Welcome to ABC Arts’ monthly book column. Each month, we present a shortlist of new releases read and recommended by The Bookshelf’s Kate Evans and The Book Show’s Claire Nichols and Sarah L’Estrange — alongside freelance writers and book reviewers. This month, we’re sharing recommendations from Declan Fry.

All four read voraciously and widely, and the only guidelines we gave them were: make it a new release; make it something you think is great.

The resulting list includes the latest from the bestselling author of Booker Prize finalist Room (later adapted by the author into a movie starring Brie Larson); a sci-fi debut set in Melbourne 60 years into the future; a meditation on queer, interracial love in 50s Australia; and two essay collections — one about the power dynamics inherent in translation, and the other a celebration of the work of writers of colour from Australia.

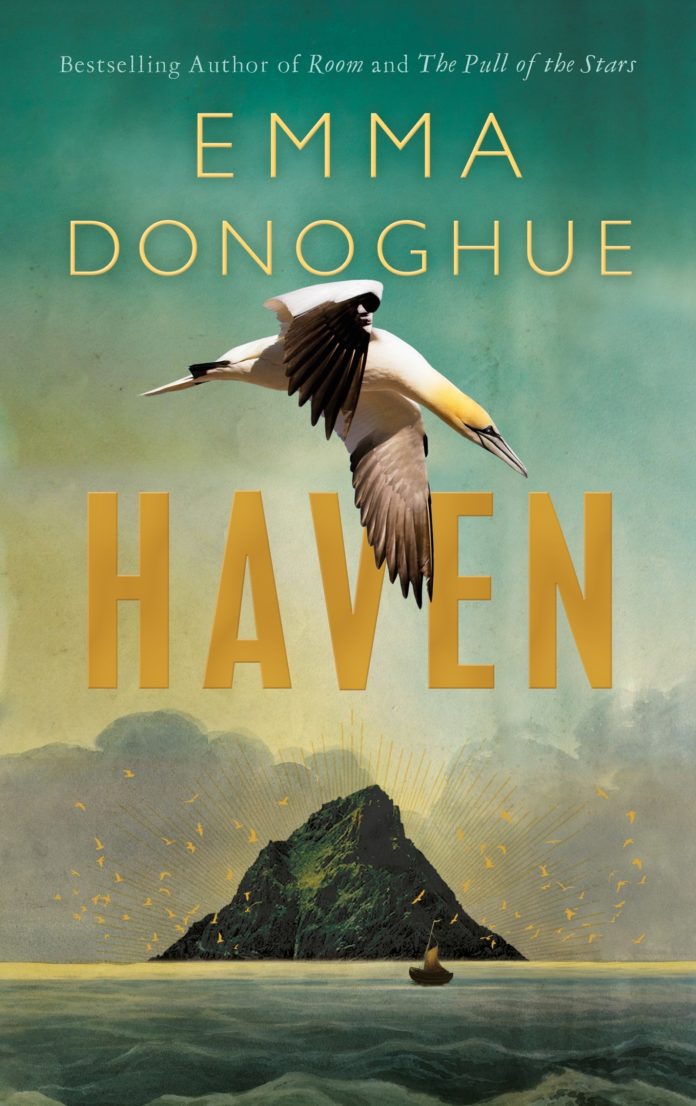

Haven by Emma Donoghue

Picador (Pan Macmillan)

Picture three men in a boat, laden with provisions, heading towards an island that one of them has seen in a dream. They carry with them a leather sail, crocks full of oats, a pouch of salt, fishhooks, a knife, a mallet for cracking stones, and seeds to plant for an imagined future. There is no room for spare clothes, for the comfort of a jar of honey, even for the bone pipe the youngest man plays. There is room, however, for vellum, holy water and blessed wafers, because these men are monks, in seventh-century Ireland.

