

Ninety-six is the origin story. This is its 25th anniversary, a milestone made more special by Jeter’s pandemic-delayed induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame this September. Excluding Mozart’s tour of Europe at age seven, never has there been a rookie season more charmed than that of Jeter in 1996. Jeter was 21 on Opening Day when he hit a home run on his second swing and made a spectacular running catch of a pop fly. It was the start to a yearlong coronation as the prince of the city, if not all of baseball. Jeter hit .314 in the regular season and .361 in the postseason, won the World Series, was unanimously named Rookie of the Year, and by the end of the year was taking in Knicks games with supermodel Tyra Banks.

You can look before and after Jeter and never find another rookie season like his. Jeter is the youngest rookie shortstop to hit .300 and win the World Series. It was implausibly perfect—except for the story Jeter wants to tell with Mr. T’s permission.

“Of course,” Torre says. “I remember.”

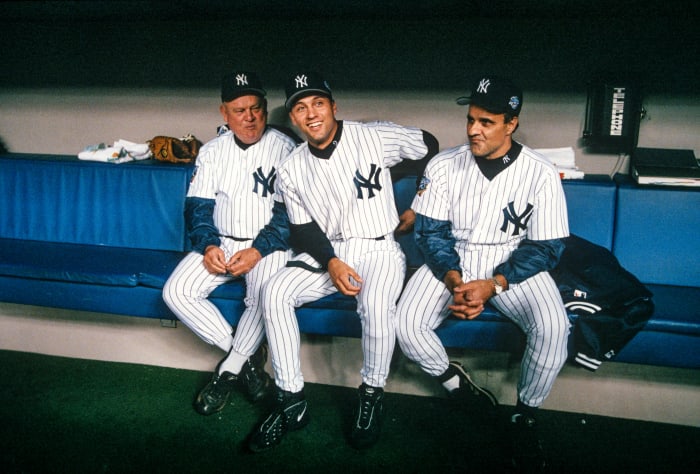

Derek Jeter and manager Joe Torre, who Jeter calls “Mr. T” and says is “like a second father to me.”

Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images

The Yankees are playing one of their final spring training games in Florida before the opener in Cleveland. Jeter remembers it was a game in Winter Haven, Fla., against Cleveland. By then Jeter, despite a rocky camp, was locked in as the New York starting shortstop. The Yankees had moved their incumbent shortstop, Tony Fernandez, to second base, only to see Fernandez break his elbow, thus ending even the semblance of competition for Jeter.

“I’m still concerned about whether or not I’m going to make the team,” Jeter says. “And there was a runner on first base. Two outs.”

A ground ball is hit to the right of first baseman Tino Martinez, who fields the ball and turns to throw to second base for the third out. But there is a problem. Martinez has no one to throw to.

“I didn’t cover second base,” Jeter says. “I assumed he was going to throw to first [to the pitcher covering]. I didn’t cover second. We ended up getting out of the inning.

“And you know how in spring training you can sit on the field? The manager will sit on the field sometimes? And if you’re on deck you can sit next to him.”

Jeter was on deck the next inning. He sat next to Torre on the warning track next to the dugout.

“Mr. T, in only the way he knows how to do it … he didn’t look at me and he …”

Jeter starts laughing as the memory of Torre’s manner and words wash over him again like the tide returning. Torre, per Jeter’s condition, picks up the story.

“I told him, ‘We’re leaving here in a couple of days. Get your bleeping head out of your ass.’ ” (Torre, of course, did not say bleeping.)

“You know, Mr. T is like a second father to me,” Jeter says. “And he said that and I was like, ‘Oh, God.’ I didn’t know how to take it. Does that mean I’m going with the team? I mean, did I just screw up my chance again? I wouldn’t write the language if he didn’t approve it, but that’s how spring training went for me.”

If you want the prequel to The Charmed Season, you must go back a bit further—to that offseason and the Yankees’ player development complex in Tampa. Jeter moved to Tampa that winter so he could train at the complex, where he often trained with Martinez and third baseman Wade Boggs, who lived in the area.

“In Miami, you see a lot of players nowadays do it,” Jeter says. “The Yankees work out in Tampa. Guys with us live close to Jupiter. I was one of the first ones to move, to relocate to Tampa to work out with the player development staff. I did it because I thought if a decision came down between me and someone else, they could see how hard I was working. So I moved there full time.”

