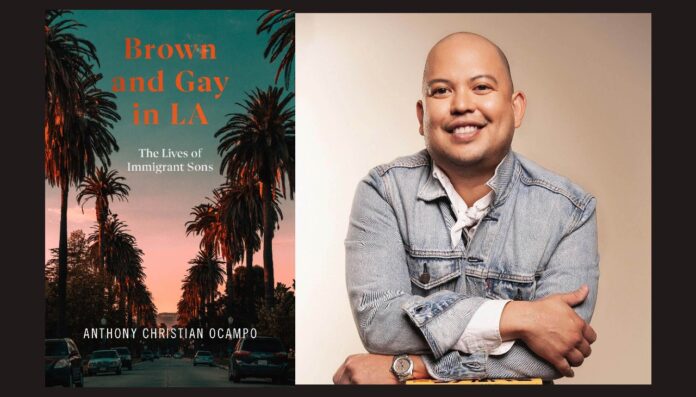

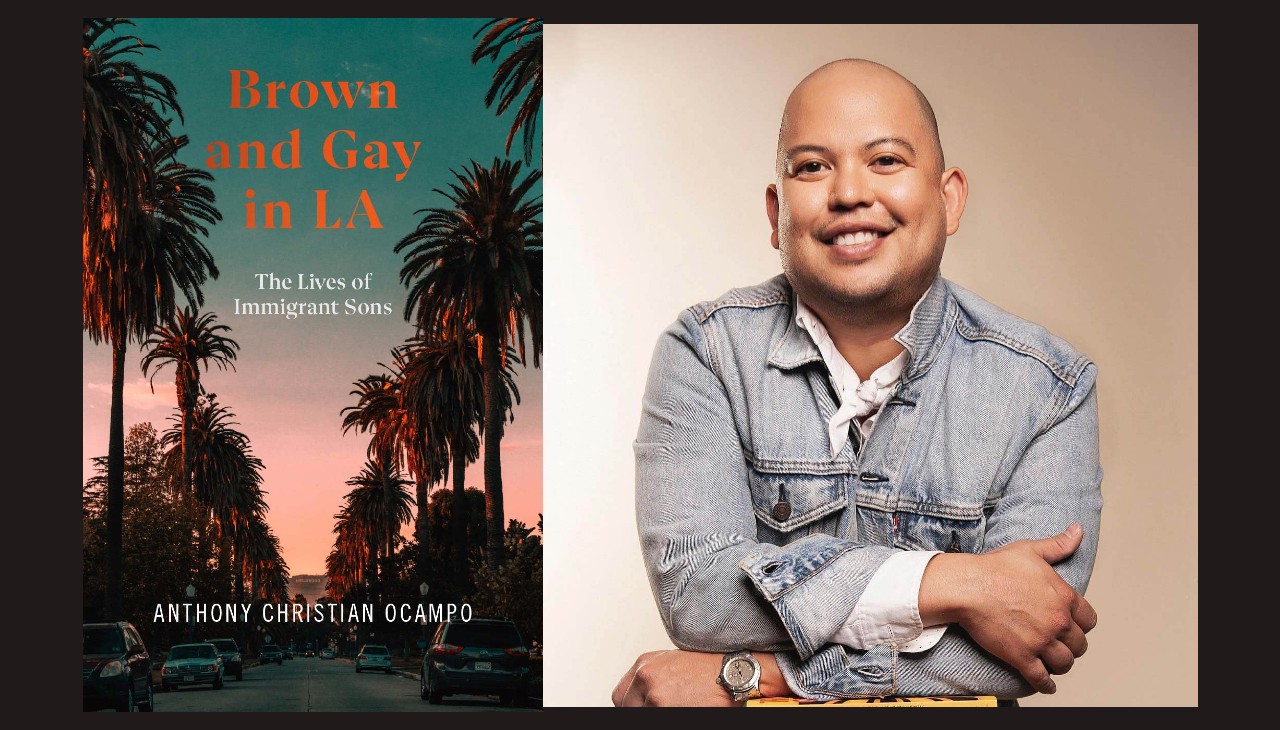

Anthony Ocampo was born and raised in Los Angeles, a city where it is queerness is generally accepted and celebrated thanks to Hollywood. But for a gay son of Latino and Filipino inmigrants like himself, it wasn’t that easy.

In “Brown and Gay in LA: The Lives of Immigrant Sons”, Ocampo, a Sociology professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, details his own story of reconciling his queer Filipino American identity and those of men like him.

He shows what it was like for these young men to grow up gay in an immigrant family, to be the one gay person in their school and ethnic community, in which men profiled here maneuver through family and friendship circles where masculinity dominates, gay sexuality is unspoken, and heterosexuality is strictly enforced. For these men, the path to sexual freedom often involves chasing the dreams while resisting the expectations of their immigrant parents—and finding community in each other.

Brown and Gay in LA is an homage to second-generation gay men and their radical redefinition of what it means to be gay, to be a man, to be a person of color, and, ultimately, what it means to be an American.

“The idea that gay men aren’t men is a fallacy,” he told NBC. “That was something that they weren’t always afforded the opportunity to do because people would call them f—-, or people would say you’re not a real man because you like other men.”

RELATED CONTENT

They also challenge the preconceived notion of an American being a white middle class person.

“When you think of America, you hardly ever think about the queer, gay children of immigrants, even though they are very much part of the mosaic of this country,” he told NBC.

In 2018, Ocampo published The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race, an essay to show that what “color” you are depends largely on your social context. Filipino Americans, for example, helped establish the Asian American movement and are classified by the U.S. Census as Asian. But the legacy of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines means that they share many cultural characteristics with Latinos, such as last names, religion, and language.

As Ocampo exposes, the Filipino story demonstrates how immigration is changing the way people negotiate race, particularly in cities like Los Angeles where Latinos and Asians now constitute a collective majority. Amplifying their voices, Ocampo illustrates how second-generation Filipino Americans’ racial identities change depending on the communities they grow up in, the schools they attend, and the people they befriend.