Five neighboring brick buildings on the 700 block of Montgomery Street have maybe seen more history than any other street in San Francisco.

One was constructed on the hull of an abandoned ship; another saw the first meeting of a secret fraternity. The most infamous lawyer in the city worked in one; Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera once painted masterpieces next door.

The historic row’s five facades, still standing strong in the shadow of the Transamerica Pyramid today, look almost identical to when the city was built in the gold-fevered 1850s, when the buildings backed onto the shoreline of what was then Yerba Buena cove. Even the great earthquake and fire of 1906 couldn’t topple them.

The 700 block of Montgomery Street, San Francisco, 1934.

Archival

Montgomery Street, San Francisco, Dec. 2022.

Charles Russo / SFGATE

Here’s a walk through the history of one of the oldest blocks in San Francisco: five buildings the national register of historic places calls “the only physical reminders of the city’s beginnings.”

722 Montgomery Street

The two-story black and brick building at 722 Montgomery – currently the home of a high-end outdoor clothing shop – was built into the mud of the old bay shoreline around 1851. The New Orleans-style structure started out as a cigar warehouse but soon became the Melodeon Theater, a short-lived concert hall. According to a 1960s city planning document, when 722 Montgomery was a theater, tunnels connected the hall to others across the alley. The Melodeon is most known for providing a stage to Lotta Crabtree, one of the most famous, and wealthiest, entertainers in 19th century America.

Born in New York City, Crabtree moved to California after word of gold spread east in 1851. After some years touring mining camps in the Sierra foothills to entertain miners with her banjo, Crabtree settled in San Francisco in 1856, where she entertained the men of the Barbary Coast to huge fanfare on Montgomery Street. In 1864 she moved back to the East Coast to continue her career, which eventually made her the highest-paid actress in America. Crabtree’s scampish performances, including stuffing coins in her stockings and twisting her fingers in her dimples, left such a mark on San Francisco that the city honored her with a fountain on the corner of Market and Kearny.

Montgomery Street, San Francisco, Dec. 2022.

Charles Russo / SFGATE

That landmark is maybe most famous for providing a emergency meeting point for residents during the 1906 earthquake and fire. For over a century, at 5.12 a.m. on April 18, survivors of the quake would gather at the fountain to mark the anniversary. (The last survivor of the earthquake, William Del Monte, a three-month-old baby during the quake, died in 2016.)

Beyond housing the theater where Crabtree wowed the young men of the young city, 722 Montgomery Street was also home to the lavish offices of Melvin Belli, one of the most famous lawyers in America.

If San Francisco made the national evening news for any reason in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Belli was likely somewhere in the shot. The larger-than-life character represented everyone from Chuck Berry to Muhammad Ali out of his Montgomery Street office that was decorated like a “high end Victorian bordello,” according to one report.

A view of 77 Montgomery Street, on Dec. 9, 2022.

Charles Russo

The Belli Building at 722 Montgomery Street, Aug. 16, 1964.

Image via San Francisco Public LibraryA recent view of 722 Montgomery St., left, alongside a photo of it from August of 1964 when it was the Belli Building. (Images by Charles Russo & via SFPL)

Belli helped the Rolling Stones stage one of the must disastrous rock concerts of all time there, and defended Jack Ruby, the man who shot the man who shot JFK. While not in court or on the television, he spent his days in the offices of this storied Montgomery block, where he was once delivered a personal letter from the Zodiac Killer.

712-14 Montgomery Street

Currently home to a swanky cocktail bar and art gallery, in the 1850s and ‘60s, 712 Montgomery was a busy immigration station handling the influx of tens of thousands of men to the new city. In later years it housed a liquor store, a dry goods store and wine merchants. While the building’s history lacks the famous residents of some of its neighbors, it did make the front pages in 1909 for a bloody, and deadly, street battle.

The feud started on when two Sicilian brothers, Luigi and Antonio Ballangiero, found their cousin and “mortal enemy,” Vincenzio Ballangiero, on Montgomery Street. The Italian plasterers alleged that Vincenzio had stolen their tools some days earlier.

