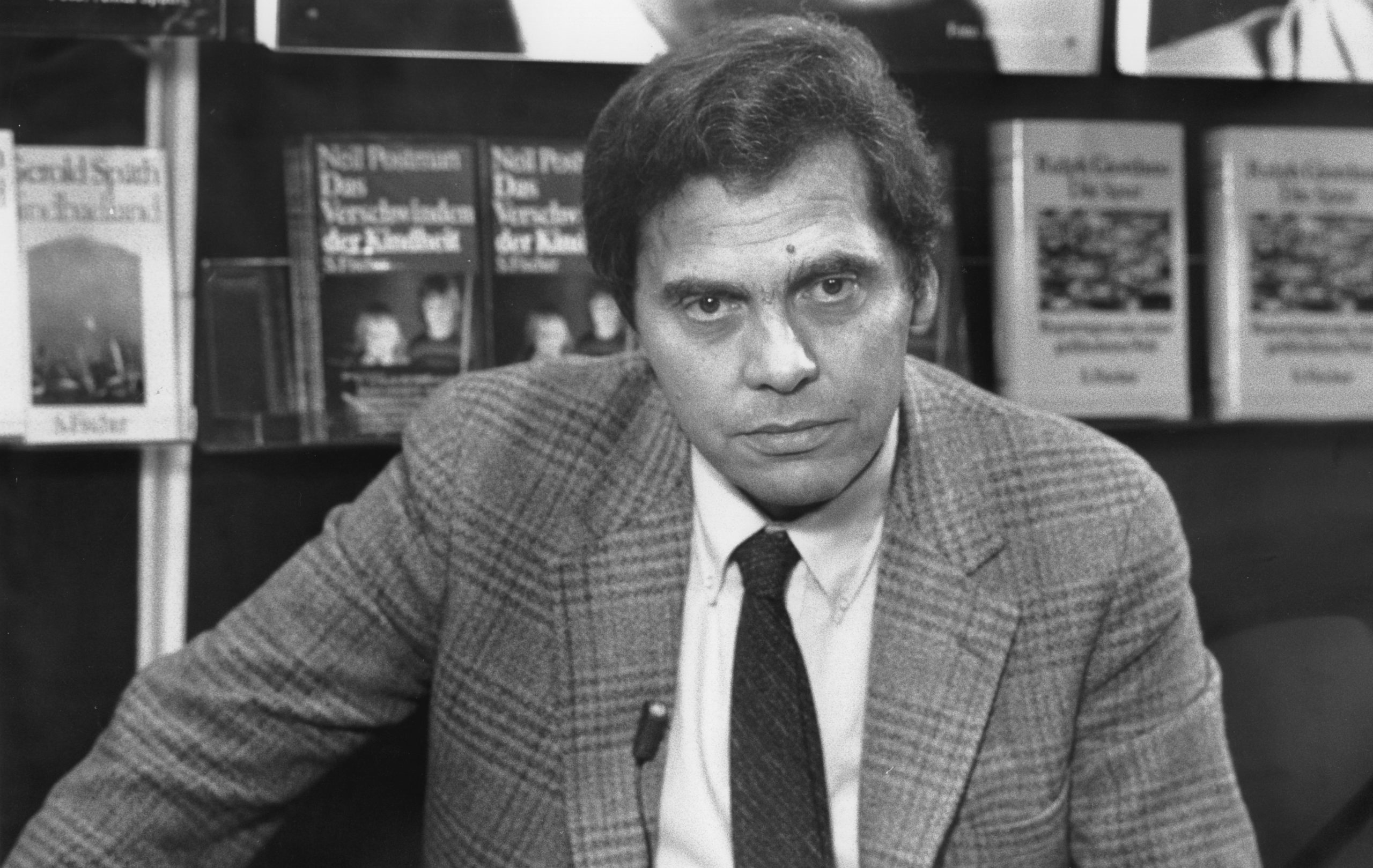

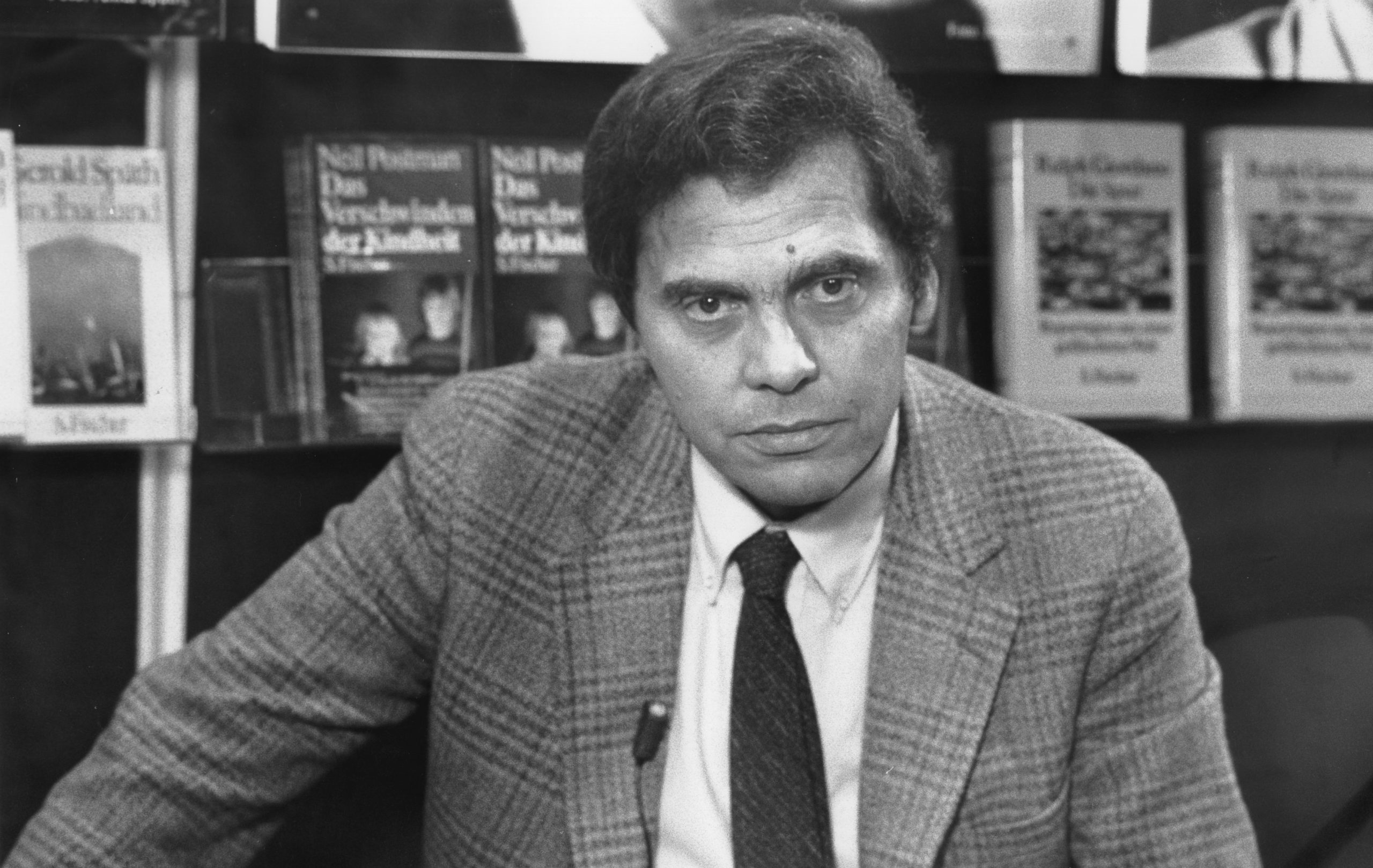

In 1992, NYU professor Neil Postman wrote that the “uneasy tension” that once existed between “the technological and the traditional” was no more. The United States, he explained, had become a “technopoly.” According to Postman, this triumph of technology does not make the traditional worldview “illegal…immoral” or “even…unpopular,” but rather “invisible and therefore irrelevant.

“It does so,” he added, “by redefining what we mean by religion, by art, by family, by politics, by history, by truth… so that our definitions fit new requirements.”

