In 2019, Columbus, Ohio, had seven reported cases of congenital syphilis, or cases in which a newborn child was infected during pregnancy. Two years later, that number rose to 20. And now?

“Year to date, we’ve already seen 28 cases,” said Dr. Mysheika Roberts, the city’s health commissioner. One of this year’s cases, she added, resulted in the death of a child.

Cases of congenital syphilis in the United States climbed by a whopping 184% between 2017 and 2021, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But that’s only one element of an explosive rise in sexually transmitted infections, known as STIs, which one expert in the field describes as an “out-of-control pandemic” that began in the 2010s and became super-charged during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Experts in public health say COVID-19 contributed to the rise in sexually transmitted infections by preventing people from getting routine health care, where STI screenings can occur. It also siphoned public health workers from STI work to focus on COVID-19.

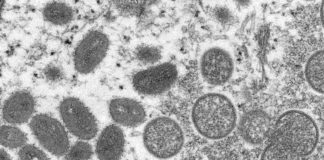

With COVID-19 still festering, a battered and underfunded public health workforce also is tasked with trying to turn the tide on the rising numbers of STI cases, now including monkeypox, which also is mostly spread during sexual contact.

“These are shocking numbers,” said David Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD (Sexually Transmitted Disease) Directors, who characterized the situation as “out-of-control.” (Harvey says, despite his organization’s name, it prefers the term STI as less stigmatizing.)

According to preliminary numbers from the CDC, the overall number of syphilis cases, which includes congenital syphilis and syphilis transmitted through sexual contact, rose nearly 70% between 2017 and 2021. It increased by nearly 28% in 2021 alone, the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, the rate of syphilis in the U.S. reached 51.5 cases per 100,000 people, the highest rate since 1990 and the greatest number of overall cases (171,074) since 1951.

The increase in congenital syphilis has been even steeper than for syphilis transmitted through sexual contact, 184.5% over five years and 24.1% between 2020 and 2021. In 2020, the last year for which the CDC has data, there were 149 stillbirths or infant deaths associated with congenital syphilis, more than triple the number from four years earlier.

“You can argue that every case is one that can be prevented,” Leandro Mena, director of the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, said in an interview with Stateline. They represent “a failure in our system,” he added. (Forty-two states and Washington, D.C., require at least one syphilis screening during pregnancy, although that occurs only if the patient is receiving prenatal care.)

Cases of chlamydia and gonorrhea also saw significant increases between 2020 and 2021, though not nearly as steep as those for syphilis. Like syphilis, the infection rates for chlamydia and gonorrhea have been rising for years, though the increases for chlamydia have been more uneven than the other two.

Overall, 2.5 million people in the United States were reported to have been infected with one of those three STIs in 2021. The CDC has not yet reported 2021 HIV numbers.

Not Enough Money

Mena said STI rates have been increasing for a decade, a trend he and many other experts attribute to a lack of sustained public health funding especially to combat STIs. Federal STI funding has been flat for nearly two decades. When adjusted for inflation, that amounts to a 40% funding reduction in that time, according to one study published in 2021 by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

This summer, Harvey’s organization asked the CDC for $344 million in additional funding to help bolster the capacity of state and local health departments to combat STIs with more hiring and staff training. It requested another $100 million to expand access to sexual health services in schools to curtail STIs, HIV and teen pregnancy.

Federal money often comes with restrictions, denying local public health agencies flexibility they say could make them more effective. For example, Columbus’ Roberts said the STI funding her city receives by way of the CDC restricts how much can be spent on screenings, even though screenings represent her agency’s biggest need.

“The limitations on the funding we get, on what we can and cannot use the funding for, is really a hardship,” she said.

Mena said the localities and states can have more flexibility in spending the federal STI money if they can justify it.

In passing last year’s American Rescue Plan Act, Congress approved $1 billion in public health spending over five years for confronting disease outbreaks. Some of that funding will be used in STI prevention and treatment.

“That doesn’t solve the problem, not even close,” said Rebekah Horowitz, senior program analyst for HIV, STI and viral hepatitis at the National Association of County and City Health Officials. “It’s a great investment in disease intervention, but we need services in STI clinics, provider education and outreach in communities.”

The funding shortfalls over the years resulted in the closure of many government-run STI clinics. That alone has helped propel the increase in STIs, advocates say. Research suggests that many patients prefer to go to such clinics for sexual health services, including for STI screenings and treatment. The most-cited reasons given were the availability of walk-in or same-day appointments and lower cost.

Fewer clinics, public health officials say, results in fewer STI screenings, less treatment and more transmission.

Other factors also have fueled the increase in STI rates. The CDC’s Mena cited the decreasing use of condoms by gay men and sexually active high school students. Long-term contraceptives have instead become an increasingly popular form of birth control for heterosexual high school couples, while gay men are less likely to use condoms because there are now highly effective anti-viral drugs for HIV.

Harvey, of the STD directors coalition, also pointed to the fall-off since the 1990s in STI education directed at young people and medical providers. In both cases, he said, the decline has resulted in less screening and therefore less detection.

He also said the epidemic of opioid and methamphetamine use in the past two decades has helped propel the rise of STIs. Research has demonstrated links between drug use and STIs.

“Meth and opioid are at the intersection between substance abuse and sexually risky behavior,” Harvey said.

Reductions Unlikely Soon

All of that was going on when COVID-19 hit in 2020 — but the COVID-19 pandemic made the situation worse.

Access to health care was sharply curtailed, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, which translated to even fewer STI screenings and less treatment, officials say. In Columbus, Roberts said, her STI outreach staff didn’t provide services at community events because those events were canceled.

Public health officials also suspect that for many people, COVID-19 revved up sexual activity at a time when other recreation was foreclosed.

“One of the things you might do other than going to bars is have sex,” Horowitz said.

COVID-19 also forced many public health workers who had been focused on STI surveillance and testing to shift their focus to COVID-19.

“People in STD prevention were detailed to address COVID and now monkeypox and, in some places, polio, so that has reduced staffing and disease prevention capacity for STDs,” said Kate Heyer, senior director for infectious diseases at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “And that is a workforce that was strained to begin with.”

It’s a familiar pattern that didn’t start with COVID-19. Short on funding, public health agencies often shift resources to meet the crisis of the moment.

“We’ve had Zika, Ebola, COVID and now monkeypox. All those things rely on the same skill sets in local health department as STIs,” Horowitz said. “We don’t have new folks coming into public health who can do STI and all the other emerging infectious diseases as well.”

As COVID-19 ebbs, Horowitz expects the steep increases in syphilis rates to slow down. But decline? Not without more resources, she said.

“I’m hopeful we will not see increases like we have been seeing, but I’m not anticipating we will see reductions,” she said. “Not in the short term.”