There was a rhythm to life on The Land, a sweet cadence in the place up Sherwood Road, just outside Willits in unincorporated Mendocino County.

The days began at first light — a meal, perhaps, followed by the gathering of firewood. Early on, in the ’70s, days were spent building: constructing homes from scraps, developing a spring for running water, planting a garden and building a fence to keep the deer out. At dusk, before the only light around came from flashlights, ingredients were gathered and a fire started. There was singing, too, and lots of laughter on this Northern California land, claimed and staked for women.

“Heaven” is how one woman described it.

As the years passed, the community grew and then shrank until Sally Miller Gearhart was the only one left, the lone holdout living on The Land year-round. Gearhart was a woman of many accomplishments. She wrote some of the first speculative lesbian fiction. She helped establish one of the nation’s first women’s studies programs at San Francisco State University. And she stood alongside Harvey Milk as he fought to defeat the anti-gay Briggs Initiative in 1978.

Sun shines through the thicket a few hundred feet above Sally Gearhart’s home on “Sunspot,” the adjacent property owned by Susan Leo outside of Willits (Mendocino County).

Alexandra Hootnick / Special to The Chronicle

But the country setting had always called to Gearthart, so this was the place where Deborah Craig, a documentary filmmaker, found her in 2014. Now, with many of Gearhart’s achievements lost in the haze of history, Craig is working toward completion of a film to introduce Gearhart to a new generation.

“When I first met Sally, I was like, ‘What went wrong?’ She’s here, she’s alone, she’s in the woods. This is a sad story. It’s not going to end well,” Craig says. “And we spent months and months, if not years, trying to figure out what happened.”

When Deborah met Sally

Craig never sought out Gearhart, not specifically. As so often happens, one thing led to another.

Her name came up in the course of a different project, about lesbians and aging, that Craig was working on while pursuing a master’s degree in public health.

“I was just told, ‘Oh, I know a woman you might want to interview — she still lives on a women’s land community in the woods in Northern California, and she’s in her 80s and she still cuts her own firewood with a chainsaw.’”

That visual was everything.

“I wanted a picture of that,” Craig says. “I wanted videotape of that.”

Now Playing:

She got that tape and more, when she met Gearhart at her home, tucked away in the hills outside Willits. Craig got her, late into her 80s, dressed in all denim, save for a white T-shirt and white Nike tennis shoes, driving around in a beat-up Jeep, seats all foam and springs, careening up and down dirt paths, shouting at the camera: “You OK back there?”

She got Gearhart blowing smoke rings. She got Gearhart rolling under a barbed-wire fence, dusting off her hands on her pants and turning to the camera as she pulled down the metal braids for Craig, like an invitation to follow. “Would you like for me to hold the camera for you?”

And she put all this in the early drafts of her short film, along with moments from the lives of other women, making their own ways into advanced age.

“Everybody who saw the footage was like ‘Who is this? She’s so amazing. You’ve got to make a film about her. … You shouldn’t do a film about aging, you should just do a film about Sally.”

By the time Craig had finished her short, she’d grown to agree.

