From social work to astronomy to the law, these leaders are pushing scientific and scholarly boundaries—and lifting up the next generation of Latinx academics

According to data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics, Latinx academics account for roughly 6 percent of full-time higher education faculty—despite being the second largest racial or ethnic group in the United States. A study from the Hispanic Journal of Law and Policy points to institutions’ lack of commitment to diversity, issues surrounding recruiting and hiring, and insufficient social and emotional support as some drivers of this gap.

And yet, as multiple papers and studies have shown, diversity has positive outcomes for both the quality of research and for the education of students from all backgrounds. At Boston University, Latinx professors are making a difference on campus and in the world—leading research that impacts the Latinx community and helping mentor the next generation of researchers and academics.

This National Hispanic Heritage Month, The Brink is celebrating their work—while also using their stories and advocacy to highlight issues shaping the Latinx community. Here, we recognize just some of the accomplished Latinx researchers on our campuses.

A quick note on terminology: National Hispanic Heritage Month is the official name of the monthlong celebration of the culture and influence of people of Latin American descent in the United States. However, people who fall under that category have different terms they identify with, based on personal preference. In this article, the terms Hispanic, Latinx, Latino, and Latina are used interchangeably, based on the terms used by interviewees.

Hugo Javier Aparicio: Investigating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare

“As a Hispanic, first-generation immigrant, my career path has been most heavily influenced by my parents,” says Hugo Javier Aparicio, a neurologist who studies the risk factors for conditions and diseases of the brain, specifically stroke and dementia, with the goal of better predicting and preventing them. For many years, Aparicio’s mother was the only Spanish-speaking family therapist in his home state of Kentucky. “She cared for essentially all of the recent Hispanic immigrants in our part of the state,” says Aparicio, a BU Aram V. Chobanian & Edward Avedisian School of Medicine assistant professor of neurology. It gave him an early awareness of health disparities.

Aparicio’s research tries to understand how diseases of the brain impact people of color, individuals of different ethnicities and cultures, or people of different sex and genders. “I am motivated by the concern that once these brain diseases develop, it is often too late to effectively treat [them], so our efforts to promote personalized preventive interventions for these conditions can [have a large] impact on the brain health of our patients,” he says.

He hopes to see more researchers and professors of different backgrounds join this effort. “Diverse researchers and professors have been shown to engage in research that is more specifically directed toward, and aligned with, the interests and needs of the communities they come from,” says Aparicio. “Understanding the cultures, and in our case as Spanish-speakers, being able to speak the language, is a major first step toward ensuring that research participants are representative of the population.”

Diana M. Ceballos: Inspiring the Next Generation of Public Health Leaders

Diana M. Ceballos has dedicated her career to addressing health disparities by identifying the environmental factors that cause disease, injury, or impairment. She hopes to better understand the health effects from exposure to toxins and address the disproportionate burden of risk in vulnerable populations.

For Ceballos, a School of Public Health assistant professor of environmental health, the work feels personal. “When I see people suffering that look like they could have been my grandmother, my cousin, or my relatives, it touches me deeply and calls me to action,” she says. “Especially when their suffering is related to the structural racism that creates an unequal burden of exposure and health outcomes within these communities, and I see solutions are possible but do not exist.”

In her lab, Ceballos is mentoring students with similar passions. “Many immigrants and minority students naturally reach out to work in my lab or take my classes, because they resonate with the projects and the populations served by my research, or the topics covered in my teaching,” Ceballos says. “It has been a privilege to inspire and guide Latinx students to be the next public health leaders, while providing them with the opportunity to learn strong science with a community-engaged approach that allows researchers to respond to the realities of these communities.”

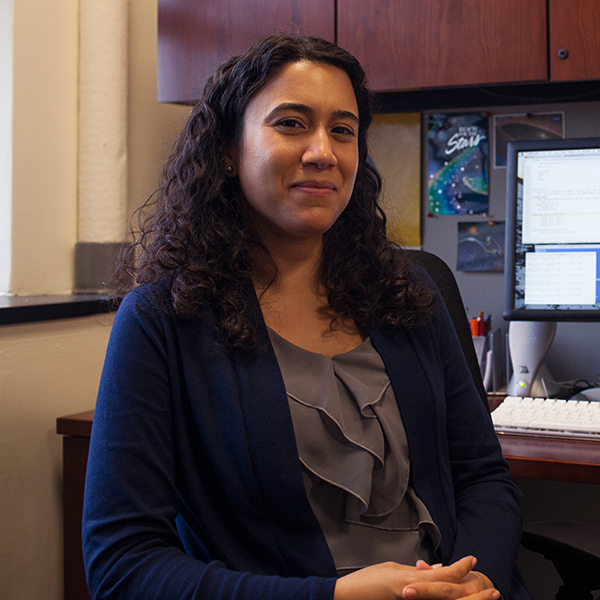

Catherine Espaillat: Building a Supportive Community “Where Black, Indigenous, and/or Latinx Women Belong and Can Shine”

Catherine Espaillat, a BU College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of astronomy, studies how young stars and planets form out of protoplanetary disks. Before coming to BU in 2013, she was a National Science Foundation Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellow and a NASA Carl Sagan Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

On top of her teaching, research, and service, Espaillat is also passionate about mentoring young astronomers underrepresented in STEM fields. “Many Black, Indigenous, and/or Latinx women experience isolation due to our minoritized status in academic spaces,” Espaillat says. To address this, she founded the League of Underrepresented Minoritized Astronomers (LUMA) in 2015. LUMA is a peer mentoring community for graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, faculty, or research scientists in physics, astronomy, and planetary science. “LUMA’s goal is to provide a safe, supportive virtual community where Black, Indigenous, and/or Latinx women belong and can shine,” Espaillat says.