When camp opened, the Yankees did not hand Jeter the job, but it was so obvious they wanted him to start that by Feb. 22 Fernandez had already told reporters he wanted to be traded. General manager Bob Watson said he would not shop Fernandez.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

“We have to find out if Derek is our shortstop,” Watson said, “and I’m not going to rush and make a trade until then.”

Says Jeter, “My mindset going there was just to win a job. I thought I had an opportunity. I know Mr. T had come out and said I was going to be the shortstop, and I said I looked at it as, I had an opportunity to win a job. I never looked at it like I had anything made. It was, bottom line, trying to win a job.”

His task did not go well. The first time Jeter touched the ball in an intrasquad game, he threw the ball away for an error. The first time he touched it in an exhibition game, he threw the ball away in his haste to avoid a slide from Kenny Lofton of Cleveland.

“I can tell you that I struggled,” Jeter says. “I thought for sure I was going to get sent down. I do think they probably would have sent me down, but Tony Fernandez broke his arm toward the end of spring training, and I basically felt like they were stuck with me. They didn’t have a choice.”

Torre saw something in the kid.

“Not that I know more than anybody else,” Torre says, “but you noticed on a day-to-day basis that he was not this skittish kid. He may have been pressing, but he had a good look in his eye all spring. That look was verified in the playoffs.”

Yankees owner George Steinbrenner showed uncharacteristic patience with Jeter, telling reporters March 2 that spring, “I would not have gone with a Jeter in the past. I think I’ve changed. I was too demanding, too hasty.”

His patience ended 22 days later when Fernandez broke his elbow—on the same day Jeter made two more errors. The Yankees lost their safety net behind Jeter. To acquire one, Steinbrenner considered a trade with Seattle for infielder Felix Fermin. Mariners general manager Woody Woodward asked for either of two of the Yankees’ best young pitchers, Bob Wickman or Mariano Rivera. Steinbrenner pushed for the deal. Torre, Watson and Brian Cashman, then the assistant general manager, pushed back. They spent almost three hours in a meeting in Torre’s office in Tampa convincing Steinbrenner not to make the trade and to stick with Jeter. They won out.

“I never talked to anyone in the front office about it,” Jeter says. “I think they had no choice. This is just me—this is my opinion—I think they probably thought, ‘Hey, let’s give him a little time and see how it goes.’ But if Tony didn’t break his arm, I think I would have been shipped out of there.”

Jeter quickly rewarded their faith. His Opening Day performance “helped relax me,” he says. “Number one, I don’t care if it’s your rookie year or your 20th year, the first of anything is hard to get. And I know there’s a lot of questions going into the season, and it was good for me to have a good opening day. I’m not saying that, ‘O.K., I’ve got it made now.’ But I think mentally you know that ‘I can have success at this level. I can do it.’ ”

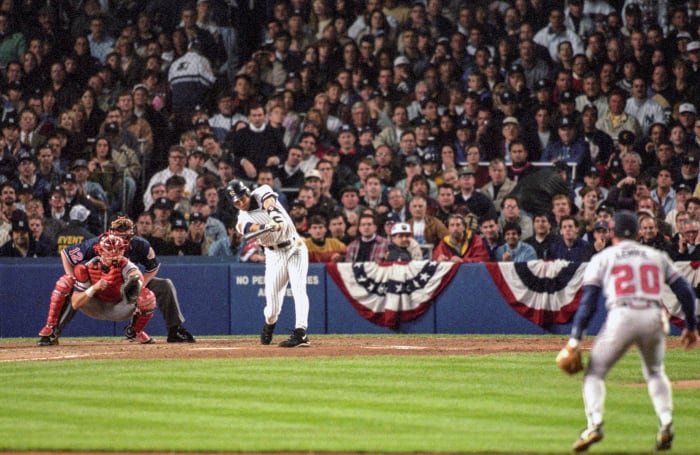

Derek Jeter hits a home run on Opening Day in 1996 at Jacobs Field in Cleveland.

David Liam Kyle/Sports Illustrated

Batting ninth mostly, Jeter hit .340 in his first 15 games but ended April at .274. Not until Aug. 5 did his batting average resurface above .300. In a primer for the postseason, Jeter slashed .343/.383/.459 down the stretch while scoring 51 runs in those 51 games and establishing himself not only as the team’s best player, but also as the team’s competitive touchstone that he would be for the next 18 years.

