MILWAUKEE — It wasn’t easy for Don Schwamb to go to his first Gay Peoples Union meeting.

Today, Schwamb is the founder of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project and has spent decades advocating for the gay community in Milwaukee. But back on that day, in the early 1970s, he had to work up his courage to even walk in the door.

“I sat in my car and watched people go in and thought, ‘I don’t see any police cars. I don’t see any rumbles or anything, any fights. I’m going to risk it,’” Schwamb said.

For Schamb, like many others who found the nerve to show up to meetings, the decision was life-changing. In the midst of a world that didn’t accept LGBTQ+ people, the Gay Peoples Union, which was active in Milwaukee through the 1970s and early ‘80s, showed them that they weren’t alone — and that they even had power.

“It was as if somebody turned on a light in the midst of darkness,” said Miriam Ben-Shalom, a former GPU president. The group became “like a family,” said Michael Lisowski, who served as a former vice president.

GPU’s impacts on Milwaukee, as well as the broader gay rights movement, live on 50 years later, Schwamb said. From organizing protests and Pride parades to providing health care and putting out a newspaper, the group made its mark far and wide.

“I remember GPU as being the genesis of so much of what we know now,” Schwamb said. “It’s incredible, the effect GPU had on this city.”

* * *

The Gay Peoples Union got its start half a century ago as a spinoff of earlier groups at UW-Milwaukee, soon after the Stonewall riots brought national attention to the gay liberation movement.

Don Schwamb, a GPU member and founder of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project. (Maddie Burakoff/Spectrum News 1)

Eldon Murray — who would grow to be recognized as a leading activist in the national fight for gay rights — was one of the founders of GPU. He and Alyn Hess, a fellow Milwaukee activist, came together to kick off the group in 1971, frustrated with the lack of real action for gay liberation in the area.

“When I look around me, I see those less fortunate who have suffered miseries and cruelties that are traceable only to man’s inhumanity toward his fellow man, and in particular, toward others whose sexual orientation is different,” he said at a 1972 GPU meeting, according to archival records. “I had always wanted to do something to alleviate the injustices I saw.”

For some of the members, GPU was one of the first places they could find a community. After all, it was still a time when, as Schwamb put it, “You couldn’t be gay, period.”

“We were all afraid of being — if not arrested, losing our jobs, at least,” he said.

In Milwaukee, police would regularly raid known gay bars, said former member Mark Behar, finding any reason to shut down business or hand out tickets. Attacks on bars sparked the riots at Stonewall — and Milwaukee’s own early uprising years before, at the Black Nite brawl — both of which were important in sparking more LGBTQ activism.

And on top of the harassment people faced, homosexuality was still criminalized in the state, meaning there were real legal threats for gay Wisconsinites.

