Kimberly Shappley has described herself as an Alabama-born army brat. She was raised in the South on the Mississippi land of her great-grandparents, and, as an adult, she became an ordained evangelical minister and grew roots in conservative Brazoria County, Texas. She is also the mother of an 11-year-old transgender daughter, Kai.

“Things changed for me when I overheard Kai praying for Jesus to take her home to be with him forever,” Shappley said in 2019 testimony to Congress as Kai sat behind her, drawing with colored pencils like a typical kid. “At first, I thought nobody had to know Kai was transgender … But that could not remain a secret in a small town.”

Shappley described Kai being locked out of restrooms and having accidents in front of her schoolmates, being deadnamed — or called by the birth name she no longer uses — by her teachers, and being bullied without intervention from the adults in her school.

Kai and her mother felt pushed out of the district — where the superintendent compared transgender people to pedophiles and polygamists in a statement to a local paper — and they relocated to Austin. There, things changed: Kai was invited for sleepovers, free to use the bathroom she identified with, and noted by her teachers and principal as highly intelligent.

Then, in 2022 the environment once again turned hostile when Texas Gov. Greg Abbott issued an order requiring licensed professionals — including teachers and nurses — to report parents of transgender students receiving gender-affirming healthcare as child abusers. This time, and after years of resistance as a vocal LGBTQ activist, Kai and her family moved out of state.

As an increasing number of states follow suit with anti-LGBTQ policies, schools have become a battleground for opposing political and religious ideologies. Caught in the crossfire and sometimes on the frontlines are LGBTQ students themselves, alongside the families, teachers, principals and counselors who care for them.

Kimberly Shappley, @EqualityTexas Faith Outreach Coordinator and mother of a transgender daughter, testifies before a Congressional hearing on the #EqualityAct. #HR5 pic.twitter.com/Bm6xpRwkUv

— Human Rights Campaign (@HRC) April 9, 2019

Bruce Winick remembers tensions running high in the Dade County Courthouse Commission chambers. Boos and cheers echoed from the overflow crowds that spilled into the hallways. Pending before the Board of Commissioners of Dade County was an ordinance that Winick, who at the time was general counsel of the state’s American Civil Liberties Union chapter, had drafted to protect lesbian and gay individuals in housing, public accommodation and employment.

Attendees of the highly controversial meeting waved placards that read, “God Says No. Who Are You to Be Different?” and “Protect Our Children, Don’t Legislate Immorality for Dade County.”

It was 1977.

In his testimony, Winick said gay men and women “are unnecessarily harassed by the lack of basic civil rights,” and some “struggle to cope with the effects of such discrimination.”

The lesbian and gay protections passed, but from the resistance was born “Save Our Children,” the first national anti-gay group, which later succeeded in getting the ordinance repealed.