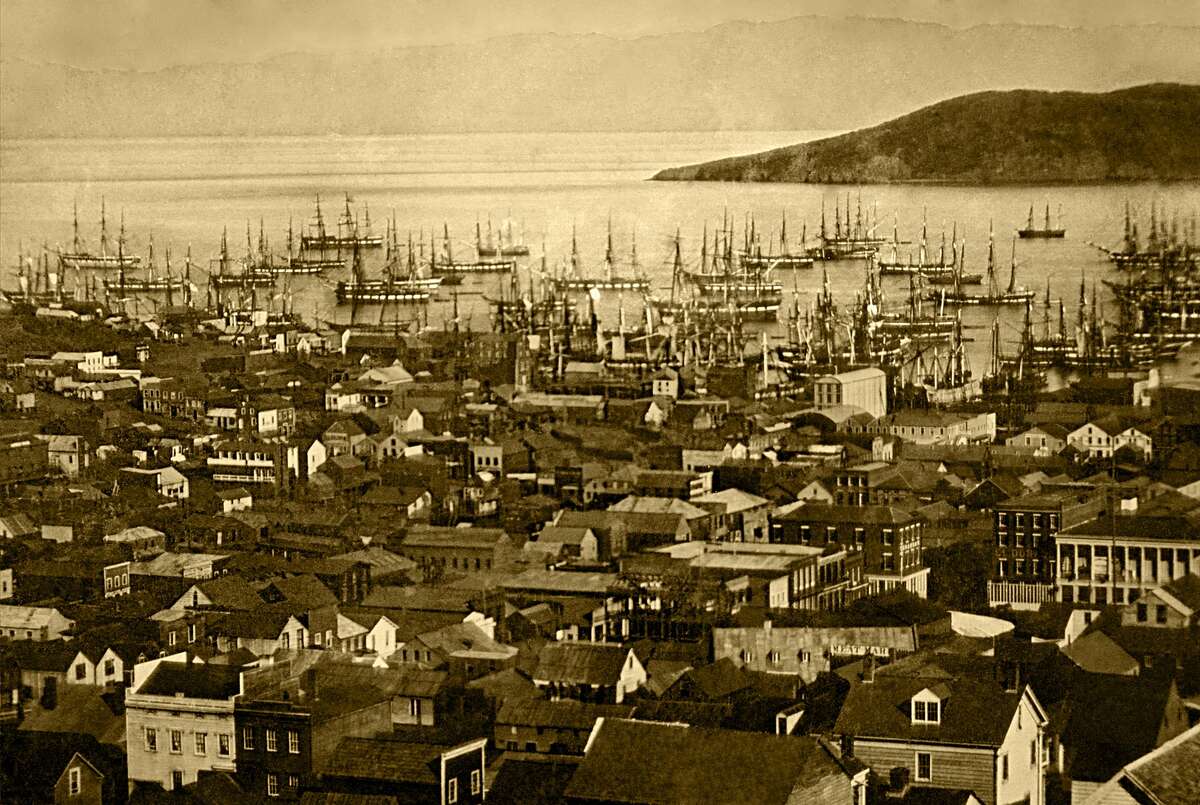

This photo of the port of San Francisco in 1851 shows the old shoreline of Yerba Buena cove, which ran behind Montgomery Street. By 1870 the cove was filled in, giving the city its new, current waterline on the bay.

Wikimedia Commons

“Luigi and Vincenzio flew at each other’s throats and reeled about the sidewalk, locked in a close embrace,” The Call reported. “They fell against the window of a dry goods store at 714 Montgomery, crashing through it, and then fought down to a position in front of C. Cavllo’s grocery.”

Vincenzio Ballangiero then drew his revolver and shot his cousin Luigi dead in front of Luigi’s brother, Antonio. In attempting to avenge his brother’s death, Antonio fired a shot at Vincenzio, missed his target and hit an very unlucky Italian grandma, Rosa Baglietto, who was walking her five grandchildren a block and a half away. Papers say the bullet “sped 400 feet” before hitting her in the neck.

Antonio was then “captured by a crowd,” as Vincenzio made his escape on foot down Taylor Street, a block west.

BEST OF SFGATE

Vengeance stayed in the air on Montgomery Street after residents learned that the loved grandmother had been shot and was fighting for her life, and that one of the shooters was on the lam. “If the police do not punish Ballangiero, I will,” the grandma’s son told the San Francisco Call.

The following day, San Francisco police notified authorities in New York City to be on the lookout for Vincenzio, speculating he may return there to travel back to Sicily and evade capture. Records show the grandmother of five survived the gunshot wound to the neck, but died three years later in San Francisco. There is no evidence that Vincenzio was ever seen again after making his escape down Taylor Street.

708-710 Montgomery Street

Now a fancy French eatery and an art gallery, the building at 708 – 710 is notable for its facade’s circular windows and giant gold and green “Canessa Printing Co.” lettering.

Montgomery Street, San Francisco, Dec, 2022.