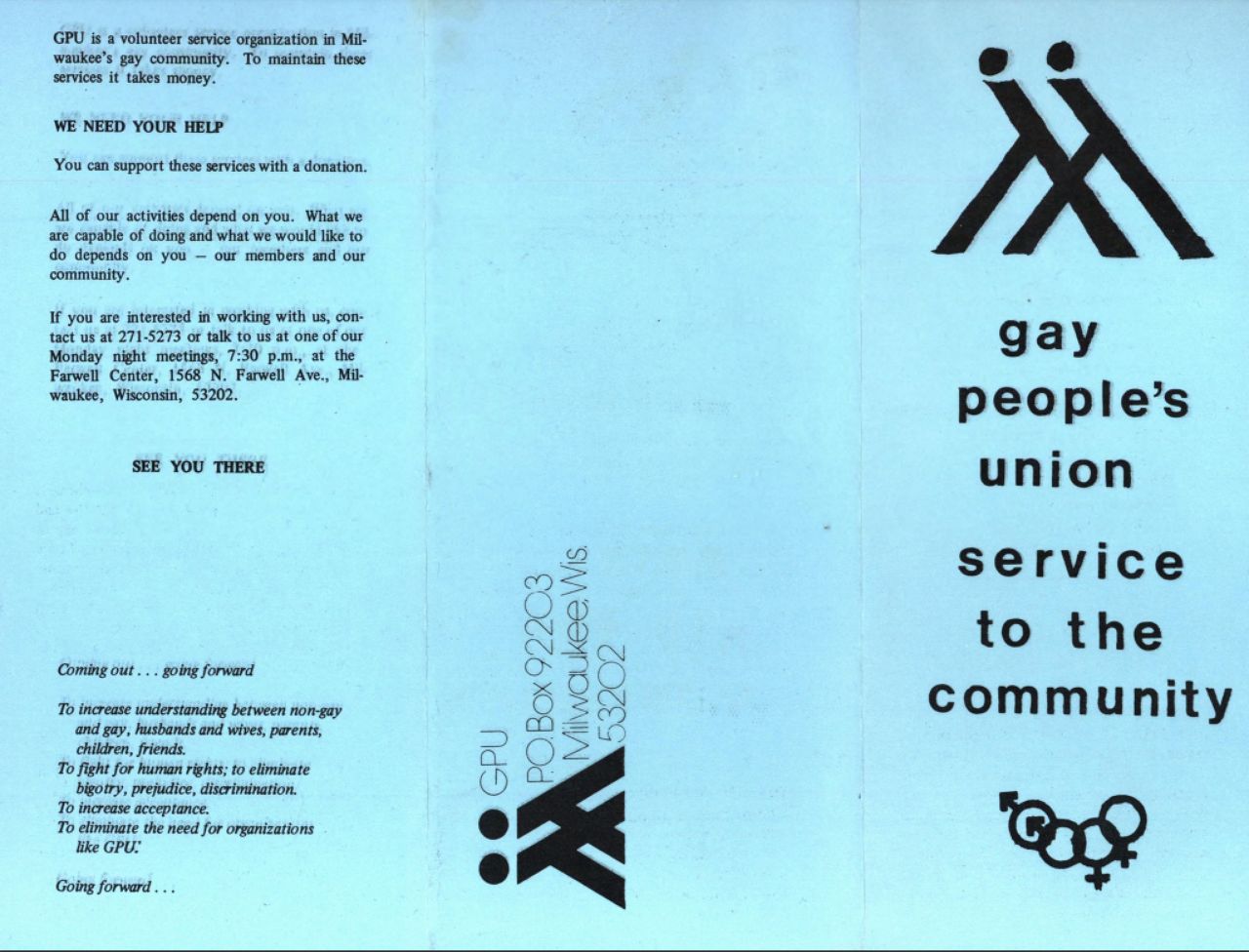

A GPU brochure. The logo comes from the Greek letter gamma, which was a symbol for gay people at the time. (From the Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries)

Plus, the cultural conversation around LGBTQ+ people was full of negative stereotypes, explained former member Bill Meunier. The common knowledge, as he put it, was that “gays are very unhappy. They don’t have love in their life.”

After working up the nerve to go to a GPU meeting, though, Meunier realized all that conventional wisdom was wrong. He saw same-sex couples being happy together; he found a group of people like him, who were trying to help their community.

“It was like I had a 20-year pain that was suddenly gone,” he said. “I realized that I wasn’t alone.”

The meetings would often feature speakers and discussions on different topics, “always aimed at raising personal liberation as well as group liberation,” as Ben-Shalom wrote in a 1975 report.

They were also just a place for people to be together, and be themselves, in a society that didn’t offer many chances to do so without fear.

“It was wonderfully liberating just to go and see people who were at least unashamedly gay or lesbian in one place,” Behar said.

* * *

The work of the Gay Peoples Union went way beyond meetings, though. Over the course of the 1970s and early ‘80s, the group undertook a huge range of projects across the city.

“It was like a river,” Meunier said. “With offshoots flowing in their own directions, in their own ways.”

One of GPU’s first projects was a hotline “for those just becoming aware of their gay identity.” Meunier said the line, staffed by GPU members, served as a lifeline for a lot of people — whether they were getting thrown out of their homes, fired from their jobs, or just needed “someone to talk to, someone to say they are afraid.”