Writer Emma Donoghue – whose earlier books include The Wonder, Astray, and Room – has created an entire world in this trio of men. Artt is the leader and visionary, driven to create a pure and holy place. Trian is not yet 20, always hungry, twitching with energy, desperate to be worthy. Cormac is an older man; he’d been a pagan, had a family who died in a plague; he’s an injured soldier, a convert and a man with a story for every occasion.

These three come upon a skellig: a stark rocky island with sheer cliffs and little water, honeycombed with puffin burrows, encircled by shearwaters and other birds, screeching with life. There, all the dramas of a community in miniature are played out: a fellowship of unequals, with a leader who’s a zealot and two followers working themselves to the bone.

Donoghue shifts between the fascinating day-to-day details of survival – the fire horn Cormac carries, to preserve embers; splitting rocks to make a dry wall; finding enough food – and the dynamics of the group. We need shelter, two of them say; no, we must build an altar, says the leader.

The tensions rise, the birds are slaughtered, and the weather is changing. An ostensibly tiny story into which so much can be read. KE

Marlo by Jay Carmichael

Scribe

Finding love was not easy in 50s Australia if you were a gay man. Christopher, the protagonist of Marlo, Jay Carmichael’s second novel, must break into the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria (simply referred to as the “Gardens”) at night to visit a known beat — which police might be staking out to entrap unsuspecting visitors, or where homophobic thugs might be waiting instead (sometimes they were one and the same).

Homosexuality was a criminal offence in Australia at this time, and as Carmichael explains in his epilogue, the 50s were a period of increasing hostility, stigma, surveillance and pathologisation of homosexuality, with people being convicted for what was called “unnatural offences”.

At the opening of the novel, Christopher has escaped the socially conservative coastal Gippsland town of Marlo for Melbourne to start a new life. But he discovers that even in a big city, life is constrained for those who don’t conform to heterosexual expectations. Despite not having a name for his urges, he lives in constant fear of being found out. Christopher desperately wants a private oasis where he can be free: “I could not protect myself in the outside world from the people who didn’t want me to exist in it.”

A chance encounter in the Gardens leads him to Morgan, an Aboriginal man with whom he bonds; but it’s an uneasy bond, as they can only show affection under the cover of night, and even a simple trip to the zoo attracts police attention. Christopher finds it hard to speak his mind and say what he wants, while Morgan is also dealing with the violence of racism.

In the epilogue, we’re reminded that homosexual relationships are largely absent from the historical record of the 50s, but Carmichael brings them movingly to the fore in this short, atmospheric novel. My only complaint is that Marlo left me wanting more. SL

Against Disappearance: Essays on Memory

Pantera Press

Dear reader, in recommending books to you, know that I only have 300 words to say whatever it is I wish to, and that part of me thinks maybe today I should just write the following three words 100 times: Read this book.

Against Disappearance comprises all 20 of the longlisted works from the 2021 Liminal and Pantera Press Non-Fiction Prize. There is a remarkable degree of shared imagery and overlapping concerns — especially around the right to maintain silence, to refuse. Pieces serendipitously connect to one another, and these connections make reading the book a pleasure, allowing the reader to wander, and to wonder, too, at how much might be made visible and how much concealed by the complexities of appearance, the violence of knowledge.

grace ugamay dulawan, describing the spectacle of colonisation and racism, writes about men who “took some of us on his arm to his country and put us not on a pedestal but our own arena in which we performed for a CAPTIVE audience […] I want to say I’m not EXQUISITE but merely human”. dulawan is describing what it means to just be – neither as miracle nor as tragedy, not a star nor a martyr, not a trauma or a spectacle but something more: something ordinary, something alive and real, something thoroughly unremarkable.

The final piece, by Frankey Chung-Kok-Lun, concludes the anthology on a painful but affirmative note, reminding us that no matter how much we have lost in the past few years – to COVID, to distance, to racism, to police violence, to intergenerational pain — we still have each other.

The endpapers, framed by a rectangle of black ink, invite the reader to consider what might be, or have been – and, perhaps, to contribute their own thoughts. As Anwen Crawford wrote, in a book which incorporated a similar visual motif, “No document can make you manifest.”