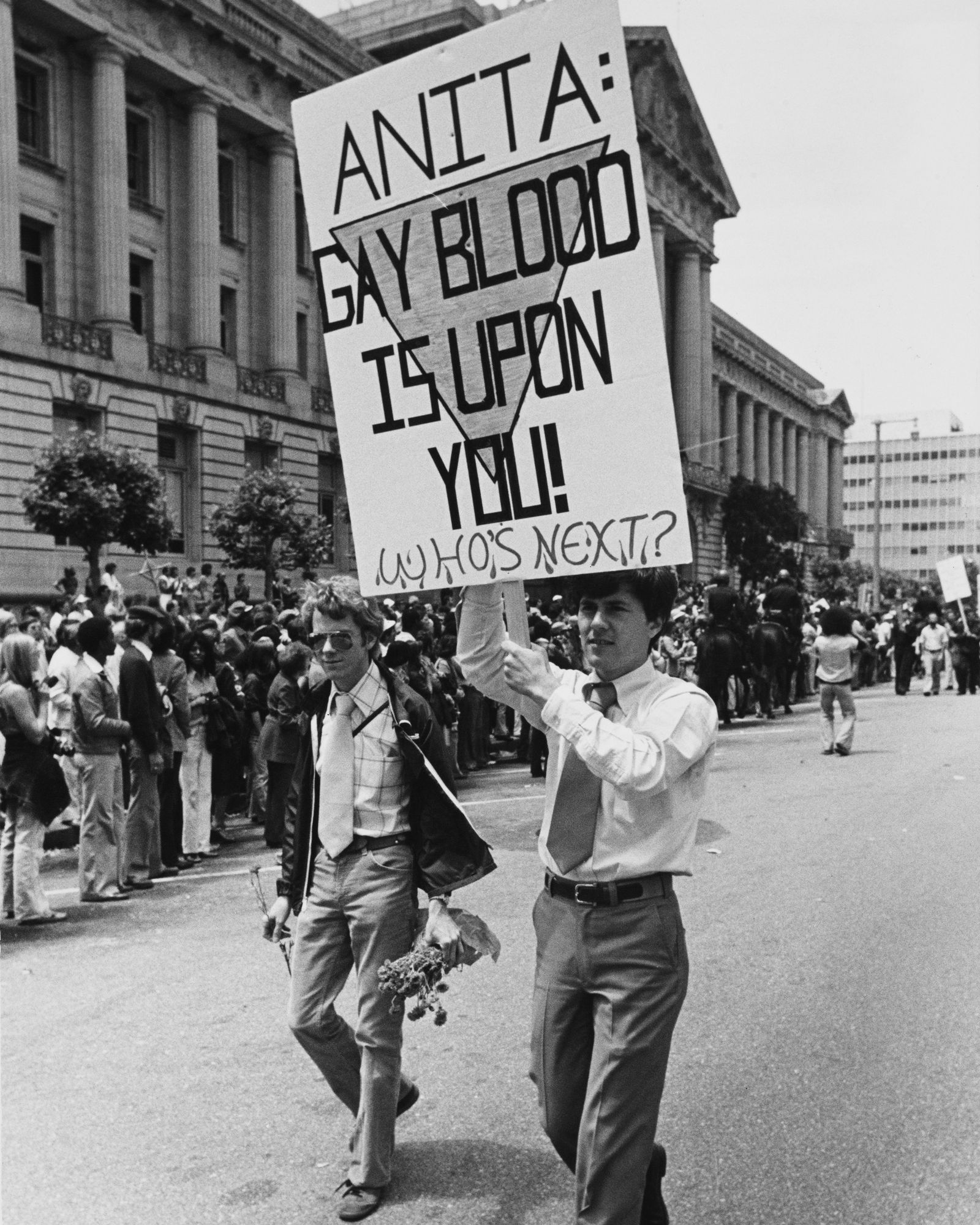

Singer Anita Bryant spearheaded anti-gay efforts, including a push to “Save Our Children,” and sparked protests like this one in San Francisco on June 26, 1977.

Archive Photos via Getty Images

Anita Bryant, singer and lead anti-LGBTQ activist who founded the movement, feared it would “allow homosexuals to teach my children.” On the other side of the nation, Bryant’s organization inspired Republican state Sen. John Briggs from California to advocate for the firing of any teacher who was gay or supported gay rights. The measure, which made it to the ballot, eventually failed.

Nearly half a century later, and in a case of déjà vu for education and LGBTQ experts, a wave of anti-LGBTQ policies and rhetoric is spreading nationwide. Much of the focus still centers around schools.

In 2022, lawmakers in 23 states have introduced — and 13 states have passed — anti-LGBTQ bills, according to the Human Rights Campaign. The measures range from banning gender-affirming healthcare and prohibiting gender and sexuality-related discussion in classrooms to limiting transgender students’ access to facilities and athletic teams.

Since Florida’s introduction and passage earlier this year of the Parental Rights in Education law, known by detractors as “Don’t Say Gay,” multiple states have jumped on the bandwagon. The Florida law gained national attention for limiting teachers from discussing gender identity and sexual orientation in their classrooms.

Even in states that haven’t passed anti-LGBTQ legislation impacting students, Republican leaders are providing momentum to put local policies in place to accomplish the same thing. In Virginia, for example, Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin pushed districts in September to require parental approval for teachers and staff to use different pronouns or names for students, and to limit students’ participation in athletics and access to bathrooms to those aligning with their sex assigned at birth.