Charles Russo / SFGATE

A view of the Canessa Printing Co. lettering on 708 Montgomery.

Charles Russo/SFGATE

Montgomery Street, San Francisco, Dec, 2022.

Charles Russo / SFGATEViews of 708 Montgomery. (Charles Russo/SFGATE)

The building is the only of the row of five that suffered significant damage during the earthquake and fire of 1906. This photo shows its upper story collapsed days after the big shake. The Canessa lettering was built a few years later, according to a sketch of the new facade in a 1913 edition of Italian language newspaper, L’Italia.

The building is most notable for being the site of the Black Cat Cafe between 1933 and 1964.

In the ’40s and ’50s under the stewardship of owner Sol Stoumen, the bar became the epicenter of the San Francisco beat scene and a gathering place for the city’s gay community. Allen Ginsberg once described the Black Cat as “the best gay bar in America. It was totally open, bohemian, San Francisco.”

Famed drag queen Jose Sarria, who later became the first openly gay candidate for public office in America, got his start singing opera librettos on the tabletops of the Black Cat.

After a campaign of harassment from the San Francisco Police Department, in 1949, authorities took Stoumen’s liquor license away. Stoumen, a heterosexual Holocaust survivor, protested the decision in court, which culminated in the 1951 landmark California Supreme Court case Stoumen v. Reilly, in which the Black Cat won. The case is considered the first in the country to state that police cannot interfere on public gatherings based on sexual orientation/identity.

The win, however, was short lived. After further raids and targeting from the SFPD and the city’s Alcoholic Beverage Control agency, the bar lost its liquor license on Halloween night, 1963.

726-728 Montgomery Street

726-728 Montgomery – also know as the Genella Building, after a china and glassware shop set up there by a man named Joseph Genella in the early 1850s – was also once the site of gold bullion dealers and a Spanish newspaper, according to San Francisco archivists, Noe Hill.

Curiously, a rusted plaque that has since been removed from the Genella Building’s red brick front described why the structure may be more consequential in the city’s history. The marker, as seen in a 2004 photograph here, claimed the site to be the “Birthplace of Freemasonry in California.” A look at Google Street View’s historical function shows the building was shrouded in a net and scaffolding for years starting in 2008 – it’s likely the plaque was removed around then.

A view of the brick facade at 726-728 Montgomery – also know as the Genella Building.

Charles Russo/SFGATE

An 1887 San Francisco Examiner column titled “Fraternal World” may shed some light on the building’s provenance as the first Masonic lodge in the state. It reported that a Freemason named Brother Levi Stowell was sent to California in 1848 to “open and hold a lodge in San Francisco, and that lodge was opened at that place in October 1849.” The California Historical Landmarks website currently lists the plaque as “missing.”

Like the other four buildings on that row, the Genella Building somehow survived the fires of the 1850s and the earthquake and fire of 1906. The relatively smaller 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, however, did significant damage to The Genella Building and the adjacent Belli Building, leaving them vacant for 25 years.

716-720 Montgomery Street

According to a notice affixed in its doorway today, the structure at 716 Montgomery – aka The Ship Building – was built on the hull of a schooner moored there in 1849. The old shore of the city did indeed wash up on the eastern side of this historic row. While hard to imagine now, a pair of waving lines etched into the street on Hotaling Place, behind Montgomery, mark the line of the old shore.

This illustration of San Francisco in March 1847, before gold was discovered in California, is signed as accurate by military officials. It shows Montgomery Street on the shore of the bay.

Archival

Thousands of men with the glint of gold in their eye abandoned their boats here to head to the Sierra, or instead to the distractions and vice of the Barbary Coast. The builders of the new city used the detritus and abandoned hulls as landfill to build on, eventually turning the little fishing village into a city. According to the National Register of Historic Places, the ship that 716 Montgomery was built on was likely named The Georgian.

After housing a plumber’s shop, clothing store and printer’s press, in 1930, famed artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera made the building their studio. Over their 10 years there, the married couple became stars, in the art world at least. Rivera painted three murals across the city. And while some in City Hall were outraged at commissioning a card-carrying communist to decorate the city, other artists were honored to have him. “I believe he is the greatest living artist in the world and we would do well to have an example of his work in a public building in San Francisco,” said San Francisco artist Maynard Dixon at the time.

Artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, in San Francisco, Dec. 5, 1940.

Image via SF Public Library

Rivera’s three frescos in the city include the famous “Allegory of San Francisco,” still looking over the staircase in The City Club on Sansome Street today.

This story has been updated.