Mark Behar, a GPU member who worked with the group’s venereal disease clinic. (Maddie Burakoff/Spectrum News 1)

In 1975 alone, the hotline answered more than 8,600 calls, according to the group’s annual report that year.

GPU was a pioneer in the media world, too: The group headed up a radio show, “Gay Perspective,” and a nationally distributed newspaper, “GPU News” — which were some of the first publications in their fields to focus on gay life.

In 1974, the group founded a venereal disease center to help keep the community healthy, and especially combat the epidemic of syphilis and gonorrhea going around at the time, said Behar, who was involved with running the clinic during his years with GPU.

The clinic started off by offering free testing with the support of the Milwaukee Health Department, Behar said. It would later start treating patients as well, and helped lead the way for testing and outreach when the HIV/AIDS crisis swept through the country.

Today, the center — after a relocation — is still running, as the Brady East STD Clinic.

The list goes on. After the church where they held some of their early meetings burned down, GPU moved to a new spot on Farwell Avenue, kicking off the first gay and lesbian community center in the city. After a raid on a local bath house, GPU started a legal defense fund to help bail people out and get them legal representation.

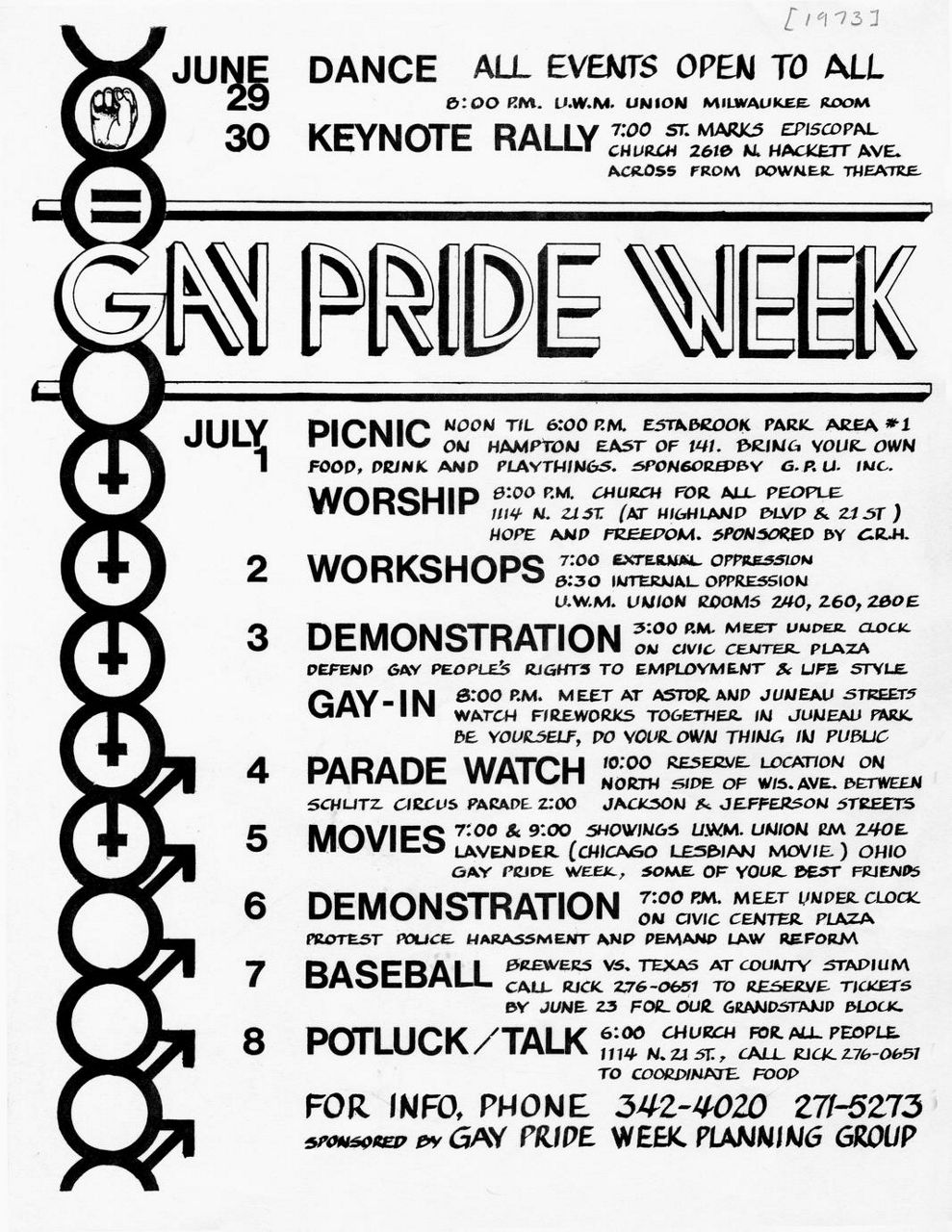

The group also organized the city’s first Pride event — a far cry from today’s PrideFest, but still a way to stand up for the community, said Meunier, who led the organizing committee.

Michael Lisowski, former GPU vice president. (Maddie Burakoff/Spectrum News 1)

In a lot of these activities, GPU was “way ahead of the curve,” said historian Michail Takach, a curator on the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project. The group pushed Milwaukee on par with other cities, like New York and San Francisco, that were paving the way for gay rights, he said — and that legacy is still felt in the city.

“Almost every LGBT organization, or LGBT health organization, that exists in Milwaukee today can trace its roots back to GPU,” Takach said.

* * *

The stigma and paranoia around coming out — and Milwaukee’s vibe as a “don’t push it too far” type of community — proved to be a challenge for activism, Lisowski said.

“Although people were interested in hearing about it, few people, I think, were interested in direct action,” Behar added. “It was a very politically conservative community, as it is today.”