The making of an activist

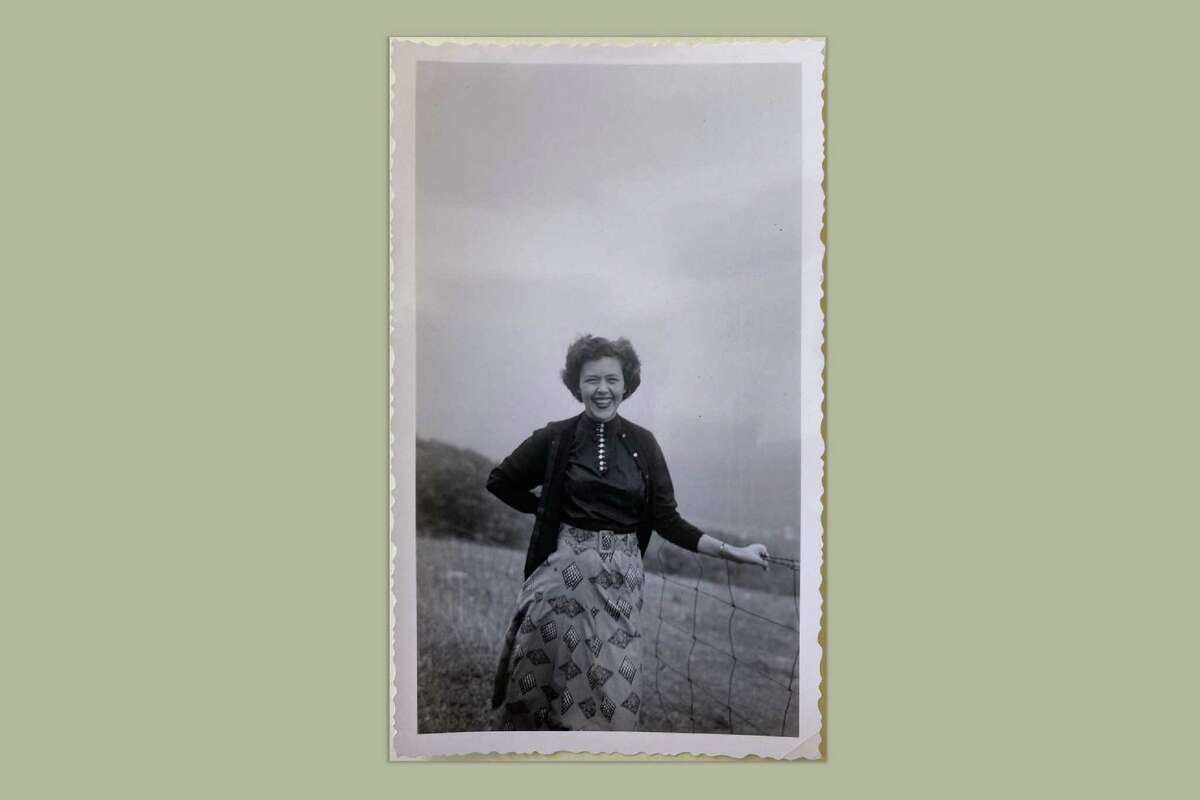

Sally Gearhart in high school. She was raised in Virginia, near the Appalachian Trail.

University of Oregon Libraries

Almost everybody starts by describing Gearhart’s voice, though the descriptions often seem to contradict one another. “Deep.” “Beautiful.” “Booming.”

“I loved listening to her talk,” says Cleve Jones, a longtime gay rights activist, and a contemporary of both Gearhart and Milk. “And sometimes I thought what she was saying was just crazy. But I never got tired of listening to that voice.”

Gearhart was tall — 5 feet 9 — with big hair and a broad (and warm) smile. She didn’t shave her armpits, but she almost always wore lipstick. One friend (and Land partner), Bonnie Gordon, described her as having a butch exterior and femme interior.

She was a lesbian separatist who spent a lot of time with men. A conservationist who said prayers for fallen trees and, later in life, sought commonality with the same loggers she’d once flipped off as they drove trucks through Willits. She fought conservatives’ attempts to ban queer people from public life by matching them, verse for verse, with her knowledge of the Bible.

The night that Milk died, she set police cars on fires in protest — or she spoke to the crowd telling everybody to remain calm. It depends on who you ask.

All these contradictions make her an interesting topic for a documentary. They also make her a difficult one. History gets clarified in the retelling, and Craig has chosen to make a first draft, to gather all the disparate threads and weave them together.

Craig and her crew have interviewed more than four dozen people, logging hundreds of hours of footage. Talk to that many people and a person, a narrative, becomes complicated, almost unruly. “The whole thing about Sally is the more we found out about her, the more interesting and complicated we found out she was.”

Sally and her many lives

A studio portrait of Sally Gearhart from the 1940s and at the time of graduation from the University of Illinois in 1956.