“Never before had I seen anything like that,” Torre says about how a veteran team relied so heavily on a rookie. “I may have made a comment about a guy or two in the past, but this guy was there every single day to really stand up—not only to stand up to the pressure of being a rookie, but toward the end of the year guys were counting on him to get something started or knock in a run. It was so unusual.

“And the cherry on top was this was New York. You’ve seen guys melt away from the pressure and expectations in New York. He had a good upbringing. His parents did a wonderful job. They raised him to be ready for this situation.”

Says pitcher David Cone, “As veterans, you look for reasons to get on young players to make sure they stay humble. Believe me, we looked for anything to get on Derek about. The way he carried himself, the way he dressed, the way he spoke … and we found nothing. It was truly remarkable how at 21, 22 he was so completely ready to be a major leaguer and a star.”

There was one rare moment when Jeter showed his youth. It was Aug. 12. The Yankees were tied, 2–2, in the eighth inning against the White Sox. With two outs and Cecil Fielder at the plate, Jeter tried to steal third base. He was thrown out—just as Chisholm was for his team this year. In a rare display of anger in the dugout, Torre threw a clipboard over the rookie’s mistake.

“I was mad at myself for trusting him,” Torre says. “I gave him too much rope. I remember he had to stay on the field—it was the third out. I remember saying to [bench coach Don Zimmer], ‘I’m not going to talk to him today. I’ll talk to him about it tomorrow. We have a game to win.’ ”

Says Jeter, “I knew I was wrong. I knew I was in trouble. From what I understood, Mr. T was going to wait to speak to me after the game or the next day.”

After the inning ended, he squeezed himself into the tiny space between Torre and Zimmer on the bench.

“I hit him in the back of the head and said, ‘Get outta here,’ ” Torre says. “He knew. He was going to take his medicine. He was so refreshing. I know at his age I didn’t have anything like the maturity that he had as a player.”

Derek Jeter sitting between Yankees bench coach Don Zimmer (left) and manager Joe Torre.

Rich Pilling/MLB/Getty Images

October completed The Charmed Season, though it began poorly. In a loss to Texas in Game 1 of the American League Division Series, Jeter, batting ninth, left six runners on base with a strikeout, pop fly and ground ball. The headline the next morning in the Daily News would refer to “Jeter’s Jitters.” After the game Torre mulled the need to talk to his rookie shortstop the next day.

“I was in my office after the game,” Torre says, “and I was thinking, I don’t know. I’ll get a feel for it and see how he is. All of a sudden, as he’s leaving the clubhouse, he peeks his head inside my door and he says, ‘Get some rest, Mr. T. Tomorrow is the most important game of your life.’ I thought, My goodness. He’s special. There was a trust he earned at a very early age that is so rare.”

Jeter kept up his running postgame gag with Torre throughout the playoffs.

“It wasn’t like I went home and said, ‘Oh, man, I had a bad game. What’s going to happen? Can I play in the playoffs?’ ” Jeter says. “No. For me it’s like, ‘That’s over with.’ And the postseason is when it’s fun.”

The next night Jeter became the youngest Yankee to get three hits in a postseason game at Yankee Stadium as New York began its run to the world championship with a 5–4 win in 12 innings. In a scene repeated so many times you might have been forgiven for thinking Jeter kept batting out of order, the rookie was in the middle of the game’s denouement. He started the winning rally with a single and scored the winning run. The Yankees won 11 games that October, only once without Jeter scoring or driving in a run. His key contributions also included:

• Starting the winning rally in the ninth inning of ALDS Game 3 with a single.

• Hitting the famously fan-aided eighth-inning home run that tied ALCS Game 1 against Baltimore

• Starting the winning eighth-inning rally with a double against Orioles ace Mike Mussina in ALCS Game 3

• Leading off ALCS Game 4 with a double, which preceded a home run by Bernie Williams that gave New York a lead it never lost

• Contributing a single in the six-run third inning that salted the ALCS Game 5 clincher, a game that ended with Jeter’s throwing out Baltimore shortstop Cal Ripken

• With the Yankees trailing Atlanta in the World Series two games to none, dropping a first-inning sacrifice bunt that helped give New York its first lead in the series, and starting a two-run eighth inning with a single

• Down 6–0 in World Series Game 4, starting a three-run rally in the sixth inning with a single and starting the winning rally in the 10th inning with a single

• Driving in one run and scoring another in the World Series Game 6 clincher.