Throughout GPU’s lifetime, the group faced some tension over whether to focus more on providing services to the community, or pushing for change through protest and direct action, Behar said.

In his 1975 report as chairman of the board, Hess wrote that GPU should be more politically active. He raised concerns that their members didn’t seem willing to “set the time aside to become sufficiently interested in Gay Liberation (as a movement for their own good)” — to “think about it all the time and do something about it every week.”

Even the concept of a Pride parade that would call attention to LGBTQ+ people made some members nervous, Meunier recalled.

A Gay Pride Week flyer from 1973. (From the Archives Department, UW-Milwaukee Libraries)

They had reason to be worried about backlash. In fact, the police derailed the first-ever event a bit by raiding all of the local gay bars the night before, he said. Still, Meunier thought that living in shame and fear was doing more damage than putting themselves out there.

“By not having a Pride parade, by not standing up for ourselves, we’re hurting ourselves,” Meunier said. “To be afraid of what someone else is going to do to you, and then to do it to yourself, that never made any sense to me.”

Despite the danger, GPU members did become active in protests and political organizing. They marched in the streets of Milwaukee and in Washington, D.C.; they testified before the state legislature; they campaigned for candidates who were progressive on LGBTQ+ rights.

For Ben-Shalom, the group also empowered her to fight her own battle as an activist. After being dismissed from the U.S. Army Reserves for identifying herself as a lesbian, she went on to fight a years-long legal battle challenging the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

Though she could have lied about her sexuality to keep her position, Ben-Shalom said GPU had taught her that she shouldn’t accept oppression from anyone.

“I don’t think I should ever have had to lie about who and what I am,” she said. “Because I’m capable of loving another human being is not something that’s negative.”

Si Smits, a former GPU treasurer. (Maddie Burakoff/Spectrum News 1)

* * *

Today, the GPU still technically exists as an active nonprofit — “because I file those papers,” said Si Smits, who served as GPU treasurer for a time. But the group mostly faded out after the early ‘80s.

Why did the group get less active? For one, “gay liberation succeeded in doing its purpose,” Smits said.