The overall arguments for and against LGBTQ rights in schools have not changed in half-a-century from what Winick and Bryant espoused back in the 1970s. On one side, LGBTQ advocates say marginalized groups deserve civil rights protections and mental health access. On the other are activists who say LGBTQ inclusivity and representation indoctrinates their children into a culture opposed to their religious and political values.

“I think that children are a group of people that is easy for politicians, religious leaders, [and] people in charge to use to frighten the population,” said Michael Bronski, Harvard professor of the practice in media and activism in Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Bronski’s research interests include LGBT history and culture.

This is why schools historically have become, and are still today, the battleground in society’s fight for and against LGBTQ civil rights, Bronski said. “There’s nothing worse than harming children.”

California state Sen. John Briggs debates Proposition 6, which he authored to provide “a system for determining fitness of school employees engaged in activities related to homosexuality.”

Courtesy of PBS SoCal via American Archive of Public Broadcasting and Digital Commonwealth

‘I feel like constantly targeted prey’

But LGBTQ youth are being scarred in the process.

“I feel like I was forced into an exhausting position of constantly having to advocate for myself and other queer students when I just want to enjoy being a regular high schooler,” said Olivia, an LGBTQ student and member of GLSEN’s National Student Council. She describes being harassed, unable to focus on assignments or explore her identity and interests, and always being on edge and apprehensive in school.

“I feel like constantly targeted prey,” she said. GLSEN has asked that Olivia’s last name not be used since she is a minor.

And it’s not just older students who shoulder this burden. Transgender elementary school students often feel as if they carry the responsibility on their backs to educate others about LGBTQ issues, said Darrell Sampson, executive director of student support teams in Virginia’s Alexandria City Public Schools. Sampson conducts research focused on transgender students’ qualitative experiences.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, LGBTQ youth consistently show high rates of mental health challenges and suicide risk.

According to a 2022 survey by The Trevor Project, which conducts an annual poll on LGTBQ mental health, 45% of LGBTQ youth had seriously considered suicide in the previous year. That included more than half of transgender and nonbinary youth, and rates were higher for LGBTQ youth of color than for their White peers.

LGBTQ youth who faced anti-LGBTQ environments such as being discriminated against, experiencing violence or harassment, or being subjected to conversation therapy reported more than twice the rate of attempting suicide in the past year compared to those who did not have any of these anti-LGBTQ experiences.

“Although our data continue to show high rates of mental health and suicide risk among LGBTQ young people, it is crucial to note that these rates vary widely based on the way LGBTQ youth are treated,” said Myeshia Price, senior research scientist for The Trevor Project.

In fact, LGBTQ youth who found their school to be LGBTQ affirming reported lower rates of attempting suicide. And those who found their communities very unaccepting of their identities were more than twice as likely to attempt suicide than those who said their communities were very accepting.

Simply put, Price said, breaking down barriers to care and promoting acceptance helps to save LGBTQ lives.

LGBTQ students facing discrimination more likely to attempt suicide

% of students who said they attempted suicide by experience in their communities

Counselors skirt legal barriers

Despite this, the number of schools where LGBTQ students have access to care and other supports is diminishing as more states and districts pass anti-LGBTQ policies. Students describe wanting to feel welcomed and protected, yet they say adults in their schools fail to deter discrimination or to enforce protections.

“Many queer students I know are harassed daily but never get any assistance because they have no photo evidence,” Olivia said. “The school could more effectively deter discrimination if they emphasized that they harshly punish those who persecute queer students, but they keep the situations private for the sake of ‘confidentiality.'”

One school counselor even told how a newly elected local Wyoming school board removed “sexual orientation and gender identity” from the protected classes listed under the district’s bullying and harassment policy.

According to a report released by GLSEN in October, only a tenth of LGBTQ students surveyed said school staff intervened most of the time or always when overhearing homophobic remarks at school. Even fewer said school staff intervened most of the time or always when overhearing negative remarks about gender expression.

This is despite more than three-fourths of student respondents saying they had experienced verbal harassment based on their identity in the past year alone and almost a third saying they had been physically harassed, such as being pushed or shoved, in the previous year.

Mary, another LGBTQ student who is also part of GLSEN’s National Student Council and asked that her last name not be used due to her age, said she wished her school would more openly address harassment and discrimination. “There’s no shame of standing up for what’s right, so why are we hiding?”