In 15 postseason games Jeter slashed .361/.409/.459 and reached base in all of them but one. The only trouble he encountered involved parking in Manhattan. On the morning of the eve of the World Series, Jeter was flummoxed when he could not find his leased Mercury that he had parked the night before in front of his apartment building on Second Avenue.

“I’m walking up and down the street in Manhattan,” he says. “Two or three blocks in all directions. I know I parked it here. I’m trying to find my car. And sure enough, they towed it. Parking tickets. Lots of parking tickets, man. So they towed my car.

“The thing that stands out the most from ’96—this was prior to interleague play. So we’re playing the Braves in the World Series. I had never seen the Braves. The only time I saw the Braves was on television when I was younger. It was [Greg] Maddux and [John] Smoltz and [Tom] Glavine and Fred McGriff and Chipper Jones being drafted as a shortstop a couple of years before me and following his career. And you go out there for the pregame introductions and it’s like, Man, this is the Braves. These are the world champions.

“I remember we had our team meeting before the series, and Mr. T saying, ‘O.K., this team is going to be better than any team you played all year.’ And I go, ‘Oh …’ We’re in the World Series. That stands out. So that was like an intro into, ‘O.K., now it’s the World Series,’ and not knowing anything about a team you’re playing.”

Derek Jeter batted .361 and reached base in all but one of his 15 postseason games during The Charmed Season.

V.J. Lovero/Sports Illustrated

Jeter played the biggest games with a preternatural calm. There was a consistency about him derived from the disciplined way he was raised by his parents, Dorothy and Charles, who met in 1972 in Frankfurt, Germany, while both were stationed there with the U.S. military. His parents had him sign a “contract” vowing respectful behavior and proper attention to schoolwork. When Jeter was 10 years old, he decided he would be the shortstop for the New York Yankees. It became possible only because the Astros (Phil Nevin), Cleveland (Paul Shuey), Expos (B.J. Wallace), Orioles (Jeffrey Hammonds) and Reds (Chad Mottola) all passed on using one of the top five picks of the 1992 draft on the skinny shortstop from Kalamazoo Central High.

When Jeter reported to the Yankees’ player development complex in Tampa, his first order of business was to find a wood bat to use in pro ball. He had played exclusively with a metal bat as an amateur. Jeter stood before a huge bin of wood bats. One by one he picked out bats, holding them in his hands like a finicky shopper in the produce section, searching for the one that most resembled his high school bat in size, weight and taper. The one he decided on was a Hillerich & Bradsby Louisville Slugger P72 model—33.5 inches, 31 ounces—with its thin handle, medium sized barrel and balanced weight.

Jeter would go on to take 15,404 appearances as a professional, including his record 734 in the postseason and 2,068 in the minors. For every one of them he used the P72. (In 1997 he moved to a 34-inch, 32-ounce P72.) The model dated to 1954, when it was created for Leslie Wayne Pinkham, a minor league catcher. In 2014, Hillerich & Bradsby retired the P72 in Jeter’s honor, an unprecedented tribute in the bat maker’s 137-year history.

Most players, to escape the clutches of a slump, to co-opt the karma of a hot-hitting teammate or simply to pursue the chance of something better, occasionally switch bat models. That Jeter used one model for 22 years spoke to his consistency of purpose, which especially served him well in his first postseason.

Yankees third baseman Charlie Hayes said during that October run in 1996, “The thing that sets Derek apart from everybody else is that he’s not afraid to fail.”

Asked what that observation meant, Jeter says, “One thing you always have to understand, at least the way I looked at it, in any situation I’ve made an error before. I struck out before. I’ve played basketball and hit game-winning shots and shot air balls. I’ve been on both sides. So the way I’ve always looked at it is, what’s the worst thing that could happen? You know, what is it? You strike out?

“But I’ve always looked at it the other way. My mind always went to being successful and it went back to times when I had success. So in that sense I didn’t think about, so what if I failed? I was just never afraid of it.