In 1982, Wisconsin passed the nation’s first gay rights law, protecting LGBTQ+ residents from discrimination in employment and housing. The following year, Gov. Tony Earl established a statewide council on lesbian and gay issues.

Behar, who served on the governor’s council, said this time period saw the conversations that were kickstarted by GPU now getting adopted into the state’s politics.

It was “no accident” that the state was leading the way on gay rights in the ‘80s, Takach said — it was because through GPU, “everyday people just stood up and made things happen, and they changed Wisconsin.”

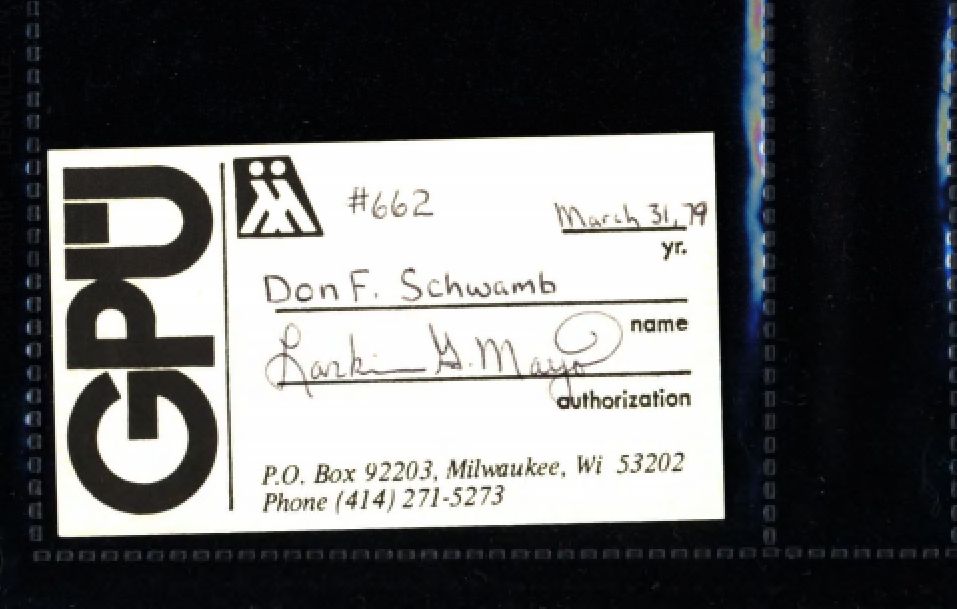

GPU membership card for Don Schwamb. (From the Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries)

Other factors were at play in GPU’s decline. The growth of the internet meant LGBTQ+ people didn’t need groups like GPU to find community, Behar said.

And the AIDS epidemic also tore through the community around this time, leading many people to either get sick or stay home out of fear. Hess, one of GPU’s founding members, passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1989.

These days, Meunier said he sometimes wishes that groups like GPU were still around and “could get back into the fight.” Despite the huge strides made since the 1970s, there is still work to be done on LGBTQ+ rights in this country, he said.

Takach feels like his generation has been the first to really benefit from “the blood sweat and tears of the Stonewall generation” — a generation that included GPU. But after that era wound down, he said he hasn’t seen many groups pick up the torch or recognize the history that paved the way for them.

“I think what happened was, people forgot. They forgot how hard they used to have it. They forgot what life was like before the ‘70s and gay liberation,” Takach said. “They just got so used to these freedoms that they forgot how hard it was to win them — and how easily they can be taken away again.”

Along with Schwamb and the LGBTQ History Project, Takach hopes to keep sharing that hidden heritage and help people recognize the legacy of gay rights pioneers.