For many school staff, it’s because anti-LGBTQ policies and fear of punishment have wedged them between a rock and a hard place.

A simple rainbow sticker, Olivia said, can help students feel at ease. But in places like Florida, even those were scraped off school walls and windows prior to the 2022-23 school year when the new law took effect.

In one New Orleans school, a school counselor had to replace a rainbow sticker, symbolic of a safe space, with a nondescript photo of a rainbow she bought online, said Haley Wikoff, assistant professor at Western Illinois University’s Department of Counselor Education.

“But it was her way of saying, ‘My students that need to see this will see it and know that I’m a supportive person,’” said Wikoff, who also sits on the ethics committee for the American School Counselor Association.

Multiple school counselors described having to find similar roundabout ways to make their LGBTQ students feel supported.

Elementary school students congregate at the table where Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the Parental Rights in Education, or the Don’t Say Gay bill, while supporters display “Protect Children” placards in Shady Hills, Florida, on Mar. 28, 2022.

Douglas R. Clifford/ZUMA Press/Newscom

In some places, stakes are higher than rainbows. Laws in places like New Hampshire and Florida require counselors or other school professionals to report students’ pronoun and name changes to their parents — essentially “outing” students’ identities before they are ready. Proposals elsewhere would require the same.

Even in places where such anti-LGBTQ laws are not in place, counselors are seeing what they describe as unusually high parental interest in LGBTQ-related matters.

In Iowa, a counselor said a school board meeting on transgender student policies triggered parents’ calls at Linn-Mar High School “to see their student records to find out if their student was identifying as a different gender at school.”

Sharing case notes, counselors say, is not only against standard practice, but can put student safety at risk.

However, school counselors working with students in public schools are not protected by strict confidentiality guidelines that may exist in clinical environments, said Amanda Fitzgerald, assistant deputy executive director for the American School Counselor Association.

“So, if notes are written down, it could tie the hands of school employees if anyone knows the notes exist,” Fitzgerald said, adding school counselor notes should be very vague and used primarily as memory joggers.

“In some cases, students have legitimate fear of neglect, abuse or abandonment when it comes to gender identity and sexual orientation, so it may be in the student’s best interest (in terms of safety) not to note these things in any kind of note system kept by a counselor as they may, at some point, be subject to a FERPA request,” Fitzgerald added.

According to The Trevor Project, only 37% of surveyed LGBTQ youth identified their home as a gender-affirming space. Likewise, fewer than 1 in 3 transgender and nonbinary youth said their home is gender-affirming.

A former counselor with over a decade of experience, who is now a counselor educator and spoke to K-12 Dive on the assurance of anonymity over fear of pushback from the community, suggested LGBTQ students in areas with anti-LGBTQ policies speak to counselors indirectly to preserve their confidentiality. Instead of saying they are seeking resources for themselves,they could say they are asking for a friend, for example.

“It’s incredibly important that we are upfront about the limits of confidentiality,” the former counselor said. “That can shut down a conversation with a student immediately, which I think is dangerous.”

According to The Trevor Project, while 82% of all LGBTQ youth reported wanting mental healthcare, more than half of those were not able to get it — an increase from past years.

The students who sought mental healthcare but couldn’t get it cited an array of obstacles. Among them: the fear of being outed.

People march during the Brooklyn Liberation’s Protect Trans Youth event in Brooklyn, NY, on June 13, 2021.

Michael M. Santiago via Getty Images

After Texas Gov. Abbott and state Attorney General Ken Paxton pushed to require licensed professionals to file child abuse reports against families of transgender students who are receiving gender affirming healthcare, that fear escalated.

Up until then, for Kimberly Shappley and her transgender daughter Kai, anti-transgender efforts had been an ebb and flow. But when Abbott’s order came out, Shappley described the situation as “a wreck.”

“It’s just been a lot of tears,” Kimberly said. “It’s been a lot of, ‘Do we have our documents in order? Do we have our plan in place? Is this the time we have to move?'”

Across the state, questions were raised about the role of educators and the impact on them, as well as about student well-being.