University of Oregon Libraries

The trouble with making a documentary about Gearhart is there wasn’t just one of her; she was the sort of person who packs multiple lives into a single lifetime.

She was born 1931 in Pearisburg, Va., a small town on the Appalachian Trail, and raised by her grandmother, following her parent’s divorce.

Later, at Sweet Briar College, a nearby private women’s institution, she charmed her classmates with that voice — by singing and acting, being big and taking up space, according to Pat Winks, a friend who lived down the hallway at the time.

“Sally drew herself to people. She was someone who wanted to know you, wanted to know what you were like,” Winks told Craig during a day of filming in her San Francisco home. “You like somebody who wants to know you. That was Sally.”

Winks knew Gearhart was a lesbian in college, most everybody did, but, she says, “we didn’t talk about it, really.” That might have been the way Gearhart kept living, quietly and in the closet — and for many years she did as she pursued a master’s, then her doctorate, and settled down for a life in academia, teaching speech and theater in Texas in the ’60s. “For ten years, she taught passionately, judged beauty contests, and publicly denied the reality of her personal life and convictions,” writes Christine Cole in a short biography on Gearhart’s personal website.

By 1970, though, Gearhart had made up her mind to move to San Francisco, intent on becoming a different, open version of herself, no matter the costs.

This is when the Gearthart that most people know was born. “I heard from one of her close friends fairly early on, Sally would not have become Sally if she didn’t come to San Francisco,” Craig says. “She could have stayed in the South. She had a tenure track job. She could have stayed in the closet.”

Filmmaker Deborah Craig attended the memorial for Sally Gearhart at Recreation Grove in Willits in 2021.

Alexandra Hootnick / Special to The Chronicle

From 1973 to 1992, Gearhart taught at San Francisco State University, earning tenure as an out lesbian, a considerable feat given the politics of the time. This is where she met Jane Gurko, too, her life partner and devoted friend — even after their romantic relationship ended. Together, they helped “initiate a ground-breaking curriculum experiment” that would become one of the first women’s studies programs in the nation.

“She was a wonderful teacher and just so engaging and so welcoming and so affirming of everyone,” says Bonnie Gordon, a student of Gearhart’s and later a resident on The Land. “I told (a) friend who had taken a class with her … ‘You know, I really have a crush on Sally.’ And she said ‘You and every other woman in San Francisco.’”

During this time, Gearhart became a fixture of lesbian activist spaces. She spoke out against discriminatory politicians. In 1977, she was among the 26 gay men and women featured in the seminal documentary “Word Is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives.” This is how many people, including historian Estelle Freedman, first encountered Gearhart.

“She was stunning, such a powerful, charismatic speaker, and so thoughtful,” Freedman says. “By claiming her lesbianism — this was not something visible in film, television, literature in classrooms, you simply didn’t see it.”

It was during this time that Gearhart began to write, too — essays and books about women’s rights and lesbian activism, asserting, in one piece’s title, that “The Future — If There Is One — is Female.” In her political writing, she sometimes put forth explosive proposals — reducing the percentage of men (over time) to just 10% of the population, for example.

Susan Leo, a friend who bought the property adjacent to Sally Gearhart’s stands next to Jean Crosby, one of Gearhart’s original land partners outside of Willits in Mendocino County on Sept. 19, 2021.

Alexandra Hootnick / Special to The Chronicle

“It was evocative hyperbole,” says Susan Leo, one of the women called to The Land. “Sally wanted people to think seriously about the violence and the culture of violence perpetuated by the patriarchy.”

In her science fiction, Gearhart used words to carve speculative futures where these ideals were allowed to live. She created worlds where, as author Jewelle Gomez put, “women were not victimized.” Gearhart was not the first to do this, she wrote alongside other, better known authors, most notably Octavia Butler. But Gomez remembers the impact of Gearhart’s serialized stories about “The Wanderground,” a land where women, psychically connected, formed a utopian existence, away and free from men. The stories were collected and released under that same name in 1979; it remained in print for more than 20 years.

