:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/XW4JOGACYVE5ZCAANJLKAQEEVA.jpg)

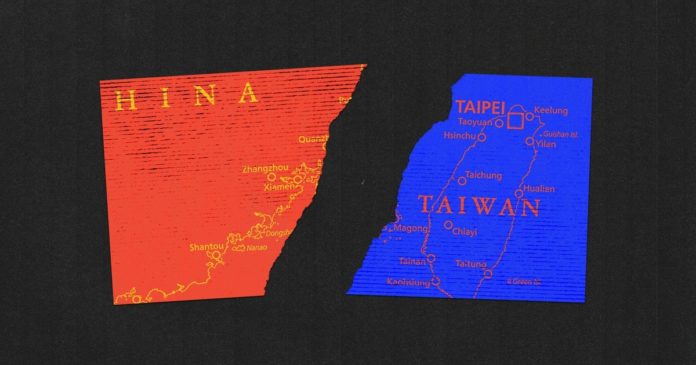

An “unstoppable trend.” A “shared aspiration of all the sons and daughters of the Chinese nation.” That’s how the Chinese Communist Party described its goal of “reuniting” with Taiwan in the weeks following House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s (D-Calif.) August visit to the island.

The rhetoric came with the added punch of unprecedented Chinese military exercises, but it’s nothing new. Chinese leaders have hammered home that message for decades, maintaining that Taiwan is part of “One China” and that people on both sides of the strait yearn to be “reunited.”

But increasingly, people on the Taiwanese side don’t feel that way at all. Under President Tsai Ing-wen, Taiwan has essentially existed as an independent state, without declaring as much for fear of stoking China’s anger. And fewer and fewer people in Taiwan back “reunification” with the mainland. Only 6.5 percent of Taiwanese people say they support unification at some point, according to a recent poll conducted by the National Chengchi University in Taipei. Meanwhile, more than 30 percent are in favor of moving toward independence — up from just 15 percent in 2018.

“If you look at the change in the past two decades, it is very clear that there is already a consensus in Taiwan of ‘anti-unification,’” Fang-Yu Chen, an assistant professor of political science at Soochow University in Taiwan, told Grid.

ADVERTISEMENT

Grid analyzed public opinion surveys and spoke to people in Taiwan to better understand the evolution of Taiwanese views involving identity, democracy and social issues. What we uncovered is a strong current of anti-China sentiment, along with a growing sense of an independent Taiwanese identity. As China cranks up the pressure on Taiwan, these trends suggest that the regime in Beijing is fighting against a powerful tide. Many Taiwanese citizens feel that political and social reforms in Taiwan have pushed the two states further apart, and they are also worried — rather than enthusiastic — about what a mainland takeover might mean for them.

An independent identity

Decades ago, many Taiwanese people thought of themselves first and foremost as Chinese. But over the years, that has shifted significantly. Ask a resident of Taiwan today about mainland China — especially someone under 30 — and you are likely to find a lot of people firmly opposed to being identified with China in any way. Although Taiwan’s official name is still “the Republic of China,” several recent studies have shown that a growing percentage of Taiwanese people now see themselves as solely Taiwanese. As of June, 64 percent of people reported identifying as Taiwanese, while the percentage of people who consider themselves both Taiwanese and Chinese fell to 30 percent, according to the Chengchi University survey.

A sense of distinct identity is even stronger among younger citizens. Research from Pew has found that among 18- to 29-year-olds in Taiwan, 83 percent consider themselves solely Taiwanese. It’s likely that number is actually higher; the Pew survey was conducted in 2020, and tensions and animosity toward China have only risen since then.

That has left people like Henry Chang in the minority. An auto parts salesman born and raised in Taipei to parents who left the mainland after the Chinese Civil War in 1949, Chang told Grid he considers himself both Chinese and Taiwanese — and given his own history, that stands to reason; his parents were born on the mainland, and he has lived his entire life on Taiwan. But he recognizes that his dual allegiance is increasingly uncommon. “Young people’s relationships to China are increasingly weak,” he said.

Chang believes that’s due to media influence and a steady decrease in China-related curricula in Taiwanese schools. The surveys suggest many Taiwanese genuinely prefer the circumstances of their lives thanks to political and social reforms, or are tired of what they see as a growing militancy from the mainland. Or both.

ADVERTISEMENT

Political divisions: “We’ve gotten used to democracy”

For Taiwanese today, opposition to “reunification” with China is driven less by questions of identity — and more by politics and current events.

China has long pledged that Taiwan should be governed under a “One Country, Two Systems” approach, similar to the mainland’s official stance on Hong Kong. During the early 1980s, when Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) were both authoritarian states on what looked like a liberalizing track, unification — the ultimate outcome of the “one country” principle — seemed more plausible. More Taiwanese felt the strong tie to the mainland that Chang still feels — and political and ideological divides were nothing like what they are today. But Taiwan raced down that liberal track and emerged from the shadow of authoritarianism in the 1990s. Democracy has become deeply rooted on the island, while over the same period, mainland China has headed in the other direction. The likelihood of political liberalization in the PRC today appears almost nonexistent.