Thirty years later, Postman’s vision of a “totalitarian technocracy” that maintains power by altering how people perceive reality seems more prescient than ever. But what of the “fundamentalists” that resist? Postman described such people as “neither Luddites nor primitives,” explaining that they are not “ignorant of nor indifferent to the benefits of science and technology,” but rather “wounded” by “the assault that science made on the ancient story from which their sense of moral order sprang.”

Are these wounds fatal? Is there any hope for a recovery? Postman couldn’t possibly have answered these questions, but last November in Hyattsville, Maryland, roughly 30 socially conservative, Christian families, troubled by the “omnipresence of technology in the modern world” and inspired by the late NYU professor’s work, committed to what they call “the Postman Pledge.” It reads as follows:

As Christian parents, we recognize that everything God created is good and that we have the great privilege of teaching our children to know, love, and serve Him in the good world He created. We also recognize that technological developments in the culture undermine our capacity to inhabit the world and engage in social life as richly or fully as we ought. Therefore, we pledge for the next year not to allow our children to have smartphones or use social media. We also pledge to conscientiously limit our family’s use of electronic technologies in general and to cultivate the habits of attention and presence that allow us to grow in love of one another and of God. Knowing that we were created for deep bonds of community, we pledge, finally, to foster friendships among our families in the natural, traditional ways human cultures have always done.

One year after its conception, parents report that the effects of the simple pledge have been profound. Today their children’s “attention and focus,” ability “to be intentional,” and love for “what’s good, what really nourishes and satisfies,” as one put it, have all improved significantly.

Jeanne Schindler, a political philosophy professor turned homemaker who founded the group, attributes the Postman Pledge’s success in part to the realization that the real enemy is not technology itself so much as a technological culture that “reduces everything to an instrument,” making life “flat and trivial.”

As Postman wrote in his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: “Liberation cannot be accomplished by turning [television] off. Television is for most people the most attractive thing going any time of the day or night… If we don’t get a message through the tube, we get it through other people”

The answer to this technological “colonization of our consciousness,” then, cannot simply be to ban children from cell phones and social media. Doing so without providing some other form of community risks leaving children feeling “idiosyncratic and isolated,” Schindler said. For that reason, while the Postman Pledge begins with a commitment to limit tech usage, it also aspires to promote friendships grounded in “the rhythms of the real world.”

For the past year, Scottish dances, field days, and community picnics have served this purpose. Niki Flanders, whose family helps lead the singing and dancing, explained that these events are important because “they draw us outside of ourselves, and in order to grasp reality, we must see beyond the material world.”

Doing so helps develop the “traits of character and ways of living essential to discipleship,” Schindler said. Overall, by cultivating a “certain disposition to living in the world in a way that is attentive and present,” Postman Pledge parents hope that these events will help their children be less “inclined to become dependent upon technology” in the future.

“I know we can’t go back to 1988 in terms of technology,” explained Will Bertain, a father of eight who serves as an assistant headmaster at the St. Jerome Institute, a Catholic high school in Northeast D.C. “But I’ve had to overcome damage from my own use of technology, and having learned those things… I want to intentionally craft a home and provide my kids those fundamental human experiences.”

Subscribe Today

Get weekly emails in your inbox

Only time will tell whether the Postman Pledge will be successful. But the stakes couldn’t be higher. Upstream of abortion, gay marriage, transgenderism, and every other contemporary culture war issue sits technology, and if conservatives don’t confront it squarely, then our age of disembodiment will only drag on.

So, while policymakers continue to argue about how to govern digital spaces, efforts like the Postman Pledge shouldn’t be overlooked. After forming in fits and starts for years, such associations, which, as Tocqueville makes clear, have always been essential to conserving virtue in America’s body politic, are now taking on a more formal character. And today, they may be the country’s best bet to stop conceding more and more of childhood to the digital world and start recovering the reality conservatives have been counting on for so long now.

On such a quest, Neil Postman may seem like a peculiar guide. But it is precisely this peculiarity that could make his message accessible to a new generation of parents. Indeed, in the long run, not hailing from any particular church or party may prove advantageous for Postman’s legacy, a bellwether for all people concerned about technology to rally around.