Hannah Wu writes in this volume, “The work of art becomes participatory, malleable; it constantly changes through the process of being encountered and passed on by others.” We see that manifested in how Against Disappearance, under the editorship of Leah Jing McIntosh and Adolfo Aranjuez – aided by Danny Silva Soberano, Adalya Nash Hussein, Cher Tan, Shakira Hussein, Maddee Clark and Brian Castro – invites the reader to laugh, to rage, and to fight.

So here’s the message I want you to pass on to you: Read. This. Book. DF

Every Version of You by Grace Chan

Affirm Press

Melbourne, 2080: Federation Square is gone – razed in American air strikes. The Yarra has dried up. But despite the soaring temperatures, tech fans are lining up outside a shop on La Trobe Street to be the first to get their hands on a “Neupod” – the latest development in immersive VR technology.

Tao-Yi and Navin are two of the people in that queue. Their heads are shaved (to improve the neural connection to the VR gear) and they have goggles and gloves to protect them from the pollution and heat. Back home, the Neupod will take them to the safer, cleaner digital world of Gaia, where they can work, shop, eat and party – all while appearing as the avatar of their choice.

As a speculative fiction novel, Every Version of You is cleverly done. The world Grace Chan has imagined, just two generations into the future, feels convincing and terrifying.

But it’s as a character study that this book really shines. Tao-Yi and Navin are several years into their relationship. She’s ambivalent about Gaia, and yearns for a deeper real-world connection to her depressive mother and her Chinese Malaysian heritage. Navin, on the other hand, is spending more and more time online. In the real world, he’s suffering from chronic health problems, but in Gaia, he is pain-free and able to live to his full potential.

When the opportunity arrives to fully “upload” to Gaia – leaving the real world behind altogether – it drives the couple even further apart.

Chan masterfully explores science and the notion of self in one of the most assured debut novels I’ve read in a long time. I highly recommend it. CN

Violent Phenomena: 21 Essays on Translation

Tilted Axis Press

Taking its title from an observation philosopher Frantz Fanon made in 1961 (“Decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon”), Violent Phenomena asks questions about the power dynamics involved in translation. Who translates? How do we translate? These questions require time, reflection, and self-interrogation.

Given the history of colonialism, the relationship we have to language is invariably complicated. As Cairo-born literary translator Nariman Youssef and researcher Gitanjali Patel write in Violent Phenomena, “many translators of colour do not have a ‘heritage language’, or may be estranged from it as a result of colonial legacies, conflict, or assimilation pressures”. In the same essay, they write:

“Colonial acquisition has its rules and conventions. What is brought over is made to fit into the predetermined spaces of labs, libraries and museums, its difference accentuated but its foreignness contained. These rules and conventions have been internalised by many in the West who are allowed to go through life with uncontested identities. Their curiosity about what lies beyond the realms of their own identities remains trapped within a scale of otherness: too foreign on one end, not foreign enough on the other. We see this in the exoticising sparkle around ‘discovering’ literature from places that have little representation in the anglophone literary sphere, as long as they contain the expected degree of foreignness; no more, no less.”

Karachi writer Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi offers a similar sentiment in her essay within this collection, writing that “the idea of ‘decolonising translation’ seems, potentially, an oxymoron. What will we talk about next? Decolonising Colonialism?”

The essays, selected by Dr Kavita Bhanot and Jeremy Tiang, cover a wide range of ideas, from Layla Benitez-James considering what happens when an “Oreo” – a Black person who “acts White” – encounters Proust, in Proust’s Oreo, through to Arab poet Mona Kareem questioning why the act of translation is so often heralded with saviour-complex language as a kind of “service for the Third World poet”, in Western Poets Kidnap Your Poems and Call Them Translations.

Formally inventive and thought-provoking, Violent Phenomena is timely and impressive. DF

Tune in to ABC RN at 10am Mondays for The Book Show and 10am Saturdays for The Bookshelf.