“I think what helped me was being around the year before, in ’95, and getting to see what the atmosphere was like, and actually not playing in ’95 made me want to play that much more. For me it was just another game. I didn’t treat the postseason any differently.

“I liked it because in your mind the lights are brighter, there are more people in the stands, more people are paying attention. I don’t want to say it’s bigger, but people pay more attention to every situation. I liked the attention, the spotlight, that was on postseason games.

“But I didn’t personally change. I wasn’t now like all of a sudden going to change my routine, or I’m going to show up 30 minutes earlier, looking at different scouting reports or studying them more. No, no, no. I just approached it like any other game.”

How do you follow such a season, especially when companies begin lining up to secure Jeter as an endorser and the fan mail comes in boxloads? Two months into the following season, Torre called Jeter into his office while the team was playing in Toronto.

“Here he was, he won the rookie of the year and the World Series,” Torre says, “and it’s New York and he’s single and good-looking. You think about all those things, and I just wanted to make sure his priorities were right. I told him how important it was to stay focused.

“He looked me right in the eye and basically acknowledged everything I was saying. I never had to worry about him. His life was baseball. Nobody had to remind him. I still marvel that here was a guy that never disappointed you. That’s saying a lot.”

Derek Jeter hits an RBI single in Game 6 of the 1996 World Series at Yankee Stadium.

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

Twenty-five years have passed since the Jeter Era began. The phenom from 1996 turned 47 years old on June 26. He and his wife, Hannah, have two daughters.

His parents kept a scrapbook in 1996. Jeter has a few signed team baseballs from that year, a glove and a World Series trophy. Someday, he says, he will build a memorabilia room for all the keepsakes of his career. What, he is asked, is the most enduring memory he has from The Charmed Season?

“You know, one thing I remember, and I still remember it to this day, clear as day … ,” he says. “I was eating at a restaurant, called Cronies, on the Upper East Side, after a game. Late after a game. And I saw for the first time somebody wearing a T-shirt with my name and number on it—outside of the ballpark.

“I can’t tell you when in the season it was, but I thought that was the coolest thing. It’s different when you’re at the field, because a lot of people have jerseys and you may see your name and number here and there. But that was the first time I saw it outside the park. And I was like, ‘Man, oh, man. This is what you dream of.’

“Obviously throughout your career you see more and more people wearing it. And you always appreciate someone wearing your jersey, still to this day. You still appreciate it. But you never forget your first time.”

More years have passed since 1996 for Jeter than the years that brought him to that launch party of a season. He seemed so ready-made for stardom that it is hard to imagine Jeter, with his accumulated wisdom now, would have any advice if given the chance to talk to his younger self. And yet, he says, there is something.

“You know what I would say?” he says. “The one thing I did in my last year was I kept a journal. Every day. Could be one sentence, two sentences. Could be about anything. How I was feeling. It didn’t even have to be about the game.

Derek Jeter tips his cap to the crowd in his final game at Yankee Stadium on Sept. 25, 2014.

Porter Binks/Sports Illustrated

“And I wish I would have done that in the beginning of my career. Because there are so many things you forget. So many things. I played a long time. But it goes fast.”

In the last game of The Charmed Season, Jeter came to bat against Maddux in the third inning of World Series Game 6. The Yankees led, 1–0. With Joe Girardi on third base, Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox brought his infield in. Jeter looked at two balls from Maddux, then swatted a base hit into center field to drive in Girardi.

Cox ordered a pitchout on the next pitch, thinking Jeter might try to steal second. He was wrong. Instead, Jeter ran on the next pitch, stealing the bag so easily that catcher Javy Lopez did not bother making a throw to contest it. Jeter scored on a two-out single by Williams. It became the deciding run of a 3–2 Yankees victory.

At 22 years and 122 days old, Jeter became and remains the youngest player with a run, an RBI and a stolen base in helping to win a World Series clincher. It was an unprecedented end to an unprecedented season. When Hayes caught a foul pop fly for the final out, Jeter, trailing the play, immediately jumped for joy with both hands over his head. A version of such celebratory joy he would repeat four more times, making him the only player in the expansion era (since 1961) to be on the field for the last out five times. Because it was first, because he was a rookie batting ninth and because expectations were modest, only 1996 rings so clear with the wonder of discovery.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

• Pete Sampras Is Doing Just Fine