“It really did create a stir because it was just one of the first books, I would say, that imagined a world in which a community of women was self-sufficient, protected itself,” Gomez says. “She set the pace for a lot of other writers who came after her with just that one book.”

Around the same time as she wrote about these “hill women,” Gearhart, her partner and two close friends began to cultivate a community in the hills of Mendocino County. “Feminist utopian ideals. Freedom. Land ownership. Country life.” All of that drew Gearhart away from big city life, which she “always felt to be a necessity not a preference,” Leo says. “After a long search, she found Willits and it felt like home.”

‘A guiding light’

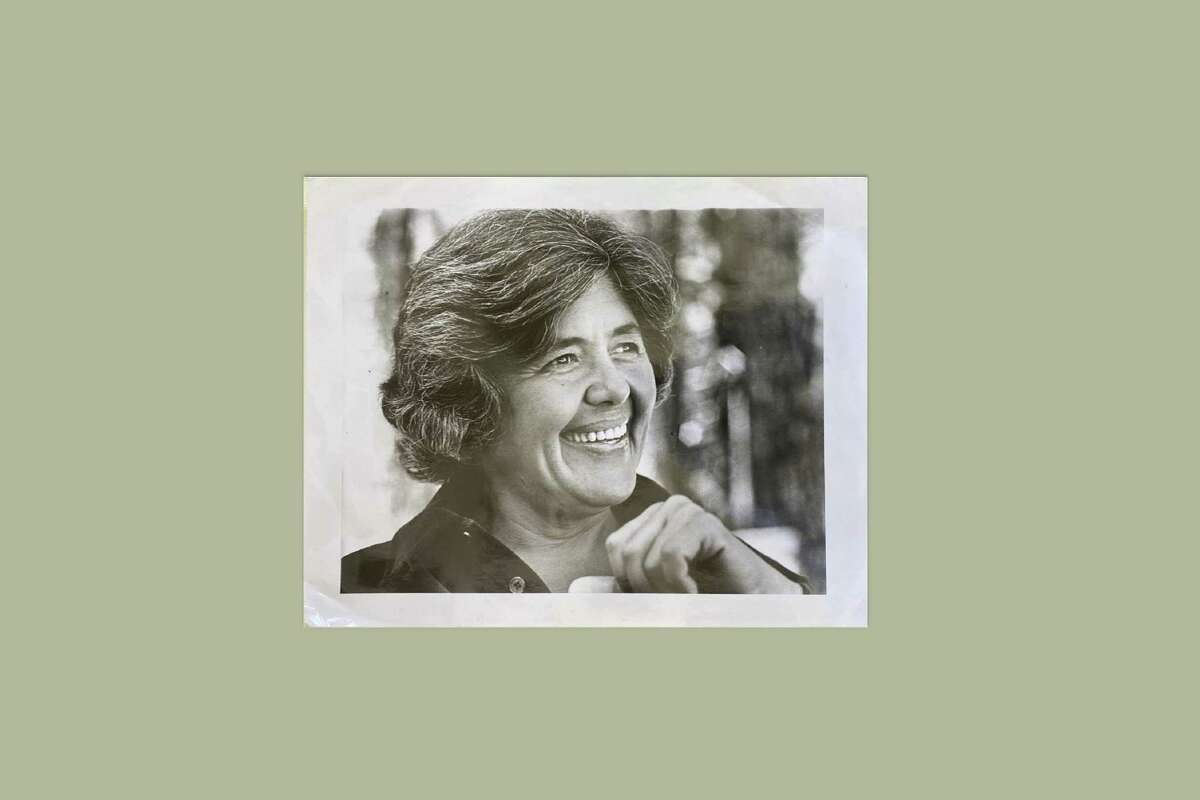

Sally Gearhart in 1979, after she had moved to San Francisco.

Deborah Snow/University of Oregon Libraries

The morning interviews stretched into the early evening as Bonnie Gordon and Penny Sablove shared stories about Gearhart, one of their closest friends. They were among the many land partners who made a home (theirs was called Corazón) outside Willits, so they knew her with a keen sort of intimacy.