In the 2014 Asian Barometer Survey, results showed that Taiwanese held a largely utilitarian attitude toward democracy, seeing it as useful so long as it facilitated economic development. Chang, who says he votes “99 percent” of the time for the more pro-mainland KMT party, still maintains this view: “Democracy is very good,” he said, “but I think only on the precondition that everyone can live in peace and contentment, with good jobs, a stable family and enough food to eat.” His complaint is that of late, Taiwan has not regularly delivered those core economic rewards.

Nonetheless, that same survey found that 88 percent supported the idea that democracy is the best form of government, whatever its problems. That rate has gone up with the rise of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party, which has championed closer political alignment with the U.S. and a more confrontational approach to China. That survey finding stands in stark contrast with the mainland view — or at least the view of the government in Beijing. (The PRC defines itself as a “people’s democratic dictatorship” — “democratic” in the sense that the party’s self-proclaimed mandate is to govern according to the wishes of the people.)

Soochow University’s Chen told Grid that the democratic shift in Taiwan has made “reunification” harder to imagine. “We’ve had elections every four years since democratization, and we have local elections every two years, just like the U.S. So we’ve gotten used to democracy, and that is normal life.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Liberal values — and a generational divide

Along with a democratic process, Taiwan has embraced social reforms in recent years that have further deepened the contrast with China. Those reforms have been particularly popular among Taiwan’s younger citizens — and that in turn has been one more driver of a shift away from the mainland.

“President Tsai’s formula to win widespread support from the youth generation is not simply political in nature, but also rooted in promotion of liberal and progressive values that attract loyal followers,” wrote Min-Hua Huang, a professor of political science at National Taiwan University, in a recent analysis of the Asian Barometer Surveys. Huang said the surveys, taken from 2001 to 2018, show “that the youth generation is always more liberal than other generations by a significant margin, and more importantly, Taiwanese society as a whole continuously exhibits such an upward trend for the past two decades.”

Perhaps most notable among Taiwan’s recent liberal shifts was the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2019 — a first for any Asian government. A survey taken on the three-year anniversary of the legalization showed an increase in support for same-sex marriage, as well as broad support for gender equality and expression. Chen told Grid that “certain events like the legalization of same-sex marriage make Taiwan more proud of itself,” especially because the watershed moment led to widespread positive global media coverage of Taiwan.

The gay rights trajectory has been different in mainland China. Homosexuality was illegal in China until the late 1990s. A 2020 study found that “Chinese LGBT groups consistently experience discrimination in various aspects of their daily lives.” Under President Xi Jinping’s rule, there have been significant crackdowns on media depictions of gay characters and themes, and educational policies have been introduced with a view to shaping a more conservative and conformist Chinese social system.

More broadly, social life and civil rights are fundamentally different in the two societies. Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2022 report rated Taiwan 94 (out of a high score of 100); the island drew high marks across a range of political rights and civil liberties. By contrast, the U.S. clocked in at 83, and China a bleak nine. Under the category of “Freedom of Expression and Belief,” Taiwan achieved a perfect score of 100, with the report describing Taiwan as a country where “the news media are generally free, reflecting a diversity of views and reporting aggressively on government policies, though many outlets display strong party affiliation in their coverage … [and] personal expression and private discussion are largely free of improper restrictions.” China is of course infamous for its extreme censorship regime.

These differences matter to people in Taiwan. When asked why she opposes “reunification” with China, Amang Hung, a Taiwanese poet, told Grid, “the mainland suppresses freedom of thought and freedom of speech, does not respect life, and does not allow diverse values.”

What’s to come: “The trend is not reversible”

Cultural and geographic ties mean that China and Taiwan will likely remain connected in many ways despite the growing turbulence and these broad differences in opinion.

Yet recent trends suggest that as time passes and the younger generation takes the helm, a more strident sense of Taiwanese identity will become the norm. And that suggests that support for “reunification” will continue to fall. “The trend is not reversible,” said Chen, “but China is doing as much as it can to deter Taiwan’s independence.”

That deterrence now includes economic sanctions, frequent harsh rhetoric, and more regular military exercises in and around the Taiwan Strait. China’s crackdown on some forms of expression in Hong Kong has chastened many Taiwanese — and Beijing has tried to reassure residents of the island that they have nothing to fear. A recently released PRC white paper on Taiwan says that “Taiwan’s social system and its way of life will be fully respected, and the private property, religious beliefs, and lawful rights and interests of the people in Taiwan will be fully protected.”

Surveys and interviews suggest many Taiwanese don’t trust those pledges. “China broke its promise to Hong Kong to maintain [independent] political order for 50 years, failing in 23 years,” Chen said. “That shocked a lot of Taiwanese people because Taiwan is highly connected to Hong Kong.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The war in Ukraine has also been an eye-opener for many in Taiwan — for a different reason. The conflict — different in many ways, but also involving a major power moving against a much smaller population — has raised concerns about the island’s self-defense. A recent poll found that 74 percent of respondents said they would be willing to fight to defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion.

Above all, for many people in Taiwan, living under the shadow of near-constant tensions with China has led to a growing weariness.

Amang, the Taiwanese poet, told Grid, “I’m Taiwanese. In my next life, I hope I won’t have to make a choice. That is a truly free person.”

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.