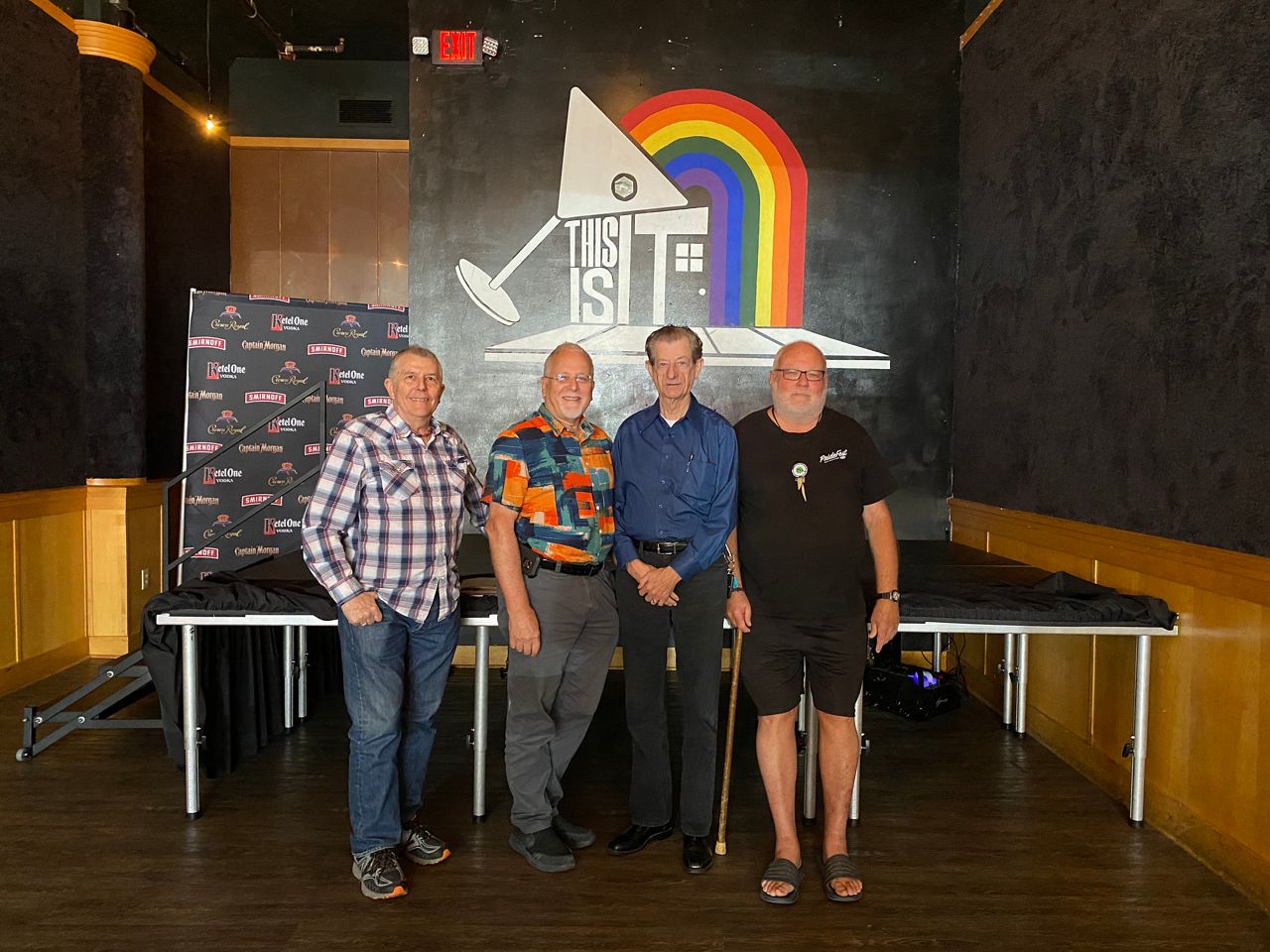

GPU members reunited at This Is It! bar in Milwaukee. (Maddie Burakoff/Spectrum News 1)

Of course, the history lives on not just in GPU’s impacts across Milwaukee, but in the members who grew up and came out within the group. For a lot of members, Lisowski said, GPU was like a family — one that shaped them into the people they are today.

“The role of the family is to get you ready to go out into the world. And GPU was like our nuclear gay family at the time,” Lisowski said. “We learned from each other. We had more experiences and skills. Some of us got more courageous. And from there, we just kind of spread out, like you would from a family.”