“Teachers, social workers, and other mandatory reporters were confused about whether they needed to report their students and clients” to Child Protective Services, alleged a lawsuit filed later by PFLAG, the first and largest organization for LGBTQ people and their allies. “Phone calls and messages to mental health and suicide crisis hotlines skyrocketed across the state, and incidents of bullying and harassment towards transgender students spiked in Texas schools,” the lawsuit said.

Despite the reported increase in bullying and harassment, the new order meant many students or families couldn’t turn to professionals for help.

“Trans youth may be hesitant to engage in these services if there is fear around their parents being reported for child abuse,” warned Sheila Desai, director of educational practice for the National Association of School Psychologists, at the time.

One student, identified in the lawsuit against Abbott as 16-year-old Antonio Voe, attempted suicide by ingesting a bottle of aspirin, according to court documents filed in the case. “Antonio said that the political environment, including Abbott’s Letter, and being misgendered at school, led him to take these actions.”

After his recovery at an outpatient psychiatric facility, Antonio and his family were investigated about child abuse. He later dropped out of in-person school. The lawsuit against Abbott’s child abuse policy is scheduled for a trial in 2023.

Another account included in the lawsuit was of a student pulled out of class and sent to an administrator’s office to be questioned by a Child Protective Services officer. Children also reportedly experienced anxiety, had a hard time sleeping, and performed worse in school, the lawsuit alleges.

Kai Shappley and her family moved out of Texas and into a safer state after Gov. Greg Abbott’s policy required licensed professionals, including teachers and nurses, to report parents of transgender children receiving gender-affirming healthcare as child abusers.

Them/YouTube

Counselors becoming ‘weaponized’ as more students need them

As anti-LGTBQ school policies and practices roll out, their link to poor student mental health and school performance is becoming clearer through surveys and anecdotal evidence.

An overwhelming majority of transgender and nonbinary youth said they have worried about transgender people being denied access to bathrooms and athletics due to state or local laws, according to The Trevor Project.

A separate survey conducted by GLSEN shows that students with more supportive staff at their school are almost half as likely to feel unsafe because of their sexual orientation, half as likely to miss school because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable, and felt greater belonging to their school community.

They also performed better academically and were more likely to plan on pursuing post-secondary education.

However, in 2021, the number of supportive school personnel reported by students was lower than in 2013 to 2019. Less than a quarter, or 23.7%, reported that their school administration was somewhat or very supportive.

On the flip side, students who experienced higher levels of victimization because of their identities were almost three times as likely to have missed school within a month’s time frame than those who experienced lower levels. They were also more likely to be disciplined.

Of the LGBTQ+ students who indicated that they were considering dropping out of school, half (51.5%), indicated that they were doing so because of a hostile school climate, including issues with harassment, unsupportive peers or educators, and gendered school policies or practices.

By the numbers

91%

Of transgender and nonbinary youth said they have worried about transgender people being denied access to bathrooms due to laws

83%

Of transgender and nonbinary youth said they have worried about transgender people being denied access to sports

52%

Of students cited hostile school climate, including harassment, unsupportive peers or educators, and gendered school policies or practices as reasons they are considering dropping out of school

24%

Of students reported their school administration was somewhat or very supportive of LGBTQ youth

Counselors and teachers describe trying their best to support their students — and yet feeling targeted by the community and lawmakers for doing so.

“Our profession has become weaponized,” said Jennifer Kirk, counselor and curriculum leader at Upper St. Clair High School in Pennsylvania. “There has been language and accusation that we as a profession are trying to indoctrinate students. And that is not something we’re doing.”

Kai and Kimberly, who spent years advocating for LGBTQ rights in Texas, have since sold many of their belongings and left the state with their remaining possessions packed in a car. They spent nights in hotel rooms and at roadside parks before temporarily settling in Connecticut, where Kimberly enrolled Kai and her brother in school.

She’s also created a GoFundMe to support her family’s move out of Texas after the governor’s child abuse policy went into effect — and into a state where her children feel safe.

“We’ve already had to move our family once because it was unsafe in the town that we came from,” Kimberly said in February. She’s even devised a plan to leave the country if the situation worsens.

Kimberly, in August, described feeling “like a frog in a pot of water” in the wake of Abbott’s policy who knew “the boiling point is soon and also that if I stayed there I may not recognize it until it was too late.”

“There are more political refugees like us,” she said, “Many more.”