I had seen this woman before. Many times now. I was certain of it.

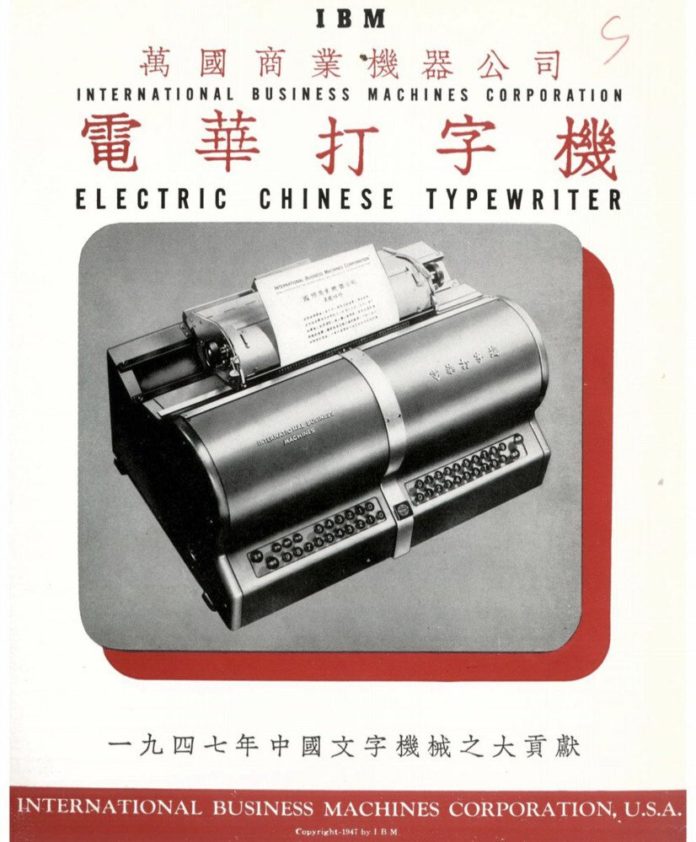

But who was she? In a film from 1947, she is operating an electric Chinese typewriter, the first of its kind, manufactured by IBM. Semi-circled by journalists, and a nervous-looking middle-aged Chinese man – Kao Chung-chin, the engineer who invented the machine – she radiates a smile as she pulls a sheet of paper from the device. Kao is biting his lip, his eyes darting between the crowd and the typist.

As soon as I saw that film, I began to riffle through my files. I am a professor of Chinese history at Stanford University, in the United States, and I was years into a book project on the history of modern Chinese information technology, and the Chinese typewriter specifically.

By that point, I had amassed a large and still-growing body of source materials, including archival documents, photographs, and even antique machines. My office was becoming something of a private museum.

As I thought, I had indeed encountered the typist in my research, in glossy IBM brochures and on the cover of Chinese magazines. Who was she? Why did she appear so frequently, so prominently, in the history of IBM’s effort to electrify the Chinese language?