The first time I tried to use a tampon, it didn’t work. It was the summer of 1998. Saving Private Ryan was dominating the box office and I was dealing with my own bloody mess: my first-ever period. I remember the swelling panic as I read the Tampax insert about toxic shock syndrome. I remember trying out the suggested poses: seated on the toilet? Standing with one foot on the bathroom counter? No matter how I arranged myself, when I put the tampon where it was supposed to go it felt like trying to poke through a tambourine. There was no pain, but it wouldn’t go in. I remember wondering if maybe I just didn’t have a vagina at all.

Advertisement

I told my mom what had happened. A day later, a tube of K-Y Jelly appeared on the bathroom counter. It didn’t help, but it did make my hands goopy. I used pads instead.

Advertisement

Advertisement

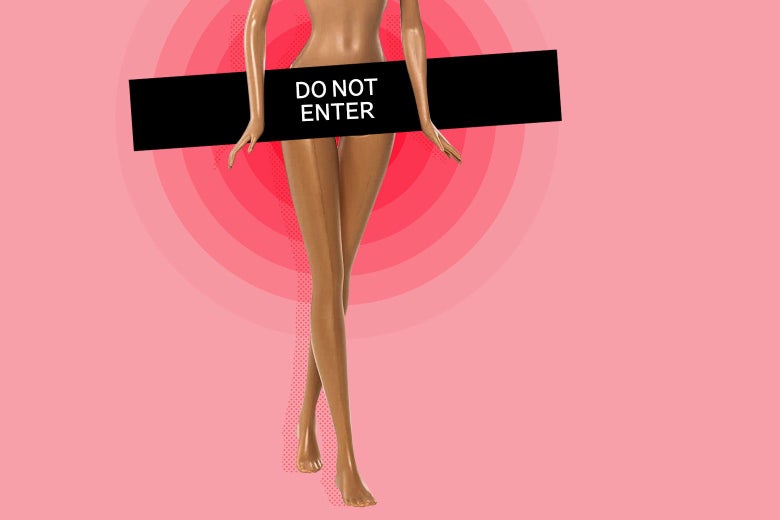

When I decided to have sex for the first time, with a boyfriend in college, things went similarly: I felt a dull pushing sensation around my general vaginal area, and significant embarrassment for everyone involved. I was prepared to expect pain and bleeding while losing my virginity; the possibility had been communicated to me at age 12 by a surprisingly knowledgeable fellow nerd at summer camp. I didn’t know what to make of the fact that I seemed to have Barbie-doll anatomy. After a few more tries over a couple of weeks, we pried things open enough to achieve intercourse. It felt to me like he must have wrapped his penis in sandpaper.

Advertisement

I went to the college OB-GYN to ask about it. She knew me well by then—until she’d finally put me on hormonal birth control, I’d been in her office every month looking for relief from the extreme cramping and gastrointestinal issues that came with my periods. This time, she performed a pelvic exam and told me that she could tell the entrance to my vagina was “angry.” She suggested Calendula Cream to soothe the inflamed entrance to my vagina. It gave me an itchy rash that I never followed up about. Nothing got better: The few times I tried penetrative sex after that were painful, and I’d find blood in my urine for days afterward. Eventually I quit trying.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Something I wouldn’t know for more than a decade: Pain during penetration isn’t normal, but it’s common. Researchers think vestibulodynia—a mouthful of a word for pain that occurs at the small ring of tissue at the entrance of the vagina—might affect as many as 1 in 6 people of reproductive age with vaginas. This can occur alongside vaginismus, pain deeper in the vaginal canal caused by involuntary muscle spasms and pelvic floor muscles that have too much muscle tone. People with these conditions don’t need a flower-power cream, or to be asked, “Have you tried foreplay and lube?”—a refrain I would hear from many doctors over the years.

While there’s no consensus on how to treat vaginal pain that occurs during sex, the current research indicates that a combination of physical therapy, sex therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and medical management leads to the most significant and longest-lasting relief. Over the next 17 years, I’d take a tour through most of them. Most recently, I wrapped up participation in an ongoing study by researchers at University of California–Los Angeles and Duke who are learning more about how this pain condition works, and which medical interventions help which patients. But it would take a lot of bad sex before I even got a diagnosis. I felt, for a long time, like my vagina had some kind of curse.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The dilators were a set of smooth, bullet-shaped silicone … well, dildos.

