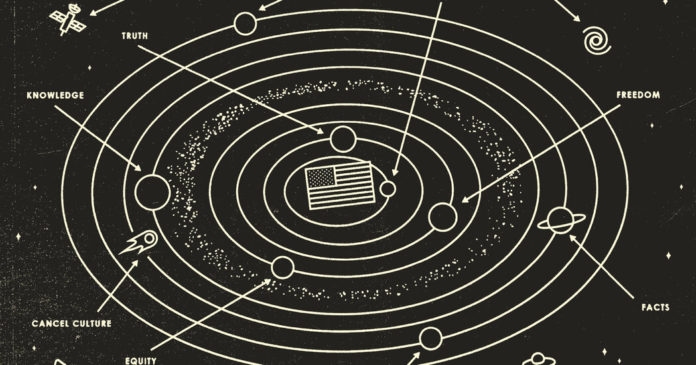

Just America “is concerned with language and identity more than material conditions.” This separates it from Marxism and also Martin Luther King Jr., whose demands for equal rights largely fell “within the framework of the Enlightenment.” According to Packer’s rendition of Just America’s ideology, on the other hand, “all disparities between groups result from systems of oppression and demand collective action for redress, often amounting to new forms of discrimination — in other words, equity. In practice, identity politics inverts the old hierarchy of power into a new one: bottom rail on top.”

Packer spells out the problems he sees with abandoning the Enlightenment framework. Fixating on language alienates sympathetic outsiders. It’s hard to build a coalition while constantly correcting how people talk. Symbolic fights distract elites while doing nothing to address economic hardship. Just America may also find itself out of touch with people it claims to represent. The activist push to defund the police in many cities, for example, “was stopped by local Black citizens, who wanted better, not less, policing.”

Packer is especially concerned about the academy and the media. Just America’s reigning focus on subjectivity and oppression of “the self and its pain — psychological trauma, harm from speech and texts,” he writes, has become “nearly ubiquitous in humanities and social science departments.” And some journalists are enforcing intellectual piety and purism, using “the power to shame, intimidate and ostracize, even turning it on their colleagues.”

As a journalist and a part-time lecturer at a university, I would have shrugged off these claims a few years ago. I still think a minority of academics and journalists are driving the shift Packer is talking about. But they have real influence. Which brings me to Jonathan Rauch.

Rauch’s subject, in “The Constitution of Knowledge,” is the building of human understanding. He takes us on a historical tour of how a range of thinkers (Socrates, Hobbes, Rousseau, Montaigne, Locke, Mill, Hume, Popper) sought truth, came to embrace uncertainty, learned to test hypotheses and created scientific communities. He is astute about the institutional support and gatekeeping that sustains “the reality-based community of science and journalism.” Social media platforms are bad at this because their profits are built on stoking users’ existing rage and spreading lies faster than truth. This is not a new critique, but it’s nice to see Rauch weave it into his larger project.

Online, Rauch argues (citing the political scientist David C. Barker), a “marketplace of realities” threatens to supplant a marketplace of ideas. He describes the danger the right poses, by trolling and spreading disinformation rather than seeking truth and checking facts.

But like Packer, Rauch reserves his most energetic criticism for the excesses of the left.

He blames it for cancel culture, defined as firing or ostracizing people for stray comments or social-media posts (some awful, some awkward, some expressing mainstream-until-yesterday views). He writes at helpful length about the difference between criticizing and canceling. “Criticism seeks to engage in conversations and identify error; canceling seeks to stigmatize conversations and punish the errant. Criticism cares whether statements are true; canceling cares about their social effects.”