Gordon spoke about how Gearhart collected “people on the fringe.” This was a woman, Gordon said, who fed raccoons and held a deer as it died.

Sablove called Gearhart “a guiding light.” People got it wrong when they called her a “separatist.” It wasn’t that she disliked men. “She just wondered what would women, would girls, be like without all the crap they must deal with.”

Craig nodded along as they spoke. She never rushed to fill pauses; she let Gordon and Sablove do that instead.

Through her questions, Craig tried to pull the details of people’s Sallys from decades in the past.

When the day was nearly up, Craig had “one last question” for Penny — the same question she always liked to end on.

“Is there anything you’d like to thank Sally for?”

Penny thought for a moment.

“I want to thank Sally for her generosity.”

Cut from history

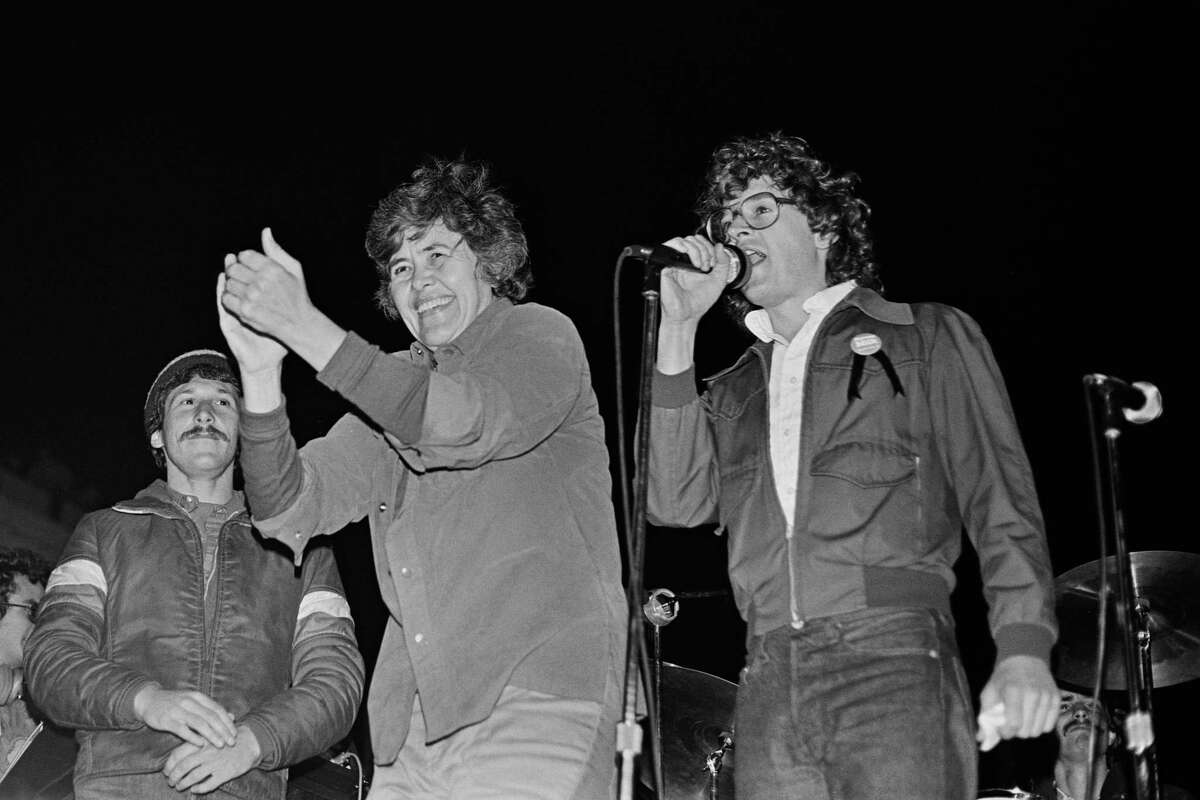

Sally Gearhart and Harvey Milk at a rally at Everett Middle School on Church Street in support of No on 6, in 1978.