If the whole vestibulodynia thing is news to you, especially for something so widespread, well, your doctor might not know much about it, either. Haley Cutting, a UCLA-based physician’s assistant and research clinician for the study, says these conditions are poorly understood—“and when I say it’s poorly understood, I mean even in the medical community it’s poorly understood.” She recalls seeing one slide on vulvodynia as part of one lecture on overall pelvic pain conditions in med school; it “barely registered on my radar” prior to her involvement with the pain study. A primer on vulvodynia published last year in Nature Reviews notes that this is “not surprising,” because chronic pain and sexual health are “two health areas that have been generally neglected in graduate training programmes worldwide” and that “tend to make most health-care professionals uncomfortable.”

Advertisement

For years, it made me uncomfortable to talk about, too. After college, I began seeing someone seriously in D.C., where I’d moved after graduation. After a month or two of dating, I sensed P-in-V attempts in our future. It took a lot of alcohol—enough that I don’t completely remember the conversation—before I tearfully confessed one night that I was not very good in bed because I found penises painful. We didn’t talk about it again. Over the course of our two years together, I found satisfaction in kissing and cuddling; he found satisfaction in cheating on me a lot. When we broke up, I decided it was time to look for the person of my dreams—a doctor who could tell me what was wrong.

Advertisement

Advertisement

I expected to be single for a while—yearslong dry spells had been my norm between relationships—and I was determined to use this time to get the better of my vaginal pain. Also, I wanted to use tampons like my friends did. I made an appointment with a new doctor, a kindly older man with an oracular streak—during the pelvic exam I mentioned I wasn’t dating anyone and was considering going off birth control. “Oh, I think you’ll have found someone special by the time you’re in here next year,” he replied, gazing into my vagina as though it were a crystal ball.

Together we decided that I would stop the hormonal birth control, since in some cases it could dampen desire and arousal, leading to painful vaginal dryness. (I’d later learn that overall, the literature does not recommend that patients who experience pain with penetration stop hormonal birth control, though some doctors who specialize in vulvar pain might recommend switching in specific cases after a physical examination and a hormone panel.) He also told me to look up vaginismus and prescribed me a set of vaginal dilators, which I ordered online.

Advertisement

The dilators were a set of smooth, bullet-shaped silicone … well, dildos. They came in varying sizes and were hollow, fitting together like a set of Russian nesting dolls. I was to insert them into my vagina every night, working from smallest to largest and holding each dilator in place for a few minutes in order to stretch and expand my pelvic floor muscles. Because the process is cold and awful, the doctor advised me to “do something relaxing while you’re using them.” I mostly watched Lost on my laptop.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Among experts, dilators are a widely accepted first-line treatment for what’s called “genito-pelvic pain,” a broad catchall category that includes those long V-words: vestibulodynia, pain at the vaginal opening, and vaginismus, pain deeper in the vaginal canal. (These categories are a bit of an oversimplification—bodies are complicated, and medical research on vaginas and vulvas in particular is evolving rapidly.) Physical therapy, which can include dilators, has been shown to significantly improve pain in 71 percent to 80 percent of patients, according to a 2017 metastudy published in Sexual Medicine Reviews. But the recommendation usually isn’t to use dilators on their own and unsupervised but for the cast of a supernatural television show. In fact, any one of the treatments that fall under the physical therapy umbrella—including dilators, manual therapy, and biofeedback—is less effective than a combination of these techniques, especially when paired with cognitive behavioral therapy to address the fear of pain. The idea behind physical therapy isn’t to brute-force things open but to build confidence, reduce fear, and learn to relax the muscles.

Advertisement

If the suggested treatment is a delicate cocktail with varied, balanced flavors, my latest OB-GYN was a sort of gonzo bartender, pouring me a shot of one thing chased with something unrelated. Nonetheless, it helped: Off birth control, I was experiencing sexual desire for, frankly, the first time ever. Eventually, I could use the largest dilator with bearable amounts of pain; I even used a tampon or two. And the OB-GYN’s prediction came true: Within a year I had a new boyfriend.