Raul Garcia: An End to Oral Health Disparities

At the BU Center for Research to Evaluate and Eliminate Dental Disparities, Raul Garcia, a BU Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine professor and chair of health policy and health services research, wants to make sure everyone has access to the same level of oral healthcare. Garcia’s work is largely directed to lifting up the health of underserved populations, such as elders, minorities, and people with disabilities.

He says his cultural identity and lived experience as a Latino in the United States have had a fundamental impact on his research into the nature of oral health disparities—and on identifying ways to eliminate them. “Among the major US racial and ethnic minority groups, Latinos tend to bear the greatest burden of oral disease,” he says. Garcia was the first dentist to be appointed to the Advisory Committee on Minority Health, a national group that advises the US Department of Health & Human Services, and is helping to support those following in his footsteps as a mentor on the NIH-supported MIND the Future program, which aims to enhance the diversity of the dental research workforce. He’s also a member of the National Advisory Dental and Craniofacial Research Council of the National Institutes of Health, developing programs to promote the entry and retention of Latinos, and other underrepresented minorities, in dental research careers.

Jasmine Gonzales Rose: Reforming the Law to Fight Discrimination

Jasmine Gonzales Rose says her experiences as a Latina are a driving force in her career. “The racial and class discrimination I experienced as a young person prompted me to become a lawyer,” says Gonzales Rose, a BU School of Law professor, “and the absence of diverse voices I observed in legal scholarship inspired me to become an academic.”

Now, she’s a leading voice on evidence law and race and language, and chair of policy at the BU Center for Antiracist Research. Gonzales Rose’s current focus is the issue of evidence raised by racialized police violence and linguicism—discrimination based on how a person speaks or uses language.

“Often, Latino/a/x/es and other people of color misperceived to be foreign are subject to linguistic discrimination directly or as a proxy for race discrimination,” Gonzales Rose says. “While the law has been reformed to not allow discrimination on the basis of looking like a person of color, it too often allows discrimination on the basis of sounding like a person of color—and that’s a problem.”

Gonzales Rose is the first-ever tenured Latinx professor at the BU School of Law. While proud of this trailblazing distinction, she hopes to one day be one of several. “If we are going to properly prepare our students to be effective leaders, policy-changers, and innovators, we need our faculties to represent all communities,” she says. “No matter what their background, students need diverse teachers, mentors, and examples.”

Daniel Jacobson López: Raising Awareness “about the Struggles and the Beauty of Gay Latino and Black Men”

Daniel Jacobson López, a BU School of Social Work assistant professor, knows that research can be personal, as well as professional. “I do not have the privilege to experience the world without personally contending with racism, homophobia, and/or anti-Semitism,” he says.

López, an expert on trauma, researches how having multiple marginalized identities impacts services offered to gay Latino and Black men who are survivors of sexual assault, as well as violence against members of the LGBTQ+ community.

“The goal with my research is to help others know that they are not alone and find the peace they deserve,” he says. “And, secondly, to help raise awareness about the struggles and the beauty of gay Latino and Black men.”

Through his work on SSW’s equity and inclusion committee and as cochair of the school’s emerging scholars program, López is working to help increase the diversity of academics and social workers. “When there is a lack of Latinx therapists and social workers, communities suffer due to language barriers and a lack of culturally responsive therapists,” says López. “Additionally, Latinx students need to have professors who are Latinx to give them hope that they can be anything they want to be, and to let them know that they belong in these spaces.”

Maria C. Olivares: Sustainable Social Change

Maria C. Olivares, a BU Wheelock College of Education & Human Development research assistant professor, is researching and designing innovative learning environments and organizational structures that nurture learning and growth for underrepresented students in STEM.

Originally from South Central Los Angeles, Olivares is the daughter of Mexican immigrants. “To this day, my parents continue to work six days a week sourcing, procuring, prepping, and selling extraordinarily delicious street food, despite ailments that come with growing older,” says Olivares, who is also part of the BU Earl Center for Learning and Innovation. Their struggles have “been an endless source of both pain and motivation as I strive to honor their labor and life of service and sacrifice.”

At the Earl Center, Olivares works with students, educators, and researchers to create learning environments that foster impactful and expansive STEM education. She’s currently coleading several community-based research projects with funding from the National Science Foundation and the Spencer Foundation, including one that aims to create informal STEM learning opportunities for hospitalized pediatric patients, especially youth of color from low-income backgrounds.

It’s work she continues to trace back to her parents and their efforts to help her pursue educational opportunities that they never had access to. “Who they are, who I am, and where I come from ground my work and orientation to research and design as service,” Olivares says. “I tell anyone who will listen that my time here has to be worth it. For me, that means designing sustainable social change.”