Steve Savage / Steve Savage

There’s a scene in “Milk,” the 2008 Academy Award-winning biopic about the life of San Francisco activist and politician Harvey Milk, where Milk faces off against John Briggs, a California state senator, who, in the late ’70s, had proposed banning gay people from teaching in public schools.

The two men meet in an Orange County school gymnasium, a moderator between them. The crowd is hostile, but Harvey delivers a zinger: “You, yourself, have said there’s more molestation in the heterosexual group, so why not get rid of the heterosexual teacher?”

Only something is missing from the scene: Gearhart. In truth, she and Harvey sat side by side during multiple debates against Briggs.

The activist Jones says he’d introduced the two for exactly this reason — together, he figured, they’d soften and complement one another. “She and Harvey were just this great team because Harvey was sort of New York, Jewish …. There’s a bit of edge to him, you know, a little bit sarcastic,” Jones says. “And she had this southern inflection and this background in theology.”

By some accounts, it was Gearhart who was the standout against Briggs, though most of the film from those debates has been lost, at least for now. Jenni Olson, the archival researcher for the documentary about Gearhart, calls it “the holy grail.” But one can get a small taste, from a brief clip Craig uses in the trailer for her film.

“Overwhelmingly, I might add, it’s the heterosexual man who are the child molesters,” Gearhart says in the clip.

“I believe that’s a myth,” Briggs responds.

“Oh, senator, the FBI, the National Council on Family Relations, the Santa Clara County Childhood Sexual Abuse Treatment Center and on and on and on,” Gearhart said, citing a list of studies about the topic.

Her absence in “Milk” was a harsh indictment, for those who loved and knew her, of how Gearhart’s contributions to the movement — and the contributions of so many women — could be so easily ignored.

Sally Gerhart and Cleve Jones at Harvey Milk’s birthday street party just one night after the White Night Riots on May 22,1979.

Daniel Nicoletta

Leo remembers watching “Milk” with Gearhart. “She just rolled her eyes and was like ‘Well, that’s typical.’”

There is a version of “Milk” that included Gearhart and her deep and honeyed voice. Dustin Lance Black’s earliest versions of the screenplay included her, right alongside Harvey, true to the mom-and-pop front they presented on stage those decades ago.

But a biopic is not a documentary, and Black faced pressure to trim the script. Big characters who show up late in the third act, like Gearhart, he said during a phone call from London, “are often the ones who never make it to screen.”

He made a point, some years later, to write her into a mini series about the movement he wrote for ABC, but the point, really, is this: “Sally is deserving of a film of her own.”

“Film has the power to help people see,” say Olson, the archivist, “to help people latch on” to history.

“Our history, queer history, has been buried. And it’s been buried because until very recently — and hopefully never again — our lives have been illegal,” Black says. “There is a vast mosaic … of queer foremothers and forefathers. And these stories must be told. But first they have to be excavated.”

‘She loved everybody’

Sally Gearhart called her house outside of Willits (Mendocino County) “Warmer Climes.”

Alexandra Hootnick / Special to The Chronicle

There are no signs to help direct a person to the place up Sherwood Road. A hand-drawn map on pink paper is about as good as it gets.

On The Land, the leaves falling from the Black Oak trees sound like rain when they hit a roof — and like snow when they meet the bottom of a boot. Dirt paths cut through tall, and tick-filled, grass, connecting one home to another, most with their own names — Bay Tree, Corazón (“heart” in Spanish), Terpsichore (the Greek muse of poetry and dance) and Sunspot.

Near Gearhart’s old home, there’s a tall madrone with knots in its smooth bark that look a lot like a woman’s breasts. Whether she ever noticed, we might never know. But Vivian Power, a friend of Gearhart’s, laughed as she pointed them out — the knots; the breasts — on a cool morning last winter just before she poured some of Gearhart’s ashes into a gnarled nook at the base of the very same tree. “I really have a feeling she built … here because of its size.”