Advertisement

Maybe it was my nightly close encounters with my vagina, or maybe I was just getting more mature, but I was able to tell the new boyfriend about my pain problem without dying of embarrassment. He in turn did something no boyfriend had done before and asked what did and didn’t feel good to me, a conversation we’d continue as our relationship did. Along with the dilators and the courage, I had learned how to find really good lube (pro tip: product guides in magazines for gay men). If we were quite careful, we could have honest-to-goodness P-in-V s-e-x. Sometimes it was fun. Sometimes, a lot of fun. When we broke up, it wasn’t for reasons related to intimacy.

Advertisement

Before long, I’d relegated the dilators to a box under the bed. I moved to pursue a career in publishing in Brooklyn, where I found a new boyfriend whom I’d eventually marry. We were able to have careful, well-lubed, enjoyable sex. It wasn’t pain-free, but I’d learned how to talk about what hurt … and what felt good.

I imagined these muscles like the spiraling doors of a sci-fi spaceship, closing up tight to deny entry to visitors.

Then, on the advice of my New York OB-GYN—with the move came yet another OB-GYN—I decided to try a low-hormone IUD. I screamed when it went in; it was as much pain as I’ve ever felt. The next morning, I woke up with swollen red patches under my eyes, which my OB-GYN assured me were unrelated. Looking like a sunburned panda wasn’t a good omen, though. The sheer pain of IUD insertion seemed to have shocked my body back into its stressed-out, defensive default. It sparked an association between “penetration” and not just “discomfort” but “danger.” The more I tried to push past that through sheer force of will, to override my muscles and neurons, the stronger the connection got, making sex more and more painful. Soon, the pain of penetration became unbearable—a raw knee scrape being reopened, a Microplane across a knuckle. My partner and I would begin having sex like normal—and then suddenly I’d have to call it quits, sobbing onto his bare shoulders. I’d suggest a new position, we’d give it a try, I’d cry more. I felt broken.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The prospect of a new OB-GYN always gave me hope—maybe a fresh doctor would be the one to fix me. It wasn’t long before I was on the doc market again after moving with my partner to Los Angeles. (We were tired of snow.) The L.A. OB/GYN, like each who’d come before, could find nothing wrong with my vagina. Everything “looked normal.” She did not doubt I was experiencing pain—none of them doubted me—but I was the only one with evidence. My body was not producing receipts.

She hooked me up with a physical therapist who had recently done a certification in vaginismus. Once a week I’d take an extended lunch break from my new office job so I could lie on a table while the physical therapist put her fingers inside me, manipulated my pelvic floor muscles, and told me how much progress I was making as she manually stretched the triangle of pelvic floor muscles that govern penetration. (I imagined these muscles like the spiraling doors of a sci-fi spaceship, closing up tight to deny entry to visitors.) She had me dust off my dilators, and gave me homework: I’d hole up in the bedroom each night, using them from smallest to largest, and perform a series of stretches. I’d text my boyfriend when I was almost done, and then find him waiting outside the bedroom door, arms open to encircle me in a hug.

Advertisement

It seemed like the exercises should have helped, but they didn’t. After the shriek-inducing IUD insertion in New York, I had still desired sex; I just found it painful. After a few weeks of physical therapy and dilators I didn’t even want to try.

I went through cycles—feeling depressed, doing research, finding a promising book to read or sexologist’s advice column to write in to, filling out the book’s worksheets or ignoring the advice of the sexologist who suggested I try anal, feeling more bummed, repeat. We started couples therapy and learned to get creative in the bedroom, which helped make us braver about communicating our feelings and desires but didn’t necessarily affect my own sexual fulfillment. I had learned, in the minor interlude during which I could have careful penetrative sex, that I enjoyed careful penetrative sex, that it didn’t have to be a degrading experience that would leave me bleeding and aching for days. Losing that pleasure to pain—pain that didn’t seem to respond to my diligent efforts to pry it open or massage it loose, that was in fact getting worse the harder I worked to alleviate it—was crushing.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

During one of the “doing research” phases of my sadness loop, I found Andrea Rapkin, a specialist in genito-pelvic pain nearby at UCLA. At that point I knew I had vaginismus, but I’d begun to suspect there was more to my pain than misfiring muscles—why would muscle spasms make me bleed and sting?—and I hoped a specialist might have answers that a generalist OB-GYN would not. I called to make an appointment. “She’s taking new patients, but her earliest appointment is three months away,” the receptionist explained. I’d been living with this for years; I could wait.