Power met Gearhart when she showed up to a Spanish class that Power was teaching. Gearhart wore high heels, unusual for Willits. “This giant figure,” Power says. She had to force herself to look away, to make eye contact with the other students. They became close friends, and Power was with Gearhart in the days leading up to her passing.

After Power had emptied the small jar of Gearhart’s ashes, she paused, taking in the moment.

“She loved me. I mean, she really did,” Power said. “She loved everybody. This came up at her memorial how everybody that got there just thought, ‘Oh, I am her best friend.’

“She made everybody feel that way.”

Sally in her own words

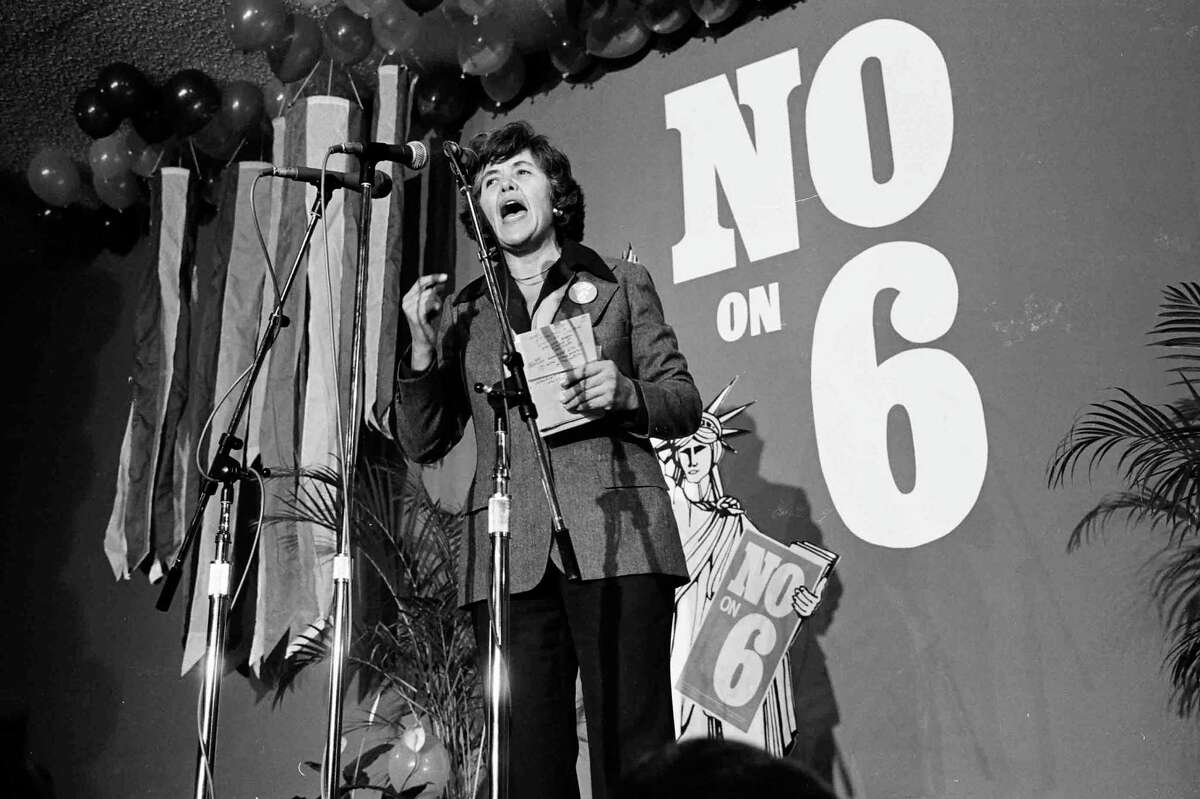

Sally Gearhart takes the microphone during a No on 6 victory party at the Shed, a nightclub on San Francisco’s Market Street, in 1978.

Steve Savage / Steve Savage

In the first half of 1995 — two decades into living on The Land, on and off — Gearhart wrote and revised an essay titled “Notes From a Recovering Activist.” She wrote about her past and her time taking to the streets.

“I marched and rallied and picketed, raged and wept and threatened, crusaded and persuaded and brigaded,” she wrote. “But I’m giving it up.”

Don’t mistake her, she writes, “I feel more passionately than ever about issues of justice and peace and environmental health. But I’m going about my life in a different way, a way in fact that I’ve scorned for twenty-five years.”

She’d stopped trying to change people, she writes. “I’m assuming that cleaning up my own act is the best contribution I can make to any cause.”

She imagined the reader rolling her eyes. But, while she might have, five years earlier, cursed at a logger carrying dead trees down a highway; or, two years prior, prayed he might see the error of his way; now she was making no effort to judge or to change him, but simply trusting that the “acknowledgment of our kinship can make a positive difference in the texture of all of our lives.”

She understood the holes in this line of thinking, but after all her years and all of her lives, it’s where she wound up.

Maybe living on The Land, in a small world of her creation, taught her something about the wider world. Lauretta Molitor, who is running sound for the documentary, has given this some thought.

“None of us are static and set in stone,” she said some months ago during an interview. “As strongly as she might have held certain views … we all evolve.”

A funeral, and dancing

A framed photograph of Sally Gearhart was placed on the stage where a memorial was held for her on Sept. 19, 2021.

Alexandra Hootnick / Special to The Chronicle

Ideally — “in the best of circumstances” — Gearhart would have dropped dead on a dance floor and all the witnesses would “rejoice with me.” At least that’s how she imagined her death in a rather detailed document dated 2001.

Her end, though, wasn’t quite as she imagined.

On April 15, 2021, Gearhart’s friends gathered on the land for her 90th birthday. That was a Thursday. Three days later, she moved to an assisted living home nearby, where she spent the last of her days.

Gearhart had strict instructions for what to do in the event of her death. She was fine, even glad, to give her “body parts” to save the lives of baboons or other “nonhuman primates,” but she’d permit a donation to another human only on the condition that using animal body parts in humans was, by the time of her death, unlawful.

“Otherwise, keep all my parts and products with the body they know and love, letting them all share a common demise,” she wrote in the same document in which she had detailed her death on a dance floor.

Her body, she suggested, could possibly be mulched and made into dog food or dropped on the Alaskan tundra as a meal for the polar bears.

If none of that was possible, cremation would suffice. As for the funeral: “If there’s a need for some sort of ‘closure occasion,’ please just be sure it’s a celebration and that there’s lots of dancing and singing.”

People dance at Sally Gearhart’s memorial in Willits (Mendocino County) in September 2021.

Alexandra Hootnick / Special to The Chronicle

So that’s how it went on the day of Gearhart’s “celebration of life,” nearly one year ago, in a park in downtown Willits.

There were speeches and songs and poetry, all dedicated to Gearhart, a woman who helped shape more than one movement and usually ate standing up — handfuls of Goldfish or Ritz Crackers, washed down with Pepsi, followed by canned frosting for dessert.

Craig spoke, too. The truth is, over the course of making the documentary, Craig became a part of Gearhart’s life and Gearhart became a part of hers.

“I don’t think it’s possible to step all the way back ever,” Craig says. “I mean, you couldn’t know Sally or even make a good film about her without getting some kind of emotional attachment — a connection not just to her, but to the people surrounding her.”

As it stands now, Craig hopes to hit a late 2023 film festival run. She just won a $25,000 grant from the Berkeley Film Foundation to help with the completion of the project.

Not even Craig knows what that film will look like by then.

The challenge before her, now, is to resurrect this woman for a wider audience, and to reconcile all her many lives: Sally, the student; Sally, the professor; Sally, the author; Sally, the activist; Sally, the lesbian separatist; Sally, the woman living on The Land until the end.

Ryan Kost is a former San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: metro@sfchronicle.com