In late 2019, I sat at a nurses’ station to complete a long survey about my history of pain. I circled words from a list of adjectives to describe the kinds of pain I associated with different experiences. Menstrual cramps: gnawing, throbbing. Inserting a tampon: rasping, tugging. Penetrative sex: splitting, pinching, stinging, sharp. It was already the most information any OB-GYN had collected about my condition in a decade and a half. By the time I was undressing for the pelvic exam, I was nervous but hopeful.

Advertisement

“I can tell already that this is hormonal, but we’ll do blood tests to be sure,” Rapkin said almost as soon as she began the visual exam. I started crying—I’m crying now, as I write. Finally, a doctor didn’t just believe in my pain. She saw it.

Advertisement

After my bloodwork came back, we met to discuss my diagnosis. Dr. Rapkin’s pelvic exam—which involved a lot of poking and prodding with a cotton swab that my body registered as sharp—had confirmed my existing diagnosis of vaginismus, and she’d noted that the work I’d done with the dilators had been paying off. But my testosterone levels were low—I have the “free T” of someone who’s already gone through menopause, even though I still have periods. (Lucky me.)

Advertisement

Rapkin had seen from the visual exam that my vulva was atrophied—I have thin, crepelike tissue where you’d expect plump and perky—which is a consequence of my not-quite-typical hormones. This thin tissue tears easily, hence the pain and bleeding. (My body also doesn’t self-lubricate well, which doesn’t help.) Vulvar atrophy is only apparent if you’re looking for it. Rapkin was the first doctor to see it in me because she was the first doctor who knew how to look.

In addition to vaginismus, which I was already healing through physical therapy, I received a diagnosis of vestibulodynia—specifically provoked vestibulodynia, which means I only experience pain when something actively touches the vaginal entrance. Dr. Rapkin prescribed a hormone cream for me to apply to the painful vestibular region once a day. Within a week I had noticed a significant change—healthy discharge, reduced pain, significantly increased desire to get busy with my partner. I could even use tampons.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

I don’t know, I might never know, why this pain came for me. Haley Cutting—the clinician for the vestibulodynia study—explains that researchers have identified any number of triggers for the condition, but “there’s not a cohesive one.” Birth control (like the pills I’d taken through my 20s), yeast infections and vaginal infections (check), trauma (negative), childbirth (nope)—all are potentially associated with vestibulodynia. But more research is needed; associations can serve as helpful clues pointing clinicians toward possible diagnoses, but they are not necessarily causes.

It was an easy decision to take part in the UCLA-Duke study, for which Rapkin is one of the lead researchers. For several months I used a cream (or a placebo) and took a pill (or a placebo), filled out surveys, and was poked and prodded with instruments ranging from mundane cotton swabs and blood-draw needles to high-tech pressure sensors. My part was over in six months, but the study will run for four years and the researchers are hoping to enroll 400 participants by the time it concludes; its results will be published for medical professionals and will hopefully give clinicians more information about how people with VBD respond to medical treatments.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Even without the study, I know what makes my pain worse: ignoring it, attempting to muscle through it or walk it off. And I’m still learning about what helps. A hormone compound seems to help restore the thinning vulvar tissue that contributes to the vestibular pain. Physical therapy seems to help my hypervigilant pelvic floor muscles relax. Couples therapy helps me talk to my partner about our boundaries and our desires. Learning more about these conditions and participating in efforts to further the science helps me feel less isolated. I’ve never met someone else with this condition—at least not that I know of—but I’ve learned I’m not alone. It’s a relief.